Calculating Free Cash Flow: 5 Illustrated Examples From Actual 10-Ks

Some readers have emailed me with questions about exactly how to calculate free cash flow, including: Do you include changes in working capital? Do you really have to use SEC reports instead of finance websites?

Yes. You really do have to use EDGAR. Finance sites can’t parse a free cash flow statement the way a trained human like you can. As you know, I’m not a big believer in abstract theories. I think you learn by doing. By working on problems. By looking at examples.

Here are 5 examples of real cash flow statements taken from EDGAR.

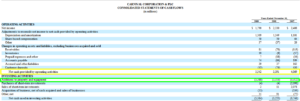

We start with Carnival (NYSE:CCL).

Notice the simplicity of this cash flow statement. It starts with “net income” (top of page) and then adjusts that number to get to the “net cash provided by operating activities” (yellow). To calculate free cash flow in this case you just take “net cash provided by operating activities” (yellow) and subtract “additions to property and equipment” (green). The result is free cash flow.

As you can see, Carnival produces very little free cash flow. Free cash flow is always lower than net income. That’s because cruise lines are asset heavy businesses like railroads. They have to spend a lot of cash to grow. Carnival’s reported earnings tend to overstate the amount of cash owners could actually withdraw from the business in any one year.

Carnival is our example of a “typical” cash flow statement. There’s really no such thing. But this one is simple in the sense that you only have to subtract one line “additions to property and equipment” from “net cash provided by operating activities” to get Carnival’s free cash flow.

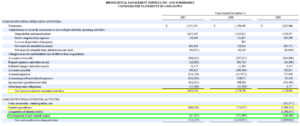

Next up is Birner Dental Management Services (OTC:BDMS).

Notice how Birner separates capital spending into two lines called “capital expenditures” and “development of new dental centers”. This is unusual. And it is not required under GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles). However, it’s very helpful in figuring out maintenance capital spending. If you believe the existing dentist offices will maintain or grow revenues over the years, you only need to subtract the “capital expenditures” line from “net cash provided by operating activities.” But remember, any cash Birner uses to develop new dental centers is cash they can’t use to pay dividends and buy back stock.

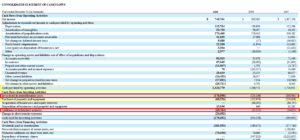

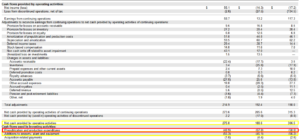

Now for two cash flow statements from the same industry. Here’s McGraw-Hill (MHP) and Scholastic (NASDAQ:SCHL).

These are both publishers. And like most publishers they include a line called “prepublication and production expenditures” or “investment in prepublication cost”. Despite the fact that these expenses aren’t called “capital expenditures”, you absolutely must deduct them from operating cash flow to get your free cash flow number. In fact, these are really cash operating expenses.

These are both publishers. And like most publishers they include a line called “prepublication and production expenditures” or “investment in prepublication cost”. Despite the fact that these expenses aren’t called “capital expenditures”, you absolutely must deduct them from operating cash flow to get your free cash flow number. In fact, these are really cash operating expenses.

For investors, this kind of spending isn’t discretionary at all. It’s part of the day-to-day business of publishing. I reduce operating cash flow by the amounts shown here. At the very least, …

Read more