OTC Markets Group (OTCM): A Far Above Average Quality Company at a Fair Enough Price

Member Write-up by PHILIP HUTCHINSON

| Company | EV / Sales |

| LSE | 8.5x |

| Deutsche Borse | 8.3x |

| Euronext | 7.3x |

| BME | 6.2x |

| CBOE | 10.9x |

| ICE | 8.1x |

| OTCM | 5.7x |

Overview

Many of you will be familiar with the concept of over-the-counter (“OTC”) stocks. OTC Markets Group is the owner and operator of the largest markets for OTC stocks in the U.S. The company trades on its own OTC market under the ticker “OTCM”. You can find its financial releases, earnings call transcripts and other disclosures at the following link:

https://www.otcmarkets.com/about/investor-relations

And for purposes of full disclosure, OTCM is a stock that Andrew and Geoff hold in the managed accounts they run. The analysis here is, however, entirely my own. It’s not Geoff’s thoughts on the company.

OTCM was originally founded in 1913 and has, for many decades, published the prices of “pink sheet” OTC stocks. It has been run by its current CEO, Cromwell Coulson, since a buyout in 1997, under whose management it has digitised its business and standardised the structure of the OTC markets, while still remaining focused on the operation of OTC stock markets in the U.S.

Established stock market operators such as CBOE, NASDAQ, Intercontinental Exchange Group (“ICE”) (the owner of the NYSE), LSE, Deutsche Börse and Euronext, are all fantastic companies. However, they are in many cases much more diversified than OTCM. Take the LSE. It is undoubtedly a great business. However, it is also very diversified geographically and by business line. It owns the London Stock Exchange and Borsa Italiana. But, it also has a big business in clearing of other financial instruments, as well as owning the “Russell” and “FTSE” series of indices. It is today a much broader business than just a stock exchange.

The exchanges listed above are all good businesses. In OTC Markets, however, you can find a lot of the same financial and economic characteristics, but in a much smaller, more illiquid, more focused company, run by a CEO who is also by far the largest shareholder in the company.

OTCM originally used to simply publish prices of OTC stocks in a paper “pink sheet” publication distributed in a manner similar to old style Moody’s manuals. Under Coulson’s leadership, the company has overhauled its business, creating tiered markets for OTC stocks, with three different designations – the highest quality, most stringent, OTCQX market, the OTCQB “venture” market, and finally the pink sheets for all other OTC stocks. OTCM earns subscription revenues from all companies on the OTCQX and OTCQB markets, but not from any stocks on the pink sheets. It has turned itself from a publisher of stock prices to a standard setter, aggregator, and provider of data and trading services that is the owner of the leading OTC stock market in North America.

Unlike the competitors listed above, OTCM is not, technically, a stock market. The precise distinction between an OTC stock and a listed stock, and between the nature of the OTC market (which is not, properly, a stock exchange) as compared to a true stock exchange such as the NYSE or the NASDAQ probably doesn’t matter much from an investment perspective. But, basically, the difference is that OTCM does not operate an exchange on which trades on its markets take place. Trades take place directly between brokers. However, it does publish standards, provide quotes and electronic messaging to brokers, and maintain established and standardised markets.

Economically, this distinction does not matter much. OTCM performs largely the same economic functions as established true stock markets – it is a central marketplace, publisher of standardised information, and standard-setter and compiler of defined stock market lists. Nonetheless, knowing that OTCM is not, technically, a stock market is important in understanding its competitive position.

OTCM earns revenue in three ways. First, it earns fees from brokers who want to trade in OTC stocks. This used to be, by far, the biggest contributor to OTCM’s sales. Fees are earned from brokers on a subscription-per-broker basis, not a transaction fee basis. So, revenues are not (at least, not directly) tied to market volumes or transaction value. Customer retention in this segment is very high. Brokers maintain their subscriptions for so long as they want to trade OTC stocks. However, significant consolidation in the broking industry has led to pressure on this segment’s revenue.

Secondly, OTCM earns revenue from licensing its data on OTC stocks to data providers and users of financial data. A lot of the revenue here comes from large aggregators of financial data – companies such as Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters. This has been a big source of growth over the last decade – licensing revenues having grown from around $5m to around $22m per year over this period. Again, customer relationships are on a subscription basis, although there is meaningful customer concentration in this segment of OTCM’s business and, of course, OTCM is much smaller than its data licensing customers.

Finally, OTCM earns fees from companies who want to be on its OTCQX and OTCQB markets (and also meet the qualifying criteria for financial standing, timeliness of filings, etc.). (Companies who do not qualify may well still be listed as OTC pink sheet stocks, but they do not pay for this, so there is no direct revenue for “pink sheet” stocks to OTCM.) There are two sources of fee here – initial fees paid by companies when they join the OTCQX or OTCQB markets, and then recurring annual fees thereafter. This has been a really key source of growth. This segment has grown from less than 10% of revenues in 2005 to now, in 2017, being the biggest contributor to the company’s revenue. Customer retention and earnings quality are high as companies pay a yearly subscription in advance for as long as they remain on the market – and the cost is not huge from the customer’s perspective.

Durability

Although it is a relatively small company, OTCM has a long history. As noted above, its heritage as the publisher of pink sheets stock prices dates back to the early 1900s. So, history tells us that the business has been durable (albeit possibly sub-scale) in the past.

If we disregard the technical difference that OTCM is not a proper stock market, durability appears even greater. The LSE, for example, was founded in 1571, the New York Stock Exchange in 1792, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in 1605, the Borsa Italiana (the Italian stock exchange, now owned by the LSE) in 1808, and the Irish Stock Exchange (now owned by Euronext) in 1793. So, stock markets have very, very lengthy heritage as durable businesses. They are some of the oldest businesses around.

This makes sense. The functions performed by stock markets – pooling capital to fund business ventures – is one of the absolutely fundamental building blocks of a capitalist economy. The need for centralised organisations for the pooling of funds and the trading and standardising of markets in stocks, bonds, etc., is probably one of the most durable business functions it is possible to imagine. It is possible that some of the trading functions performed by stock markets could be rendered obsolete by things like distributed ledgers. However, the truth is that trading functions are only a part of what a modern stock market does. Even if blockchain technology changes how trades are done, it is likely that this will be adopted by the exchanges, rather than displacing them. This is because the exchanges go far beyond trade execution. They also set and enforce rules and standards and publish indices and other market information. This is equally true of OTCM as it is of bigger, better known exchanges.

So, the durability of exchanges themselves appears unusually high.

Of course, as noted above, OTCM is not, technically, a stock exchange. And in addition, many companies whose stock is on one of OTCM’s markets do not file with the SEC. So, there is a risk to OTCM’s durability that its peers do not face: regulation. Could a change in regulation (for example, severe restrictions on the ownership and trading of stock in companies that do not file with the SEC, or perhaps more realistically, deregulation so that listing on the big established markets becomes much easier and cheaper) seriously damage OTCM’s business?

Theoretically, this has to be a possibility. However, the tradition of OTC stocks appears well ingrained in the U.S. If anything, recent regulatory developments appear more supportive of OTCM’s business than the opposite (although of course that is merely a recent trend). And supporting the business of a responsible operator such as OTCM is probably a more attractive proposition for regulators than banning or further regulating and restricting the trading of OTC stocks.

Moat

OTC Markets has a deep moat around its business. It is no different than other stock markets (and, indeed, other marketplace businesses) in that regard. Now, it’s important to understand the extent of this moat. OTCM is a niche business. Its niche is to operate a market for non-listed stocks in the US. It would have no moat to the extent that it tried to expand its business to also operate a market of fully listed stocks.

An understanding of the role of a stock market makes clear why this should be. Although true stock markets such as the LSE or NYSE are trading venues (and, technically, OTCM is not) this is really a technical issue. It’s not what the real key function of a stock market is. Their key function is to provide transparency, tradeability, liquidity, and pooling of capital by setting and maintaining common standards for stocks to adhere to. And the tendency towards centralisation and consolidation is clear. For example, in the UK there were once stock exchanges (and, indeed, exchanges for other assets) in Manchester and Liverpool as well as in London (although they were in fact northern branches of the LSE) but they closed as finance centralised in London. In Spain, there are four stock exchanges (Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao and Valencia) but they are all operated by Bolsa y Mercados Españoles, and in any case the Madrid market is clearly dominant. In the U.S., of course, the NASDAQ and NYSE are competitors. But the reality is that, once a company is listed on one or the other market, it’s rare for it to switch. Customer relationships can go on for many, many decades.

So, exchanges have a clear moat around their existing customers, and there is clear economic benefit to exchange participants (both traders/investors and listed companies) for there to be fewer, rather than more, exchanges. It is, of course, quite different when it comes to competition for new customers (in the form of IPOs and, more rarely, companies switching their listing / trading from one market to another). There is significant competition for this business. A good illustration of this was the IPO of Manchester United (the UK soccer club) a few years ago. Obviously, it’s a UK-based company. But it chose (for whatever reason – likely, in my view, to be related to the valuations afforded to sports franchises in the U.S. compared to the UK) to list on the NYSE rather than the LSE. When it comes to competing for new business, OTCM obviously competes with the significantly larger and more prestigious NYSE and NASDAQ. But, it also competes with markets outside the US – in particular, the Alternative Investment Market (“AIM”) owned by the LSE, and the Venture exchange of the Toronto Stock Exchange. AIM is very similar to the OTC Market. Although it is an exchange, it’s a less regulated market for smaller companies, with lower disclosure standards and a “self-policing” regulatory regime where “NOMADs” (Nominated Advisors) – professional advisers retained by the company whose shares are listed – ensure and certify compliance with the AIM rules. Indeed, OTCM’s OTCQX and OTCQB markets are explicitly modelled on AIM – they are a copy of the AIM structure. And then, there are a lot of Canadian junior resources companies on OTCM’s markets. They could clearly choose to list on the TSE.

OTCM claim that being a member of one of their markets is overall a cheaper option for a public company than listing on their competitors’ exchanges. It’s difficult to find definitive information on this. In terms of the fees payable directly to OTCM – it’s reasonably clear that they are a cheaper option than the NYSE or NASDAQ. Whether they are cheaper on an “all in” basis, is harder to determine. That’s because, to be a member of OTCM’s OTCQX or OTCQB markets, a “DAD” or “PAL” must be retained (an independent adviser similar to a NOMAD on the LSE’s AIM). That can be expensive. On the other hand, a company can trade on OTCM’s markets – including its flagship OTCQX market – without filing with the SEC and without incurring certain other compliance costs (e.g. Sarbanes-Oxley). That’s not possible in the case of the NASDAQ or NYSE. OTCM’s own marketing material contains a quote from one of its customers which claims that this has saved them $15m over a number of years in saved compliance costs that would otherwise have been incurred. Of course, that’s marketing. It’s clear there is a big saving for some customers, though. OTCM has a lot of large, blue chip non-US stocks trading on its markets to give better access to US investors – companies like Imperial Brands plc, Roche, and Ferguson plc. These companies are fully listed in their home jurisdictions. If they want their shares to also trade in the US but do not want to file with the SEC – then OTCM is their only option.

The lack of a requirement to file with the SEC is less relevant when it comes to competing against international competitors such as the TSE or LSE, as it is not a requirement of those markets that a company file with the SEC. However, in practice, OTCM offers something that neither of those competitors can ever offer – access to U.S. capital. Realistically, the LSE can’t compete in a major way for U.S. OTC stocks. Nor can it compete for the listing of non-U.S. companies who want their shares to trade in the U.S. as well as their home market. That’s because the investor base for LSE/AIM stocks is predominantly (and in the case of AIM, overwhelmingly) British capital. It’s true there are non-UK headquartered stocks on AIM, but they’re not generally American, and they don’t have a good track record (this should be obvious – a non-UK stock listing on the UK’s least regulated market is an obvious candidate to be fraudulent, promotional, or otherwise subject to capture by insiders).

So, OTCM has a deep moat by virtue of owning the only meaningful OTC market in the U.S. in an industry that tends towards consolidation rather than competition.

Quality

OTCM’s business quality is very, very high. All three of its business segments are subscription based businesses with high customer retention. For example, subscriptions in the corporate services segment are paid in advance year after year for as long as the customer is listed on its market and if the customer doesn’t pay, it’ll lose its listing. And OTCM has very little requirement for tangible assets. It should be able to grow while not having to make any meaningful additional investment in tangible assets.

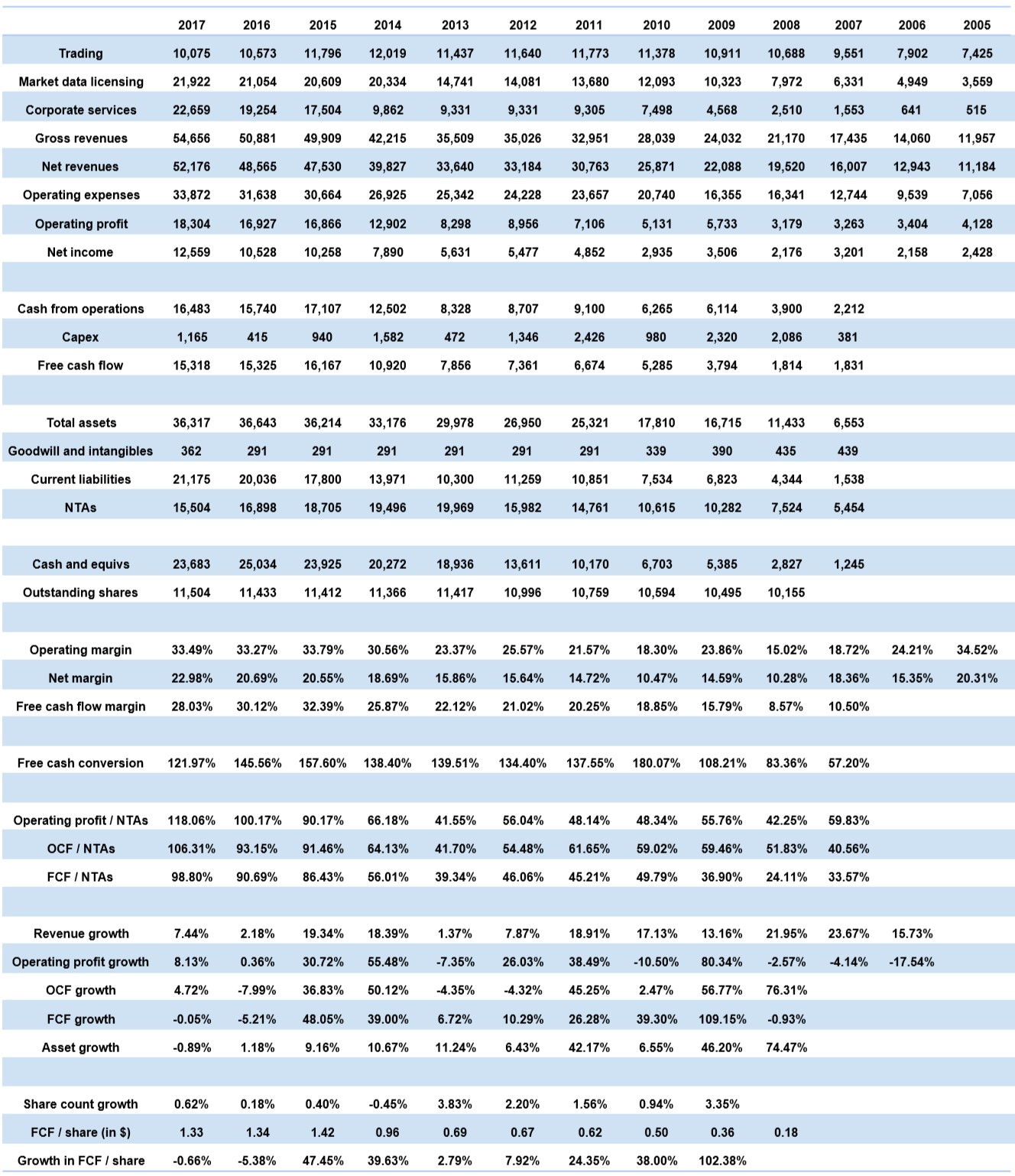

So, you’d expect a business like OTCM – which is, essentially, a subscription based information business – to have very high margins and high returns on capital. And that turns out to be the case. OTCM’s financial metrics have improved over the last decade, which I think is simply the result of increased scale as revenue has grown on a relatively fixed cost base. But in recent years, it’s had a free cash flow margin of around 30%. 30 cents on every dollar of revenue turns into free, distributable cash. That’s with a tax rate of nearly 40%. And tangible assets are minimal. OTCM’s business economics are up there with some of the very best businesses in the world. I usually use something like Moody’s or Facebook as a barometer of a truly extreme high quality business. Well, OTCM has business economics that rival those companies.

The key variables here are whether OTCM’s customer base is stable enough and whether OTCM can add to that customer base, not business quality. It’s absolutely clear that OTCM has very high business quality.

Capital Allocation

OTCM is approximately 30% owned by its CEO, Cromwell Coulson. And it is significantly overcapitalised. It has $25 million of net cash – but it is a highly cash generative company which could clearly carry debt.

Capital allocation is important here because essentially all of OTCM’s earnings come in the form of cash. So, each year management have to decide what to do with essentially 100% of earnings. Now, that’s probably slightly the wrong way to look at things. Because of the nature of OTCM’s business (close to zero requirements for tangible assets), virtually all investment in future growth is expensed – in the form of salaries, marketing, and IT costs. The last decade has seen management focus (successfully) on expansion, building up the OTCQX and OTCQB markets, electronic trading services and the data licensing business. Nor is there any sense in which OTCM is particularly cost-conscious. It appears to be a growth-oriented company. The focus of OTCM’s management, since the MBO led by the current CEO, has been to digitise and modernise the business and invest heavily in the development of the OTCM and OTCQX markets. What they have achieved is very impressive. But nothing I can see suggests that management will do anything other than continue on this path. So, one of the first calls on the company’s cash flow is investment in growth. That doesn’t show up as capex in the financial statements. But it doesn’t make it any less true.

Nonetheless, that leaves a lot of truly discretionary cash flow for management to allocate. As mentioned above, the business is overcapitalised. However, there could be good reason for that. Despite extremely high business quality, there’s an element of cyclicality about OTCM – at least in perception, if not reality. You really would not want a refinancing requirement to coincide with a downturn in the capital markets. So, it could make sense to maintain a cushion of net cash.

As regards what management will do with free cash flow, it’s fairly clear. It will mostly be paid out to shareholders as dividends (there have been some share buybacks too, but largely, it appears, to mitigate stock issuance to employees, and liquidity constraints probably prevent large buybacks). Management have talked about potential acquisitions, but they’ve not actually done one. So, capital allocation appears relatively neutral here. It’s not unorthodox and won’t create substantial value. But, it’s unlikely to be value destructive either.

Growth

OTC Markets is a growth stock. The 12-year compound growth rate in revenue is 13.5%. Over 10 years, it’s 12.1%. And over five years, it’s 9.31%. Clearly, high rates of growth. However, that overall data masks significant variance by revenue stream. For example – over 12 years, revenue from trading services has grown from $7.4m to $10m (and over the last three years, it’s actually declined). Whereas revenue from corporate services (listing fees from companies on OTCM’s markets) has gone from $515 thousand in 2007 to being OTCM’s biggest source of revenue, at $22.7m in 2017.

More recent revenue growth has been mid-single-digit, so it seems imprudent to assume the double-digit rates achieved over the last 12 years. Really, growth (like OTCM’s business as a whole) is going to be tied to OTCM’s ability to protect and grow the number of companies listed on its markets, plus any latent pricing power. It does appear that OTCM has pricing power (it’s put through significant price increases with minimal apparent damage to its business), so we could estimate growth as being:

- Inflation-rate growth (say 3%), in a case where OTCM cannot grow its subscribers at all and merely maintains its pricing power

- Inflation plus GDP growth where OTCM can either increase prices ahead of inflation or maintain prices and grow its subscribers over time (say 5%)

- Nominal GDP growth plus some net subscriber growth of say 2 – 3%, giving 7-8% total.

Now, really, there’s a risk of underestimation here. If you consider that one of OTCM’s closest peers, AIM, has circa 900 companies listed on it (versus circa 1,300 on OTCQX and OTCQB, many of which are non-U.S. companies – there are far more on the pink sheets, but they provide no revenue to OTCM) the opportunity appears significant. Yes, the UK is not an exact parallel of the US, but it’s striking that OTCM’s established markets are not much bigger despite the U.S. economy being obviously much, much larger than the UK. That’s a speculative source of growth. But still, it’s a real possibility.

One thing we can say with certainty is that growth at OTCM is highly valuable. It will cost essentially zero. OTCM saw significant margin expansion from 2007 – 2017. I think it would be unwise to assume any further margin expansion (although it probably isn’t impossible). But OTCM converts anywhere between 25- 32% of sales into free cash flow. So, each dollar of additional revenue is very, very valuable.

Misjudgment

There are two possible ways to be seriously wrong about OTCM. First, does it have a moat? And second, can it grow its business, or is it really just a cyclical company at a good point in its cycle?

One issue I’ve not discussed up to now is that OTCM is an OTC stock that does not file with the SEC. To many people (though possibly not Focused Compounding members) that would be a risk. It’s true that many OTC stocks are risky and potentially have poor corporate governance. But, there’s no direct causal relationship (i.e., OTC stocks are not automatically risky because they are OTC stocks – if anything, it would probably be the reverse). In my view, the corporate governance risk in OTCM is actually much lower than in most companies – including most large, professionally managed, fully listed, SEC-filing companies. First, OTCM’s track record is one of prompt, informative disclosure, consistent cash generation, and dividend payments. Secondly, management (really the CEO) have meaningful ownership in the company. Technically, OTCM is not a founder led business – the Pink Sheets are more than 100 years old – but in terms of the modern business, it might as well be. Thirdly, OTCM has a clear incentive to report promptly and transparently and treat outside investors well, because it is acting as a standard bearer to all the companies listed on its markets. If it practised poor corporate governance, it would harm its own business. So, there are definite risks in OTCM – but corporate governance and management integrity are not things to be concerned with.

The real risks are moat (if OTCM grows, or regulations change, will larger competitors start to outmuscle it?) and quality / growth (is OTCM really a cyclical business in a long up-cycle?). These are real risks – particularly as (see below) OTCM stock is by no means a “value” investment.

The “moat” risk is difficult to quantify. I think that the fact that all stock market owners appear to be high quality, high return, high retention rate businesses, generally tied for historic reasons to specific regions, is a good indication that they all have strong moats, and I tend to think that competition will act more as a limitation on growth than a risk to the existing business. Of course, there are other, harder to quantify risks, such as regulatory change in the US eroding the difference between OTCM and the NYSE and NASDAQ.

The “quality” risk is real. Partly, this is because we don’t have long enough financial records of OTCM’s business in its current form. If we had 30-year records, we could be more confident of OTCM’s quality even in tough environments for the markets it operates. But, the long term record of stock market owners appears to be good – if volatile. There is a clear quotation risk. When we next go through a tough period for capital markets, businesses that are tied to, or serve, the capital markets are likely to suffer disproportionately. Unlike operators of true stock exchanges, OTCM’s revenues are not based on trade volume or trade value, so its business should prove relatively resilient. However, this is not a given. For example, if a large percentage of companies listed on OTCM’s markets are dependent on external finance, or tied to a cyclical end market, there is a risk that a bust affecting those companies will lead to meaningful shrinkage in OTCM’s “installed base” of companies who are listed on its markets. There is some precedent for this if you look at the statistics on the AIM market. That market had a high of 1,694 listings, in 2007. The post-crash era has seen that reduce substantially, and the current number of companies on AIM is 942, around 55% of that 2007 high. AIM is well known as the listing venue for a large number of junior resources companies (which are generally not self-financing and often of low quality). So, that probably explains much of the decline. This risk is one that OTCM also faces. It is by no means exclusively reliant on listings by junior resources companies. For example, it has a lot of high quality secondary listings by non-US blue chips (e.g. Ferguson plc, Imperial Brands plc). And it also has a lot of US regional banks which, again, should be a stable customer base.

Nevertheless, the risk of misdiagnosing this company as a stable grower, when in fact it may be a cyclical, is probably the biggest potential misjudgment in the stock.

Value

How to value OTCM depends critically on the way you view the company. Is it a consistent, predictable company, or not? I think it is (at least averaged out over the years). And I think it should be able to turn each dollar of revenue into roughly 45 – 50 cents of operating cash flow.

OTCM, as an entirely U.S.-based company, is a significant beneficiary of the tax cut. Cash tax paid has been roughly 11 – 12% of revenues over the last three years, or nearly 40% of EBIT. That figure will clearly be lower in future. I would assume a tax rate (for both state and federal tax) of 27%, around one third lower than historically.

So, I estimate OTCM will:

- Convert 45% of sales into operating cash flow;

- Pay tax of 8% of sales; and

- Spend 1% of sales on capex,

Giving a normalised free cash flow margin of 36%. Further, OTCM can distribute 100% of this free cash flow each year while still growing.

To provide a return that matches the market’s 8 – 10% over time, then, OTCM should trade on an EV / Sales multiple (or EV / free cash flow multiple) such that likely growth plus current free cash flow yield equal 8 – 10%.

If we assume that OTCM will grow at 5% – i.e., really no more or less than nominal GDP – then the free cash flow yield should be 5%, or put another way, the EV / Sales should be just over 7 times. Using 2017’s sales of $52m, that gives us a warranted enterprise value of $374m. This might even underprice OTCM, if you believe that the market is currently expensive and priced for single-digit returns over the next decade. (However, there is a problem with that line of thinking. If the market is priced for disappointing returns over the next decade or so, it’s unlikely that OTCM will be enjoying optimal business conditions.)

An EV / Sales ratio of 7x does not seem outlandish on a peer valuation basis, either. It is lower than all of the peers listed at the start of this article.

Not all of these are perfect comparables. And of course, the above might just say that all exchange operators are overvalued. That is certainly plausible given the long bull market we’ve had (in the U.S., at least). But, exchange operators are similar to ratings agencies in terms of their business economics. And work I’ve done looking at Moody’s suggests that it would have needed to trade at over 8x sales in order for its performance to have merely matched the market (rather than beat it). So – long term – it’s likely that the above valuations will not prove excessive.

And, honestly, the growth prospects for OTCM seem better to me than for some of the above stocks – certainly better than the likes of Euronext or the BME. (On the other hand, some of the above companies have a strategic value that OTCM probably doesn’t have. You could easily imagine a takeover of the LSE, for example, at a very, very high price.)

So – based on 2017 revenues, our valuation of OTCM is an EV of $375,662.000.

There are currently 11.6 million outstanding shares, and OTCM has net cash of $25m. Its current EV is $306m (at a price of $29 per share). So, it’s trading at a discount of 19% to my estimate of appraisal value.

A different, and simpler, way to look at this is to say that OTCM is trading at a normalised free cash flow yield (taking into account the effect of the tax cut) of 5%. It can grow free cash flow per share between 3 – 7% a year (taking into account that there will be some dilution from stock issuance to employees). So, it should return anything from 8% at the low end (which I do think is quite conservative) to maybe 12% if it grows at 7% per year.

At its current price level, I therefore think OTCM represents a good opportunity to buy into a very high quality company. But it’s only a good opportunity if you really think that (a) OTCM has a moat, and (b) it will grow at least some. The margin of safety, such as it is, is entirely one of business quality. OTCM is at best averagely priced, taking into account the tax cut. But, it’s an above average (actually, I think far above average) quality company.