How Acquisitions Add Value – Or Don’t

Someone emailed me this question:

How do you think management should analyze acquisition opportunities? For example, how would you like the management of companies you own to think about them and decide to acquire or not (acquire) a company? Because they could, say, value the companies and determine if they are undervalued or overvalued… also they can make the value of them increase by making changes (e.g., such as Murphy did at Capital Cities by significantly increasing the operational efficiency of acquired companies and Buffett did at See’s by exploiting its untapped pricing power) and so on.

It depends on the company and their approach. The best acquisitions are often horizontal mergers where the company (for example, one rolling up smaller businesses in its same industry) acquires companies that have similar distribution channels, customers, suppliers, etc. and may increase market power this way. There are often cost synergies (especially economies of scales in sharing fixed costs across acquired businesses) in this sort of merger. So, a merger might be done at a high price relative to the acquired company’s previous EBITDA, earnings, etc. but at a reasonable price after these synergies are achieved.

The problem with many mergers (including the above) is that the price paid by the acquiring company is often so high that the benefits of the synergies are really being paid to the selling shareholders from the acquired company rather than being captured by the acquirer. For example, I’ve seen cases where a company pays about 12x EBITDA for a business and probably gets the business at about 5x EBITDA after synergies. The selling shareholders are getting 12x EBITDA. The buyers are – if all goes well – getting something purchased at 5x EBITDA which can work if the company uses debt, cash, or overvalued shares to fund the acquisition. If they use undervalued stock, it doesn’t work well.

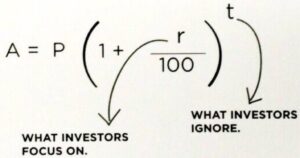

It might seem like this “cost of capital” factor couldn’t be a deal killer when you’re getting something for 5 times EBITDA after synergies. Management might think this too. The synergies here are so huge – an EBITDA margin of 10% pre-acquisition is going to become 25% post-acquisition – that the currency used to do the deal can’t possibly matter enough to ruin the deal, right? Actually, it still can. For example, the acquirer I mentioned that has done deals like this has actually traded in the market at 5 times EBITDA itself at times. So, even deals where it feels 80% certain it can immediately take the EBITDA margin of the target from 10% to 25% don’t actually clear the company’s own opportunity cost hurdle. Its own stock without any added synergies is actually cheaper than buying something with boatloads of synergies.

In such cases, the company would be better buying back its own stock at 5 times EBITDA than buying something and doing all the work of integrating it – and taking on the real risk integration won’t work quite as well as hoped – just …

Read more