Warren Buffett’s Partnership Letters and My Investing Thought Process

“You can’t predict. You can Prepare.”

-Howard Marks

I have been reading all of Warren Buffett’s old partnership letters the past week or so. These letters are the letters he wrote to his Investors yearly (and then semi-annually) from 1957- 1970 before winding down his partnerships to eventually run Berkshire. I was inspired to do so because I have also been rereading The Snowball by Alice Schroeder’s for the past month, and it’s awesome how it takes you back to the beginning and goes year by year in Warren’s life as the snowball was building up and starting to roll downhill. There are a few books I re-read every year, and The Snowball is one of them. (Also on that list is Poor Charlies Almanack, another book I highly recommend.) The partnership letters are too long to embed in this post, but if you go to this link you should be able to pull them yourself:

Although Warren invests completely differently now, there are still a lot of takeaways you can pull for yourself from his writings. One thing I found interesting is on page 20 in his 1961 letter where Warren goes over his different types of Investment Categories. I’ll let him explain:

“The first section consists of generally undervalued securities (hereinafter called “generals”) where we have nothing to say about corporate policies and no timetable as to when the undervaluation may correct itself. Over the years, this has been our largest category of investment, and more money has been made here than in either of the other categories. We usually have fairly large positions (5% to 10% of our total assets) in each of five or six generals, with smaller positions in another ten or fifteen. Sometimes these work out very fast; many times they take years. It is difficult at the time of purchase to know any specific reason why they should appreciate in price. However, because of this lack of glamour or anything pending which might create immediate favorable market action, they are available at very cheap prices. A lot of value can be obtained for the price paid. This substantial excess of value creates a comfortable margin of safety in each transaction. This individual margin of safety, coupled with a diversity of commitments creates a most attractive package of safety and appreciation potential. Over the years our timing of purchases has been considerably better than our timing of sales. We do not go into these generals with the idea of getting the last nickel, but are usually quite content selling out at some intermediate level between our purchase price and what we regard as fair value to a private owner. The generals tend to behave market-wise very much in sympathy with the Dow. Just because something is cheap does not mean it is not going to go down. During abrupt downward movements in the market, this segment may very well go down percentage-wise just as much as the Dow. Over a period of years, I believe the generals will outperform the Dow, and during sharply advancing years like 1961, this is the section of our portfolio that turns in the best results. It is, of course, also the most vulnerable in a declining market.

Our second category consists of “work-outs.” These are securities whose financial results depend on corporate action rather than supply and demand factors created by buyers and sellers of securities. In other words, they are securities with a timetable where we can predict, within reasonable error limits, when we will get how much and what might upset the applecart. Corporate events such as mergers, liquidations, reorganizations, spin-offs, etc., lead to work-outs. An important source in recent years has been sell-outs by oil producers to major integrated oil companies. This category will produce reasonably stable earnings from year to year, to a large extent irrespective of the course of the Dow. Obviously, if we operate throughout a year with a large portion of our portfolio in work-outs, we will look extremely good if it turns out to be a declining year for the Dow or quite bad if it is a strongly advancing year. Over the years, work-outs have provided our second largest category. At any given time, we may be in ten to fifteen of these; some just beginning and others in the late stage of their development. I believe in using borrowed money to offset a portion of our work-out portfolio since there is a high degree of safety in this category in terms of both eventual results and intermediate market behavior. Results, excluding the benefits derived from the use of borrowed money, usually fall in the 10% to 20% range. My self-imposed limit regarding borrowing is 25% of partnership net worth. Oftentimes we owe no money and when we do borrow, it is only as an offset against work-outs.

The final category is “control” situations where we either control the company or take a very large position and attempt to influence policies of the company. Such operations should definitely be measured on the basis of several years. In a given year, they may produce nothing as it is usually to our advantage to have the stock be stagnant market-wise for a long period while we are acquiring it. These situations, too, have relatively little in common with the behavior of the Dow. Sometimes, of course, we buy into a general with the thought in mind that it might develop into a control situation. If the price remains low enough for a long period, this might very well happen. If it moves up before we have a substantial percentage of the company’s stock, we sell at higher levels and complete a successful general operation. We are presently acquiring stock in what may turn out to be control situations several years hence.”

A few quick takeaways

- Even in these different approaches, he always required a margin of safety

- All Value investing works. If you buy a dollar for 50 cents, you can make money. How you get to that dollar for 50 cents may vary

- He owned many different stocks, it wasn’t until a few years later where Charlie Munger influenced Warren on concentrating on only a few of the best companies out there

- Warren was operating in companies that were 1-10 million dollar market caps at the time, which inflation adjusted would be 8 – 81 million dollar market caps in present terms

Although markets are more competitive now and there may not be as much “mouthwatering” opportunities as Warren had as frequently as he did, there are still plenty of ways to invest. My own personal categories are nothing groundbreaking, but I thought I would spend the rest of this post going over how I generally think about my own personal investing categories.

Bucket A: Companies that I describe as being “capital-light compounders”. These companies produce an enormous amount of cashflow, require very little capital to run and have favorable investment opportunities to reinvest their cashflow at a very high rate of return. These are the types of companies that you should buy and forget about for 5-10 years. Companies like Tencent fall into this category.

Bucket B: Well-known companies that often get mispriced due to short term factors or overreactions by the general market. You can make a career out of this bucket, and many have. One of my favorite investing quotes comes from Allan Mecham when he said:

“I think the most important three words in investing may be: I don’t know. Having strong viewpoints on a lot of securities, and acting on them, is a sure-fire way to poor returns in my opinion. In my view, it’s easier to adopt this “I don’t know” ethos by focusing on the business first and valuation second, as opposed to the other way around. I’ve found that when valuation is the overriding driver of interest, I’m prone to get involved in challenging businesses or complicated ideas and liable to confuse a statistically cheap price with a margin of safety”

In this quote, he talks about following good companies that you would like to own in the future, and then being patient enough to wait for the ripe opportunity. My general time frame for this bucket of stocks is usually 2-4 years.

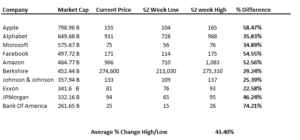

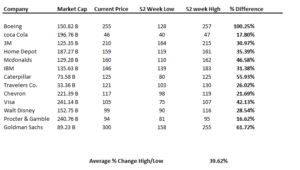

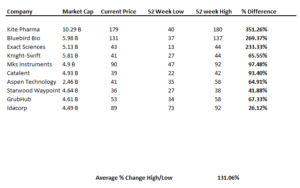

Here are some charts that show how much even very well-known companies fluctuate in any given 52 week period:

I encourage you to run this test yourself and you’ll see that I’m not just cherry-picking companies. Prices move. In Joel Greenblatt’s audited class notes, (probably the absolute best study tool out there, I’ll link below) he talks about price and how it relates to value. He says (I’m paraphrasing from memory)

Look at any 52-week high and low on any stock, why do stocks move around so much? Who knows and who cares, all I know is it happens and will continue to happen, and we should look to take advantage of this.

The point I’m trying to make is that you do not need to find the next 100 bagger investment to make a career for yourself. Although we should never stop searching, there are plenty of other opportunities to find along the way. Because “Bucket A” stocks are so far and few between, when you do find an idea that falls into this category, you must act with conviction and buy up a significant amount. “Bucket A” stocks in my portfolio are typically 15-20% positions, while “Bucket B” are generally 10% positions. I encourage you to start using these filters in your investing process.

One final thought, earlier in the year I attended Charlie Munger’s Daily Journal shareholders meeting in California. It was an awesome experience, and I can’t wait for the upcoming year. I encourage everyone to seriously consider attending. It is more intimate than Berkshire, and is just a room full of 100-200 investing junkies. After the meeting was over, Charlie stayed and answered everyone’s questions for about 2 hours. There is a video of it on YouTube that I will link below. Someone asked him about what he reads and he went on to talk about how he has read Barron’s for 50 years, and out of those 50 years he got 1 idea out of it. So over 25,000+ induvial ideas, and only acting on 1. He invested 10 million in a company and within 2 years it was worth 80 million. He then took this 80 million and gave it to Li Lu to invest which has now grown to over 400 million. The biggest take away from him was his patience. Over 50 years of patience…… But it shows that if you get that 1 big idea right, while also doing well with “Bucket B” stocks along the way, then that is all you will ever need.

Links-

Warren Buffett BPL letters – http://csinvesting.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/complete_buffett_partnership_letters-1957-70_in-sections.pdf

Charlie Munger Q&A video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpzrHPYWojY

Full Daily Journal Video – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAiKQFGS2TM&t=665s

Joel Greenblatt Class Notes – https://www.scribd.com/document/239853147/Complete-Notes-on-Special-Sit-Class-Joel-Greenblatt