United Plantations: A Low-Cost Palm Oil Producer with 11 to 17% Returns on Equity and Excellent Capital Allocation

by WARWICK BAGNALL

United Plantations Berhad (KLSE:UTDPLT, UP for the sake of brevity) is an integrated palm oil plantation, milling and refining company (plus a small coconut plantation). It’s currently too expensive for me to buy but it is a company that I would like to own if the price ever drops to an acceptable level.

Superficially, there are a lot of reasons why palm oil companies look like a bad investment. Like all agricultural commodities, the price of palm oil fluctuates a lot. There’s the risk of pests, disease or unfavourable weather events. A significant amount of palm oil is used for biofuel so there is some regulatory risk associated with reduction of biofuel subsidies or an outright ban of biofuel. Many people have concerns about the health impact of consuming palm oil. And the industry has had a lot of bad press regarding forest clearing, peat fires and loss of wildlife habitat.

I have some pretty strong views on these areas. For full disclosure I previously worked in the vegetable oil industry (including palm oil milling) and still do a small amount of work for a palm fruit milling machinery company. So you could say that I’m biased but I have at least seen what goes on at well managed mills in Malaysia, Indonesia and PNG. My opinion is that most of the bad publicity is undeserved and that unless people everywhere decide to accept a major downgrade in their diet and standard of living, palm oil is going to be part of our diet for the foreseeable future.

Previously, most of the hard fats in our diet came from animal fats such as tallow, lard and milk fat. Vegetarianism (and also halal and kosher requirements) made the first of those two unacceptable for many consumer products and veganism reduced the addressable market for the third. For a period, hydrogenated seed oil (mostly soy) provided an acceptable alternative. Unfortunately, health concerns regarding trans fat meant that hydrogenated oils became unpopular. That left palm. For a large food manufacturer or restaurant chain seeking an oil which makes baked goods fatty (but not oily) or fried food crispy, the oil which will offend the least number of customers from a dietary and religious point of view is palm.

Palm oil (and palm kernel oil) are also very versatile (compared to the main industrial oils) in terms of producing specialty products. The oil can be fractionated simply by chilling it until part of the fat solidifies and filtering the solids out from the liquid. The wide range of fatty acids in the oil make it useful for oleochemicals such as soaps and emulsifiers. It’s currently a very cheap oil – that might not continue in the future. But it will probably always be the easiest oil to manufacture many specialty products from.

In terms of the environmental impact, palm has much less impact than other oils when managed correctly. Palm oil uses a fraction of the area of land per tonne compared to soy, canola and sunflower oils. It also uses a fraction of the fertiliser, pesticide and herbicide per tonne compared to seed oils. Biomass from the pressed palm fruit is used to provide nearly all of the electricity and heat for processing. The main waste product is wastewater which is treated to a high standard (often by recovering biogas for combustion) before release. Based on the numbers alone, palm oil is the oil with the lowest environmental impact by a substantial margin.

Obviously the quantitative inputs aren’t the full story. A small proportion of the industry engages in unethical practices such as illegal clearing, burning etc. There is evidence that shows this is a very small part of the industry and that many of the more visible incidents (such as smoke emissions) that are blamed on the palm oil industry are actually caused by other sources. What I do know is that I haven’t seen anything like that in the (relatively old) plantations I have visited. UP has committed to exceed industry (RSPO) standards and has indicated that any future plantation purchases will only be for pre-2005 brownfield projects. UP’s management isn’t incented to grow the company at any cost. The company has set aside 11% of their land as forest reserve. If you add up the qualitative and quantitative environmental impacts of palm oil it is way ahead of the seed oils – which ironically have received very little bad publicity. The palm oil industry really could do with a well executed public relations campaign or two.

Compared to other crops, palm is pretty good in terms of agricultural risk. It’s not like soy or canola where you could lose an entire crop if the weather is poor. Permanent tree damage is rare. There are weather events such as El Nino which cause water shortages but usually when this happens production declines throughout the industry and the price of oil rises to compensate. There is still a risk that a new type of pest or disease could decimate the industry. I have no way of putting a probability on that except to say that it would be a similar risk to that faced by timber plantations all over the world.

That leaves the commodity price risk concern. All vegetable oil producers are subject to fluctuations in selling prices. The market for commodity oils such as crude or refined palm oil is very competitive and spot prices have fluctuated by +/- 40% over the last 30 years. However, UP’s KLSE listed peers have mostly been continuously profitable during this period. UP’s profitability has been especially stable. ROE has been between 11% and 17% whilst the best of its peers has rarely exceeded single digits. There is something unusual going on here – the bulk of the rest of this write-up is about the reasons for UP’s unusual profitability.

There are three main reasons why I think UP is unusually profitable – infrastructure, management and a special customer relationship.

Infrastructure Edge

UP’s infrastructure can be broken down into plantations/milling and refineries/downstream. One complex of 11 plantations with four mills and one refinery/packing plant is located in Perak, Malaysia. There is also a plantation and mill in Kalimantan, Indonesia and a bulk terminal near Penang in northern Malaysia. It probably sounds odd but I would say that UP’s infrastructure advantage is due to a lack of built-in mistakes rather than a special advantage. UP doesn’t have any infrastructure that couldn’t be replicated by other companies. What it does have is restraint and a lack of short-termism which has allowed the company to correct previous mistakes. UP could become a much larger company by buying plantations and other infrastructure at a rapid rate. But by being very selective about the quality of plantations that they have bought and the way they are developed, UP has stayed relatively small and avoided mistakes which would have significantly eroded shareholder value.

There are a lot of ways a palm oil company can bake long-lasting mistakes into their infrastructure. You really only get one chance to build a mill or set out a plantation – once it is built the cost of rectifying individual mistakes often exceeds the benefit. What often happens is that rectification projects that have less than a three year payback time or are difficult to quantify usually don’t get approved. That means management teams tend to reject projects with an IRR which is less than an arbitrary hurdle rate but significantly greater than their whole-company ROA. In contrast, UP will replant newly purchased plantations even if the existing palms aren’t that old – just because the standard of planting won’t provide the yields they require. By paying attention to a lot of small, boring capital reinvestment details a palm oil company like UP can accumulate a spectacular asset-driven advantage over a long period of time.

The most obvious example of an infrastructure mistake is in the purchase of plantation land and planting of palms. You can certainly grow oil palms on cheaper land which is susceptible to flooding or on the side of a steep hill. But oil palms are difficult to harvest – the fruit bunches are like a 30 kg pine cone stuffed with large olives. These need to be cut down without the bunch landing on the harvester’s head and somehow transported to the mill. You somehow need to get a tractor between the trees in order to broadcast fertiliser. So during good weather your cheap plantation may yield similarly to good quality land but wet weather will prevent access for harvesting and fertilising and so yields will decrease. If the plantation wasn’t properly managed during infancy then the palms may have permanent problems that will persist for another 20 years until they are replanted.

UP have avoided purchasing anything but relatively flat, good quality land and they manage their plantations so meticulously that employees of their competitors will tell you about it. Another example – in Malaysia at least one of UP’s mills loads the fruit into rail cars close to where it is harvested. These rail cars then transport the fruit to the mill and are used to hold the fruit inside the sterilisers which are the first step in the milling process. This sounds a bit boring and obvious but it cuts out a lot of labour cost and fruit damage related yield losses. Strangely, I haven’t heard of another company which does this – probably because hilly topography makes it too expensive.

UP also has its own tissue culture and seed production facilities. This not only means that they likely pay less for their seedlings, it also gives them control of the quality of the seedlings they plant. Given that it takes more than three years before the first harvest, it’s a big problem if mistakes are made in seedling selection.

One other capital expenditure issue specific to the industry is replanting. Oil palms must be replanted every 20 to 25 years or so, otherwise yields decline. If a company falls behind in its replanting schedule then future yields are compromised. Just being frugal doesn’t work – replant and maintenance capex must be spent at just the right time to maintain profitability.

Also, all of the above is not to say that UP have never made infrastructure mistakes. In the past the company has tried to grow by acquiring or setting up agricultural operations in South America and Australia and by investing in a Norwegian fish oil producer. Some of the existing plantations originally had flooding problems. But these mistakes have been divested, shut down or improved and the focus in recent decades seems to be on sticking to activities that UP has been successful at for a long time.

Survival of the Fittest, Not the Fattest

In terms of scale economies, I’m not worried about a competitor gaining an advantage over UP. Palm oil mills tend to max out in capacity at around 120 t/h – larger than this and the distance to the furthest plantation it services combined with the need to process fruit on the day it is harvested makes it more economical to build another mill elsewhere. UP’s Malaysian mills are between 40 and 60 t/h capacity. There are no companies with scale advantages at plantation/mill level. By comparison, soy and canola oil crush plants grow ever larger as the incoming material logistics and shelf life permit silo storage and long-distance transport by rail – fixed costs tend to drive smaller soy and canola mills out of the market.

At refinery level there are scale advantages in the production of commodity products but these are largely negated by changeover and batch size considerations for companies that produce higher-margin specialty products. UP’s two refineries are relatively small and produce mainly specialty products. They are highly integrated – by that I mean that they interact with the company’s mills to make their most of their inputs. For example, biogas from the palm mill effluent is used to fire the refinery boiler. Pipelines allow oil to be sent to the refinery from the mill without using trucks. When companies talk about synergies to justify making overpriced mergers it is often hard to see if the synergies are real. For palm oil businesses the synergies are obvious – you can see most of them from Google maps. In the oil milling industries in general, assuming the absence of scale issues, the company which is best integrated and makes the fewest infrastructure mistakes is the lowest cost producer. In the palm oil industry, that company is UP.

Cost Competitiveness

The only way I am comfortable investing in a commodity company is if I am confident that it can remain profitable during a period of depressed commodity prices. I doubt I can time commodity price cycles but I do think you can do well in commodity companies if you invest in the lowest cost producers when their share prices are depressed. The lowest annual average market price for crude palm oil (CPO) in the last 30 years was MYR 977 per tonne in 2001. At the time UP’s cost of production for CPO was MYR 537/t and their average CPO selling price was MYR 976/t. That year the company still made money on a net profit basis, albeit a lot less than normal. There were other investments negatively impacting UP’s results that year and it is overly simplistic to just look at the CPO price given UP’s product mix but this gives an idea of how robust the company is. UP also produces more value added products now than it did in 2001 so margins should be even more robust in the event of another downturn.

UP’s yields and extraction rates are consistently well above industry averages. Over the last 15 years UP has averaged 43% more oil per hectare than the Malaysian average. That’s a massive difference. Breaking this down, based on the 2018 figures UP extracted around 10% more oil per tonne of fruit than the Malaysian average but extracted 67% more oil per hectare. It’s not possible to attribute the entire 10% of extraction to mill efficiency as the condition of the incoming fruit significantly influences the extraction rate. The bulk of the extra yield clearly comes from the plantations.

UP’s 2018 cost of production was MYR 1,188 per tonne (Malaysia) and MYR 1,253 per tonne (Indonesia). The closest competitor in cost terms that I can find is Sime Darby Plantation Bhd (KLSE:SIMEPLT) at MYR 1,260 per tonne. The other listed majors such as IOI and KLK report figures upwards of MYR 1,370 per tonne. The difference in oil yield per hectare more than accounts for the difference in unit costs – possibly UP spend more on fertiliser and labour than the average plantation but they are more than recouping the extra cost in terms of yield increase.

Management

The reason UP has accumulated quality infrastructure and operated it well over a long period of time is that it has a long history of owner/operator management. The company was founded by a group of Danish shareholders in 1906 and has been owned and operated by people associated with the original shareholders since – with the exception of the Japanese occupation during WW2. Currently, two of the executive directors (Carl and Martin Bek-Nielsen, sons of the previous MD) control 47.8% of the company’s shares.

I haven’t met management but people that I trust have. They have a reputation in the industry for being hands-on, competent and fanatical. There is evidence that they go out of their way to look after their workforce – an important factor given that plantation work is labour intensive and high yields depend on attention to detail by the field workers. Importantly, they have managed to integrate Malaysian shareholders and directors into the business alongside the original Danish interests. Malaysia’s government has mandated varying percentages of Malay ownership of public companies over time – UP is the only one which has successfully retained many long-term European shareholders.

The only thing that I would like to see improved would be a clear succession plan. The current owner/managers clearly play a large role in the business but the company was successful before they or even their father took control. It looks like the company has a strong culture and operational management depth but it would be nice to know who will be allocating UP’s capital in future even though the Bek-Nielsen’s are relatively young.

Ownership Structure and AAK

I believe UP’s ownership structure is also at least partly responsible for their profitability. In the 1970s UP’s management realised that the volatility of refined oil prices threatened long term profitability. They courted a partnership with Danish specialty fat company Aarhus Olie A/S. When the courting didn’t progress very well they bought up a large stake in Aarhus Olie and took a seat on the board. Over time the ownership structure of Aarhus Olie and UP has passed through a few different phases and now United International Enterprises Ltd (CPH:UIE) (which is controlled by the Bek-Nielsens) owns a large stake in both. Aarhus Olie is now known as AarhusKarlshamn (STO:AAK).

Until 2012 (when UP’s executive directors ceased to be directors of AAK), UP sold around ⅓ of its annual revenue to AAK in the form of cocoa butter substitute. UP is no longer required to disclose sales to AAK but I can’t see why the amount sold would have declined. I think this relationship contributes to the margin stability, if not profitability of UP.

Note that I’m not saying UP’s directors have any say in AAK’s procurement process. Even without the ownership overlap, reliability and quality of supply would be important to a company like AAK. I can think of more than one relationship in the commodity food industry where the purchaser acts to keep a supplier profitable due to the disruption caused if the supplier were to compromise on quality or become unreliable in supplying on time. That doesn’t mean they pay them above market rates – it just means they don’t excessively reduce prices when the market is depressed. Also, AAK sells highly differentiated products such as cocoa butter substitute where the performance of the product would be compromised if the raw materials vary even slightly from specification. Industrial buyers of palm oil products need to trust that their suppliers won’t damage their brands through environmental misbehaviour – that adds another layer of trust. There’s a high probability that the UP/AAK relationship would be sticky even if they had different owners.

Safety

Like many listed palm oil companies, UP has no term debt. Financially the company is not risky.

The most obvious threat to the palm oil industry is the availability of labour – the industry has been publicly worrying about the cost of labour for at least 10 years. Malaysian plantations have relied on immigrant labour since colonial times. The number of Malaysians willing to do plantation work has declined as other types of work have become available so the industry has been increasingly reliant on migrant workers in recent years. By my numbers, if UP started paying plantation workers the same rates that US agricultural workers are paid then UP’s production cost for 2018 would increase from MYR 1,188 per tonne of CPO to around MYR 2,698 per tonne. That would make crude palm oil slightly more expensive than crude soy oil. If that happens, palm oil will no longer be a cheap multipurpose oil but it will still be very viable as a specialty oil. I think this is the worst-case scenario in terms of labour risk. Given the high proportion of value-adding that UP does, even an extreme scenario such as this should not present a risk to UP’s survival.

If the worst-case scenario happened then the specialty producers that remained should earn the typical average return on assets for a capital intensive industry – say 8% ROA. However, if one of these integrated businesses also shared ownership with one or more downstream businesses (such as AAK) then they should have more stable sales tonnages than their competitors. That alone won’t mean they will be more profitable – the affiliate customer is not going to pay above the market rate for their raw materials. However if the integrated company also had infrastructure that allowed it to produce at a cost significantly less than the rest of the industry then I would expect that company to earn more than 8% ROA in proportion to their cost advantage, as UP has tended to do.

The palm oil industry contributed around 4% to Malaysia’s GDP in 2018. It also employs a lot of people in rural areas where there is no other work that is as economically productive. There’s a strong incentive for the Malaysian government to continue to permit immigration of plantation workers. The industry is also trying to mechanise but this is easier said than done. Fruit bunch handling can probably be somewhat automated but harvesting and pruning looks to me like tasks that will always require human intervention. It’s hard to picture a situation where the whole industry shuts down due to labour costs – despite nearly 30 years of globalisation there are still plenty of countries nearby Malaysia which are able to supply cheap labour. UP’s competitors have been trying to operate plantation businesses in Africa and South America for years – those operations have not proven to be lower in operating cost than Asian plantations. My expected case scenario is that palm oil production costs remain low compared to other oils for at least the next 15 years and the industry continues to expand until available land constraints are reached.

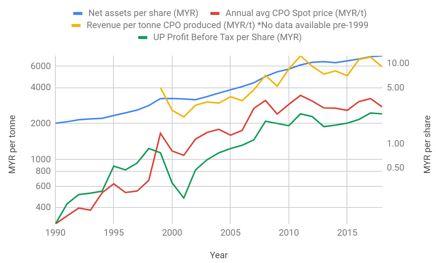

Growth

Since 1999 UP has grown revenue at CAGR 6.1 % and profit before tax at CAGR 7.8%. I’ve chosen 1999 as a starting point mainly because the CPO price was not excessively high nor low at that point. Breaking the revenue increase down, the CPO price increased by CAGR 3.7% and UP’s plantation area increased by CAGR 2.4% over the same period.

The reason for the profit increase is less obvious but I think it comes from increased utilisation of UP’s Unitata refinery. UP doesn’t split out refinery tonnages but if we look at the fraction of plantation revenue going to internal sales, this has increased from 11% in 1999 to more than 80% currently (presumably the remaining 20% is Indonesian CPO production). Refinery operating margins have grown from break-even to around 8% over the same period. That makes sense when compared with the economics of this type of factory. Given that UP uses biogas to fire their refinery boiler, their largest operating expenditure would be operating labour – this would be a very high fixed-cost business.

Does past history provide any guide to UP’s future growth? Possibly. I think UP’s revenues will certainly grow at a pace which at least matches Malaysian inflation due to growth in the CPO price driven by increases in labour costs. The other growth driver I can see is UP’s new refinery. This JV (50% with Fuji Oil) refinery, known as Unifuji, was commissioned in late 2018. At 300 t/d of refining capacity, Unifuji is smaller than Unitata and will produce specialty fat products using solely UP-grown CPO. If margins are similar to Unitata, UP’s share of Unifuji could add a further MYR 102 MM or roughly 20% to UP’s operating profit once the refinery is at capacity. Based on the MYR 145 MM construction cost that may be an excellent return, dependant on how long it takes to reach capacity. This project alone should underwrite growth for UP for the next several years.

Another way to look at growth is that UP has compounded net assets per share at CAGR 7%. Asset growth is comprised mostly of the increased cost of wages and fertiliser used to re-plant the plantations. I would expect this to continue to increase at a similar rate across the industry – all plantation workers in Malaysia are paid at least the government-mandated minimum wage. Malaysian minimum wage has increased at around 5% per annum since 2014 and Indonesian wages have increased to similar levels. In the long run, I expect the CPO price growth rate to be similar to the wage growth rate, otherwise the high-cost producers will need to exit the industry. Given the variability in commodity prices, I think UP’s net asset growth rate is more useful for forecasting long-term growth than revenue growth rates.

Capital Allocation

In terms of capital allocation, I’m very confident that any growth will be value additive, not just growth for growth’s sake. Due to UP’s strict requirements any purchases of plantation land will be entirely dependant on parcels of suitable land coming up for sale – despite this happening rarely, management hasn’t been tempted into buying substandard land. Current management also aborted an oleochemicals JV in 2015 when it was realised that there wasn’t sufficient demand. I’m going to repeat myself but this is important to the whole thesis – replanting is very well disciplined with no tendency to hold back replanting to boost short term results.

Past acquisitions have usually been paid for using cash. The company’s share count hasn’t increased since 2002 when scrip was issued to pay for the acquisition of plantations from an affiliate company. In that transaction the company increased the number of issued shares by 37% in order to increase the plantation area of the company by 48% so that seems like a reasonable transaction even though UP’s shares were undervalued at the time.

UP pays an annual dividend commensurate with profitability and capex requirements. Like most Malaysian listed companies, UP has had shareholder approval for a share buyback in place for some time but not exercised it.

Valuation

Historically, UP has compounded tangible book per share at around 7% and paid an average of 8.7% of tangible book in dividends each year. If you expect the market index to deliver 8% returns for the foreseeable future, and expect UP to keep growing at the same rate then UP should be priced at around 2x tangible book. This has been the case since around 2012 – UP is not an underfollowed stock. By comparison, most other palm oil companies should sell for a multiple of book value which relates to their ROE but they tend to be split between smaller, pure-play plantation stocks which sell for a fraction of book or larger conglomerates with other interests (e.g. property development) which sell for up to 3x tangible book.

I want to buy UP because I believe it will reliably (if lumpily) produce above average returns, is very safe, and has potential for profitable growth. The reason I spent the time to research UP is because fluctuations in the CPO price (e.g. if the EU bans palm oil use in biofuel) might give me a chance to buy, even if low central bank interest rates make it too expensive to buy other quality stocks. In the early 2000s, the CPO price was depressed and UP traded for around 1x tangible book. If that happens again then UP would produce a running return of around 8%, even if it stopped growing, with the potential for single-digit revenue growth and a doubling of the share price once the CPO market rebounds. Tangible book per share is around MYR 12.50 at the moment.

I haven’t yet researched UIE and AAK in detail but these provide another way to access the capital management skills of the major shareholders/managers. Apart from UP and AAK, UIE holds shares in a number of other companies and seems to be a vehicle for reinvesting dividends from UP – I may write up UIE in future. For further reading on UP I highly recommend The UP Saga by Susan Martin – it’s quite an enjoyable read and covers the company’s history from 1906 until the 1990s.

Disclosure: The author doesn’t own any of the securities mentioned at the time of writing. This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any securities, nor is it financial advice. All information presented is believed to be reliable and is for information purposes only. Do heaps of your own research before purchasing any security.