Burford Capital Limited LSE (AIM): BUR

Recommendation: Buy

Burford Capital is complicated to value; and so vulnerable to opportunistic short sellers, but this weakness offers opportunities to long term investors.

Stephen Gamble, writer and analyst, 12th October 2019.

Stephen Gamble, writer and analyst, 12th October 2019.

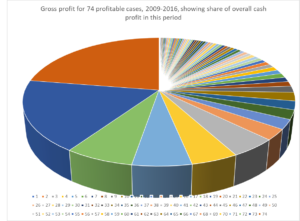

Figure Above: shows how each of 74 concluded matters in period 2009-2016 contributed to profits in this period – 4 matters make up 50% of gross profits, 11 matters make up 75% of gross profits

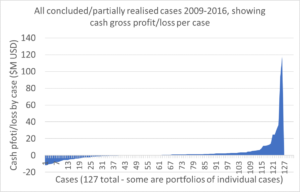

Figure Above: shows gross cash profit/loss for each of the 127 matters concluded/partially realised in period 2009-2016. 58% of cases give a positive return, the rest break even or lose money.

Overview

Burford Capital is in litigation finance, a relatively new industry in a growth phase, with complex assets. The recent attack from short sellers give rise to opportunity for longer term investors.

Lawsuits are risky for companies: they have to commit large amounts of capital up front to pay for expensive lawyers, they can take years to settle, and the return on their investment is unknown until the end, and binary: either a large cash windfall, or else a total loss, and they may even face a liability for costs of the other party. Furthermore, once litigation has started, it has to be seen through to the end in order to prevent a total loss of money invested. This often takes multiple appeals, making the total cost difficult/impossible to ascertain at the start. In summary, lawsuits can be difficult to justify to shareholders since the duration, cost and outcome are inherently uncertain. However, they are often desirable in order to protect key business interests – so the companies are left with a difficult choice when considering whether to litigate or not.

It is at this point that companies considering a lawsuit, are increasingly turning to a third party litigation finance company. They can provide capital, to avoid the problems discussed above, and in return, they take a slice of the outcome. Therefore they do not need to spend money at any point in the litigation process, e.g. on lawyers etc. since the litigation finance company will spend its money instead. This changes litigation from an uncertain and risky enterprise into a simple opportunity cost – that they might have made more money, if they had paid the lawyers themselves. It also incentivises companies to pursue litigation that they might otherwise have deemed too risky. For the company, the cost of making ~30% less money in victory or settlement, is much preferable to the risk of committing an unknown amount of money for an unknown duration, where if the commitment is not followed through to the end, all the money invested is lost. Furthermore, in many cases the company still retains some control over the litigation, and can input into the strategy pursued – without having any financial risk. Litigation finance can be crudely characterised as a ‘corporate no win, no fee,’ claims industry.

This industry is a relatively immature one compared to the personal claims one, which is widely advertised and well known, and so it is helpful to consider its history. The first listed litigation finance company was IMF Bentham (where IMF = insolvency management fund), who were founded to invest in insolvencies, but changed the direction of their business in 2001 by purchasing a litigation finance business, and re-listed on the Australian stock market in October 2001, raising $10M AUD despite the inauspicious timing. Until 1993 in Australia, it was illegal to practise either champerty (litigation finance) or maintenance (encouraging and supporting a party to take up a lawsuit), at which point both were legalised. Laws preventing champerty and maintenance were originally devised in medieval England, to prevent unscrupulous people with money and political power, bringing fraudulent or doubtful claims against other parties. In some jurisdictions, e.g. Ireland, champerty and maintenance are still illegal, so litigation finance is not possible. Singapore passed a bill in 2017 allowing litigation funding for the first time, by abolishing torts for maintenance and champerty. There is a global trend towards acceptance of third-party litigation funding.

The next company to float was Burford Capital in 2009 on the AIM market in the UK, raising £180M GBP ($234M USD) in an IPO and secondary placing in 2009-2010. Although it is listed in the UK, it reports in USD and the majority of its cases are denominated in USD. It was co-founded by Jonathan Molot, a Georgetown Law Professor who is the Chief Investment Officer, and Chris Bogart, CEO, who was formerly the general counsel at Time Warner and CEO of their broadband business. Both owned a stake of about 4% in Burford (having sold half of their original 8% stake each), until after the short attack when they bought a further £3M between them taking their combined stake back up to 8.3%. It appears that Burford has very good executive relations, since the senior team has been in post since the company formation, e.g. the co-founders, Jonathan Molot (chief investment officer) and Chris Bogart (CEO). Jonathan Molot recently expressed that he was committed to Burford for the longer term.

Burford is profitable, and enjoys considerable tax advantages since it is incorporated in Guernsey as an investment fund, therefore being exempt from corporation tax. Some subsidiaries pay corporation tax, but due to movement in the value of its investments in 2018, and a tax-write off related to an amortisation of the acquisition of the law firm Gerchen Keller, Burford recorded a $12M tax credit as a deferred tax asset. Note that two of Burford’s competitors: Manolete Partners (listed on LSE in December 2018) and Litigation Capital Management (LCM) who listed on the Australian stock market in December 2016, then transferred to AIM in December 2018, have effective tax rates of 21% and 28% respectively.

There are also multiple private companies, e.g. Therium, Harbour Ligation Finance, Woodsford Ligation Funding Ltd, etc. All companies are growing, and the size of the addressable litigation finance market is not known, but is estimated at $200B – $900B by Burford Capital. Burford also commissioned a survey of lawyers which shows the awareness and take-up of litigation funding is increasing significantly in the last few years in multiple countries around the world.

Burford has recently been the subject of a lot of negative publicity – a short seller firm in the US called ‘Muddy Waters Capital,’ issued a highly critical report on Burford, criticising mainly their accounting practices relating to how they report earnings, specifically cash earnings vs ‘fair value,’ increases in their investments, and corporate governance. Their reports, and Burford’s responses are, discussed further in the durability and quality sections below. Due to this controversy, Burford has indicated that it will seek a US equity secondary listing. The consequence was a significant share price fall from around 1500 pence to around 800 pence, and the share price has not recovered since beyond approximately this level.

The board consists of four people, who have each served for more than ten years. Unusually the CEO does not sit on the board. Due to shareholder criticism following the Muddy Waters report, Chris Bogart will join the board, the chairman Sir Peter Middleton will resign after two more independent directors are added, and also the CFO Elizabeth O’Connell (Chris Bogart’s wife) has been replaced by Jim Kilman, a former Vice Chairman of investment banking at Morgan Stanley, who was Burford’s investment banker when he worked at Morgan Stanley, so he is familiar with the business. One of Burford’s non-executive directors, Charles Parkinson is a former Treasury Minister of Guernsey, and current chair of the Guernsey trade association. Another non-exec David Lowe is a former judge who sat in Guernsey. Therefore the company is closely connected to the Guernsey political establishment.

There are various types of litigation finance, and Burford Capital is an innovator in this area. Initially Burford focussed solely on litigation finance, funding individual cases, but has expanded in the last couple of years to portfolio finance, where it takes on multiple cases for one law firm, and also ‘complex strategies/principal investing,’ where Burford takes an equity position in the company so it can pursue the litigation claim directly – often hedging the equity. The latter allows Burford to control the litigation process, e.g. it can choose to settle early – which allows more control over the timing of cash flows. While settlement reduces the overall return on successful cases vs return from a final judgement, it improves the annualised return, by freeing up capital sooner, and also reduces the number of cases lost. Burford has also started asset recoveries, where it pursues litigation to obtain money from company by enforcing judgements/settlements – recently transitioning from selling their lawyers’ services, to a contingent risk model where Burford gets a slice of the assets recovered instead, which is more profitable. The third type of new business is post-settlement investments, where Burford essentially acts as a factoring service. For example, if a client is owed a large settlement, but the process of getting paid is taking too long, Burford will pay the money in exchange for a slice of the settlement. The fourth type of new business is legal risk management, for example Burford takes on responsibilities for adverse costs in return for a fee – i.e. a type of specialist insurance. In 2018, Burford has formed a new wholly-owned insurer to do this: Burford Worldwide Insurance Limited. Burford has in house experience of providing legal insurance, since had previously purchased a ‘after-the-event,’ legal insurer called FirstAssist in 2012 to enter the UK market, but ran down its book of business. All of these businesses have the same characteristics where Burford supplies capital, and/or takes on risk in the short term in exchange for a bigger part of the return in the longer term. Taken together, in 2018 these four strategies made up 23% of its total investment portfolio, but 50% of 2018’s new investments, so these are a growing area and their success is critical for future growth and profits.

Burford invests both capital on its balance sheet, and also capital from funds it manages for other investors, getting both a cut in the profits, ‘performance fees,’ and also management fees. This is discussed in more detail later in the report.

Burford’s chief investment officer Jonathan Molot is a law professor at Georgetown in Washington D.C., and is an internationally renowned litigation finance expert, and write articles and papers about this, including two lengthy papers in 2009 and 2010 about the market for litigation finance. Burford’s research and development efforts to develop new legal finance models and routes to market are probably led and significantly benefit from having a world-renowned expert in the field, who is undoubtedly well-connected to other legal academics, so Burford punches above its weight in R&D strength despite having only 120 employees (including 50 lawyers). This can also be seen in how Burford has innovated new models of litigation finance, such as portfolio finance.

Durability

Burford has been consistently profitable for the ten years of its existence, is the single biggest player in an expanding market, and is growing rapidly. It has recently been attacked by a short seller over accounting and governance, causing a significant and sustained share price fall of ~50%.

Burford is seemingly not subject to individual customer risks: in 2018 half of its investments were in the USA, a quarter in Europe, a fifth were global, i.e. in more than one continent. No one client has more than 5% of Burford’s assets invested. In 2018 Burford was invested in 108 separate cases, with 1118 underlying claims. However, one of the claims in the Muddy Waters short report, was that most of Buford’s profits came from relatively few cases – it then excluded those profits when making calculations about Burford. Burford issued in 2018 a document describing all of its investments to date. An analysis of concluded and partially realised investments, shows that it is correct that the majority of Burford’s profits come from a few cases in this period – see the figure at the start of this report. This implies that it will experience earnings volatility – though the large number of overall cases should reduce this volatility. Management refuse to provide forward earnings guidance, as a result of the natural volatility of earnings.

The company is capitalised at 1.8x total debt: EBITDA in 2018, which is stable over the last four years – i.e. the company has issued debt over the last four years as the balance sheet of investment has grown, in order to keep this ratio constant. Its bond maturities are due starting 2022, laddered so they mature once per year, and each issue taken separately, is covered several times by cash flow. For example, this first issue is £90M or $113M, and 2018 cash recoveries from investments were ~$600M. Therefore Burford will be able to easily repay them as they come due, from profits, or if necessary by shrinking the balance sheet. Investment turnover is fairly rapid – time from investment to deployment is a weighted average of 1.7 years currently. Therefore, even if Burford is not able to raise new capital due to the sharp fall in share price after the short report by Muddy Waters, it will easily be able to meet its obligations to repay bonds. The bonds expiring soonest in 2022 fell from 108p pre short report, to about 90 p at their low, but have since recovered to 96p as of the start of Oct-19, so they are now yielding 6.8% vs a coupon of 6.5%. Their ability to repay bonds contrasts to their competitor IMF Bentham, which had bonds mature in 2018 and chose to sell off part of its investment portfolio into a fund. They acknowledge that they sold at less than its fair value. They have also another bond issue which just matured in June 2019.

Burford has not made a loss in the ten years of its existence. Its profit margins have varied, but have tended to improve over time. One of the ways it maintains profit margins, is by allocating its own capital to the higher profit investments, and the external capital it manages for others, to the lower profit opportunities. For example, traditional litigation finance opportunities are allocated 42% to Burford’s balance sheet, and 58% to funds Burford manages, whereas complex strategies investments are 100% on their balance sheet. They are also seeking to improve profit margins – an example of this is their recent $1B agreement with a sovereign wealth fund. Under this agreement, Burford commits to investing 33% of the capital, but gets 60% of the performance of the fund after capital is repaid. They also get a management fee pro rata to deployed capital, up to $11M/year, before profits are shared. Furthermore, investments are considered individually, so if an investment concludes, Burford is paid. This is often not the case for other fund arrangements – many funds in litigation finance industry, including some of Burford’s funds, have a ‘European,’ structure where all of the investors capital has to be repaid before any performance fees are taken. The $1B sovereign wealth fund performance fee structure, essentially allows Burford to increase the return on its capital by 60%/33% = 1.8x, i.e. it is similar to the benefit obtained by using leverage, but with less cost and risk. The arrangement was made in 2018, and if it delivers a good return for the sovereign wealth fund, may lead to future replication.

In 2018 Burford did a 3 hour webcast all about their business, and emphasized their staff biographies, and also multiple people from the business presented on their areas of responsibility. By reviewing the biographies of the staff, there are a number of senior managers with impressive track records, working for large corporations, and it is interesting that they have chosen to come work for a relatively small company (<$2.5B market cap). This indicates that they see a lot of potential in Burford. Furthermore, staff turnover is very low – of their 90 staff only four have left since the company was founded, and of these, one retired and one died, so staff morale appears to be high.

Burford’s management appear to have integrity – they have created accounting controls within the business which ensure that cash cannot be transferred within the business without the involvement of two teams, and at least three people. Senior executives do not have access to the payments system at all. Their senior management, i.e. CEO, CFO, chief investment officer, are not associated with any previous frauds or scandals, and have worked in various large corporations over the past twenty years. Furthermore, the description of the level of auditing that is carried out on Burford suggests a transparent approach, and the annual report explains the accounting policies in detail. Notes of caution in the annual report are sounded – if the management think that an uptick in a certain metric, e.g. investment returns is temporary then they say so. It is also interesting to note that Burford refuses to provide earnings guidance. They warn that earnings may be lumpy or irregular due to the nature of their business, and so refuse to speculate about future earnings directly. This is useful since it puts less pressure on their employees to move income in order to make up targets or numbers, to meet short term quarterly earnings targets. They have also explicitly stated that employee bonuses are not linked to the value of the investments made by a formula, so employees are not tempted to make propose risky investments to increase their bonuses.

This approach may be compared with one of their competitors, IMF Bentham, who in their 2018 annual report prominently present a metric called the ‘Enterprise Portfolio Value,’ which is cited as having increased 41% annually over the last three years from $2B AUD to $5B AUD. They have a graph to show this – but in the small print of the footnote, it says that the metric is IMF Bentham’s estimate of the total recoverable amount in the claims it is part of, taking into account the defendant’s ability to meet the claim. However, this is not the same as the amount being claimed by funded claimants in the investment, and it is not the estimated return to IMF Bentham if the claim is successful. Furthermore, it is a non-IFRS measure and is also not reviewed or audited. Therefore it is not a meaningful metric in terms of understanding IMF Bentham’s financial performance. Burford does not quote any equivalent metric in its annual reports – instead valuing it’s share of the litigation matters it is entitled to, at fair value. It issued a detailed table of all of its investments, and in this table, figures quoted relate solely to Burford’s share of the total investment. It is important to note that determining ‘fair value,’ requires subjective judgement. The process for doing so is described in Burford’s annual report, and is reviewed and audited by the company’s auditors, and is discussed further in the quality section. This method was disputed by Muddy Waters in their short report, and so this is a key part of the business to understand. In summary: Burford is transparent in that it reports earnings including fair value increases, and also cash recoveries. However, the method used to determine ‘fair value,’ is partially opaque – see the quality section for more discussion of this.

The Muddy Water’s short reports are a test for Burford Capital – their first major crisis as a public company. Burford published a table in 2018 detailing the cost of their investments by type, year, and the realised cash and fair value increases. This is also all audited by their independent auditors. The Muddy Waters short report led to a halving of their share price at the start of August-19, which has not recovered significantly at the time of writing (Oct-19). The complex nature of Burford’s business, and the nature of its assets which are hard to value, may make it difficult for investors to determine the validity of their claims vs the Muddy Waters report. This may affect the longer term durability of the company – Burford will thrive better if it can fully address the concerns of shareholders, and make its business more transparent to investors. Some shareholders have commented that the incorporation in Guernsey, and also listing on AIM on the LSE, could be a way of avoiding scrutiny, due to the lower regulatory requirements in this jurisdiction and stock exchange. To address these criticisms, management have stated their intention to seek a dual listing in the US and UK. While Burford is complex and its ‘fair value’ assessments are difficult to understand for investors, their assumptions are all clearly laid out in the annual report, and the company can be valued on cash returns only if desired, instead of cash returns plus fair value increases. Given the volatility and current level of Burford’s share price, a current value of $10/share is assumed, unless otherwise stated. Shares listed on AIM are quoted in GBP pence, where GBP £1 = 100 pence. $10/share is equivalent to 800 pence, at the current exchange rate of $1 USD = 80 pence or 0.8 GBP.

Quality

Assessing quality of earnings is fundamental to understanding and valuing Burford – this is the most important section of this report.

Reported EBIDTA is calculated as: (1) net realised gain for the year + (2) increase in fair value of investments (net of transfers to realisations) – (3) total operating expenses (staff costs and overheads). Net realised gain is the amount that concluded litigation investments have returned in cash, above the fair value that they were held at on the books. It is essential to understand how fair value is determined. Burford splits its investment assets into three categories when determining fair value, levels 1, 2 and 3. Level 1 comprises easily priced investments, e.g. where there is a current market price, level 2 where a price can be either directly determined or derived from other market prices (e.g. infrequently quoted equities), and finally level 3, which there is no observable market data to price the assets. Level 3 investments make up 84% of Burford’s assets in 2018. A typical example is Burford’s share in the financial proceeds of a court trial. Initially investments in a trial are held at cost, and subsequently, fair value for these investments is determined every six months, using inputs such as contracts, trial progress/risks information, timing of expected cash flows, and other relevant documents. These reviews are given to the Audit committee and the independent auditors (Ernst & Young), who have been the auditors since the company went public in 2009. Burford states that changes to the fair value are only made when there is a concrete development in the case, e.g. an offer of settlement, or an interim judgement. At FY2018, Burford reported that 39% of the total valuation of its investments was comprised of fair value increases, the balance being the cost in the investment in cash – P30 on the annual report.

The fair value methodology was criticised by Muddy Waters in their short reports. In response, at the end of September Burford issued a rebuttal report on their website, which examined the impact of fair value adjustments across all of their concluded investments to date, of the core litigation finance investment type (i.e. excluding complex strategies and asset recovery type investments). This represents 76 of the 127 investments concluded to date, or 60% of their concluded investments. Key points from this are:

- 34% of the concluded investments had a fair value change during their lifetimes

- Of the investments with fair value increases, these increases represented 33% of the final realised profit ($124M fair value increases vs $374M realised profits)

- Of the investments with fair value decreases, these decreases represented 47% of the final realised losses

Therefore, when Burford does fair value increases, it is not overvaluing its investments – in only one case did it write up fair value by more than $1M and the investment subsequently resulted in a loss. Therefore, if the method applied for fair value adjustments is consistent over time, this should continue to be the case. The same people who valued these investments, are still in charge and valuing all current investments, and the same auditors who oversaw the process are still in place, so it is likely that the valuation methodology has not changed. Burford also state that they are required to use fair value accounting under IFRS, and also that they do not capitalise all of the expenses in running a case, and their staff costs etc, so all of these are expensed and affect earnings.

To understand a typical earnings breakdown for Burford, 2018 is taken as an example. Net realised gain for the year (1) was $171M, increase in fair value (2) was $230M, total operating expenses (3) was $70M. Therefore realised cash earnings comprise 43% of the reported earnings, which has held between 35% and 43% over the last three years. However, one has to take into account the rapid expansion of the Burford balance sheet over the last three years. NTA/share has grown from $2.70 in 2016, to $7.37 in 2018, so 65% annualised. Given that the weighted average time from investment to maturity for Burford is between 1.5 years – 2.1 years in 2014-2018 (currently 1.8 years), it is reasonable to expect that the majority of income will manifest as increases in fair value. The next logical question to ask is whether the estimates of fair value gains are excessive. This was discussed above, and also is unlikely because when investments are concluded, there is a positive net realised gain for investments, since 2009. Furthermore, one can look at unrealised gains, which are investments that have been assigned a fair value but have not concluded – some court cases can take years to resolve. This is currently about 39% of total assets – but pre-2014, there is only a total of $4.4M in the years 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2013. This shows that the cases do ultimately resolve, and lead to cash realisations.

Another way of looking at this is to consider what the cash return on assets is: i.e. net cash realised gains/total invested capital in litigation matters two years before this, (to account for the time lag between investment and recovery). If this is done by taking 2018’s net realised gains and the 2016 total capital, figures of 31% for 2018, 36% for 2017, and 18% for 2016 are obtained. This is a strict test since 2 years is about the average duration of investments, which implies that this is only measuring the return on half the investments (i.e. excluding all gains seen in 2017 and 2019). Therefore, the actual final cash profits of the 2016 vintage of investments are likely to be more than this.

However, as an even stricter test, since as a shareholder one is interested in the earnings vs assets invested in the current year, when 2018 cash net realised gains are divided by 2018 total invested capital in litigation matters, then a figure of 10% cash earnings for 2018 is obtained, 11% for 2017, and 8% for 2017. Given that total invested capital in litigation matters increased by 65% annually during this period, and the typical time lag is ~2 years, this is very impressive performance. Put another way, the company is yielding 10% growth in cash on its balance sheet – even on the unrealistic assumption that it scales back its reinvestments to the level of two years ago, and also that none of the investment made in the last two years contributes to growth.

Therefore, if Burford is increasing its balance sheet rapidly, this will not increase earnings in the same year, but will increase earnings two years from now – this is the average investment duration. Therefore if the company is valued solely on a price: earnings ratio, it will be undervalued when experiencing strong growth. Given the time lag between investment and recovery, assuming that investments continue to be made at the same quality over time, then growth over a 2 year period is assured, and the price multiple that the investor pays now, whether price/earnings, EV/EBITDA etc, is higher than the true multiple.

Burford’s profit margins may be compared with its publicly listed competitors, of which only IMF Bentham has been public for a significant period of time – which made a loss in 2018 in all three geographies they operate in, i.e. Canada, US and Australia. IMF Bentham has 73 permanent staff, which cost $15M USD ($0.2M each), managing net assets of $253M USD ($3.5M USD per staff member), vs Burford which has 120 permanent staff, which cost $50M USD, ($0.4M each), managing net assets of $1.2B, or $10M each. Therefore Burford’s staff cost an average of twice as much, but manage three times as much money each as IMF Bentham’s staff – so Burford operates more efficiently than its main listed competitor. Burford’s accounting controls are good – they also have a system whereby the valuations of each individual investment is shared with their auditors.

Burford also does not capitalise its expenses, and add them the investment portfolio balance, but IMF Bentham does. For Burford, this means that their operating expenses line in the income statement accurately reflects the cash expense of operating the business.

Earnings will be subject to some volatility: due to most of the profits coming from a few cases – see figure 1 at the start of this report. the average two year lag return on investments has been 21% over the period 2012-2018, with a high of 36% and a low of 5%. The standard deviation is 11%, and the coefficient of variation is 52%, i.e. one standard deviation represents half of their earnings. Having said this, earnings with a two year lag have been higher in the past four years, with a low of 18% and a high of 36%, where one standard deviation is 6%, and the coefficient of variation is 31%. Burford is increasing its fund management business, which gives recurring management fee income which is more stable, and also focussing more on asset recovery, complex strategies, and other investment types which give them more control over timing and predictability of income.

Moat

Burford has scale, innovation, mindshare, customer retention, and cost advantages.

The litigation finance industry has been around since about 2002, since IMF Bentham started. Burford has several competitive advantages, namely: scale, innovation, mindshare, customer retention, and low cost – these will be discussed in more detail below.

Burford is 4x larger than its next largest competitor, which is Harbour Litigation Funding, which is about 30% bigger than the next largest competitor, IMF Bentham, in terms of public/private debt and equity raised for litigation finance investments. Of the ten competitors listed in Burford’s 2018 capital markets webcast, all were started in 2013 or earlier, and all are private except IMF Bentham. Therefore, none have grown anywhere near as fast as IMF Bentham. Either Burford is taking share in this market, or else it is creating new markets due to innovation.

Burford has pioneered a number of different types of litigation finance, namely complex strategies, asset recovery, and portfolio financing. Complex strategies are where Burford takes a hedged equity stake in a client, so that it can pursue litigation directly, and therefore controls the litigation process. If the outcome is successful, they can see gains in the equity stake, and controlling the process gives them choice as to if/when to settle, so they have some level of control over the timing of cash flows from the investment. Asset recovery is when companies give Burford a stake in the cash recovered from being paid for a successful claim, when they are having trouble getting the defendant to pay up. Portfolio financing is where Burford finances a pool of claims which are cross-collateralised from a client. In this case, there are multiple paths to recoveries so although returns are lower for each matter, the loss rate is lower so overall returns are higher. Together, these three strategies made up 50% of new financing in 2018.

Burford had a market research survey carried out to examine brand awareness of litigation finance companies within the industry, surveying 38 lawyers from ten counties with interviews, and also 495 lawyers though an online survey. It was found that they have significant mindshare amongst lawyers: 63% named Burford as the litigation finance they were most familiar with. Therefore Burford seems to have good mindshare amongst lawyers.

In terms of customer retention, Burford has said that 75% of firms who use it for single case finance, go on to use it again, and also some customers have committed not just one case, but a portfolio of cases to Burford, indicating that they are happy to have an ongoing relationship – they are unlikely to switch away to another provider of finance until those cases are concluded at least.

In terms of cost of operations, Burford pays its staff twice as well on average, than its main publicly listed competitor IMF Bentham, as discussed above in the Quality section. However, balance sheet assets under management are three times higher at Burford, so it is run more efficiently. This also suggests that Burford is likely to enjoy better employee retention and have better employee relations. Burford has only lost four employees out of 90 since it was formed, and of those, one retired and one died. Comparing executive compensation: IMF Bentham runs a LTIP (long term incentive plan (LTIP), which sets a fairly low bar for its senior staff to meet: over a rolling three year period, rights to buy shares will vest if the following conditions are met. 50% of it is awarded if total shareholder return is positive and in the 75% percentile, compared to a basket of other financial Australian listed companies, and 50% if compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of assets under management is >7%. The value of these rights are 65% of the base salary, for example in 2018 1.7M performance rights were issued, equivalent to 0.8% of outstanding share capital. In the case of Burford, the LTIP is equally weighed between: total shareholder return vs a group of public companies, EPS growth after removal of non-cash items, and growth in aggregate asset value, vs gross cash receipts from investments. In 2018, 289,000 share rights were awarded, which is ~$2M or 0.05% of market cap. Furthermore, the Burford plan has measures incorporating actual earnings, or cash received, whereas the IMF Bentham plan has measures that do not directly measure shareholder value creation, just share price and assets under management. The Burford plan has almost insignificant dilution to shareholders, while the IMF Bentham gives about 1% dilution if all rights are vested.

Another aspect of the business peculiar to the industry involved, is that although it is a fairly new industry, all of Burford competitors have been in operation for at least six years, and many ten years or more. Burford has been in operation for ten years, and yet it is much larger and growing much faster than all its competitors, indicating that it is an outstanding business in relation to its competition.

In terms of sales strength, Burford is moving to develop their sales organisation – prior to 2018, they did not have dedicated business development people, relying instead of the networks of their lawyers to bring in business, plus unsolicited enquiries. They have hired business development professionals, in an effort to pre-filter opportunities that come to their lawyers for consideration. This is discussed in the 2018 annual report, and Burford have revealed that they have increased the percentage of opportunities in their pipeline that are ultimately funded, but not increased their pipeline size dramatically, i.e. they claim that their pipeline quality has improved, while maintaining the same investment standards.

Capital allocation

Burford finances its strong growth by reinvesting 92% of earnings, raising debt and occasional equity raises. Acquisitions are limited and strategic in nature.

Burford pays a minimal dividend, in the last two years equivalent to 8% of earnings. This has reduced as a percentage of earnings over time from about 30% five years ago, in order to reinvest earnings instead. When a small amount of capital was required to purchase an asset management business, Gerchen Keller, Burford issued $22.5M new shares to part pay for the acquisition, but it was majority funded with debt and cash. The purchase price is also amortised over time, giving a tax write-off. Burford is pursuing a growth strategy, taking on debt, and issuing shares in order to grow the balance sheet of assets over time, since they can earn good returns on capital invested. At the IPO in 2009, 80M shares were issued at £1 each, now there are 219M at ~£8 each, i.e. the price after the recent share price fall. This means a share price CAGR, after adjusting for dilution, for the original shareholders, of 12% annually, excluding dividends, or 14% including dividends. This is calculated as: total shareholder invested funds of $596M, and current market cap is calculated as: share price 800 por $10, multiplied by 219M shares is $2187M. Dividends from 2009-2019 are $131M total paid out.

Debt: EBITDA has been maintained at around 1.8x as EBITDA has grown year on year. Burford state that they are still trying to define the optimal strategy between raising debt, equity and reinvestment of earnings. Their cost of debt is about 6%-7% on average. Burford won an award for innovation in raising $180M of USD denominated bonds on the London Stock Exchange, the first company to raise bonds denominated in USD in London on the retail investors order book on the LSE.

Burford is a capital intensive business – it needs to reinvest capital in order to maintain its earnings, and also to grow. Therefore, if it is forced to repay the bonds maturing over the next five years, rather than refinancing them, due to the controversy about the company from the Muddy Waters short attack, it may have to shrink its balance sheet, which will lead to lower earnings. However, offsetting this will be increases in the amount of capital coming from retained earnings in the business. The first bonds are due 2022, and are laddered for several years after that.

Value

Burford currently benefits from a significant tax advantage, and so should be valued at a higher EV/EBITDA ratio than competitors.

Burford’s assets consist of two main categories: on balance sheet assets, and private capital managed by it with management and performance fees. For the purposes of this discussion, the on balance sheet assets will be mainly considered. As discussed in the quality section, there is a two year weighed average lag between making investments and receiving a return. Net assets at the end of 2018 were $1.2B, and growing strongly. This total asset value consists of mainly Burford’s interest in the outcome of legal cases it has invested in. Of this, 39% is unrealised ‘fair value’ gains, previously discussed, the balance is the initial cost of the investment. There is a significant degree of discretion in how to value these assets since they have no quoted price, and Burford describes how this is done in its annual report – again this is discussed in the Quality section above. To summarise, net assets may be used to predict future earnings. Earnings are partially cash based, and partially unrealised gains which take longer to convert to cash.

The company as a whole should be valued at a higher multiple than its competitors, since it pays effectively no tax due to being incorporated in Guernsey as an investment fund, vs a tax rate of 21% and 28% for two of its listed competitors, IMF Bentham (12.3x EV/EBIDTDA in 2017, last profitable year), and Litigation Capital Management (14.1x EV/EBITDA). Burford is currently valued at 7.2x EV/EBITDA after the share price fall, but according to the tax rate difference should be valued at 7*1.25 = 9x, or 25% higher than its current valuation, solely on the basis of the tax differences.

Burford is also listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) of the London Stock Exchange, and AIM shares held more than two years are exempt from inheritance tax, when they are passed on in an estate. Bizarrely, AIM shares do not count as listed shares for the purposes of inheritance tax. In the UK, inheritance tax is 40% of assets above a personal threshold of £325k or $0.43M. The UK average house price is £256k or $0.33M. Since a small but significant minority of UK people have to pay inheritance tax, this is an attractive benefit for them.

Growth

Burford is growing net assets at 26% CAGR over five years, and EBITDA at 42% CAGR over five years, with a very long ramp for growth available.

Burford seems to have products with sufficient market potential to sizeably increase its sales over the next five years. Indeed, net assets are a leading indicator of profits for the next couple of years. The litigation finance market is a relatively untapped one; which Burford has suggested can be considered in various ways:

- Annual legal fee revenue $580B-$800B

- Largest 200 US law firms have annual revenues of $100B

- US tort costs annually are $429B

Even if Burford takes a small part of this market, they still have very substantial growth potential based on their current size, e.g. with earnings of about $0.5B in 2018, they could grow at 25% annually for ten years and still have only $6B in earnings.

The management seem quite determined to continue to develop products which will further increase sales potential, e.g. complex strategies investments, asset recoveries, post-settlement claims, and also adverse cost insurance. One interesting thing to watch will be the transition from business acquisition from personal referrals/advertising between lawyers, to Burford sourcing leads from dedicated business development professionals. They have started to develop a dedicated sales force for sourcing leads. There is no sign currently of margin erosion due to competition, since the penetration of litigation finance in the legal market is relatively low, and it is expected that this will continue to be the case for at least the next few years, so the business seems easily scalable to at least ten times the size. This could however, be a future challenge to growth in the 5-10 year time horizon.

One of the other challenges to potential future large growth, will likely be the effective development of a good depth of management talent. Currently, the non-executive board review all major investments, and so do the top executive team. It is unclear at which point this will become impossible due to the increasing number of Burford’s investments, but this would be a good question for an analyst to ask. This is also critical, since this team determine fair value, which is also a key part of Burford’s earnings, so if this team changes, the consistency of this over time could change.

It is difficult to determine if Burford is taking market share vs its competitors, since the total addressable market size is unclear, and they are also inventing new products and creating new markets, but it is true to say that they are growing faster than their listed and private competition. Therefore, it may not matter in a fairly fast-growing market whether they are taking share.

One other interesting feature of listed companies in the litigation finance industry, of which there are only three: Burford Litigation Capital Management and IMF Bentham, is that they offer the opportunity to invest in illiquid, hard to value assets, i.e. shares in the outcome of litigation cases, which have high returns on invested capital, but uncertain timing as to their resolution – much like illiquid/overlooked stocks. This may be why Burford trades on a relatively low P/E of ~9-10 before the share price fall, and currently 4.8x after it – it’s assets are hard to value. Therefore, although the company itself is not an illiquid stock – it has 115% turnover of its shares over the last year, based on 3 month average volume and 252 trading days, its assets are illiquid and hard to value. Therefore, it is possible to view Burford and other litigation finance companies, as the only way to access an illiquid and hard to understand pool of investments – the litigation finance market.

Environmental sustainability and social responsibility

Burford has a positive influence in the world in three ways: by deciding which litigation to support and which to avoid, investing in its people, and encouraging gender balance in litigation, by supporting women litigators.

Burford has a low number of staff, and very little few physical assets or footprint. Their main impact in terms of the environment, and also social responsibility comes in two forms: what litigation they choose to finance, and what to avoid, and secondly how they develop their staff. Firstly, they have stated that they aim to reduce environmental impact by locating their offices in very efficient and low-energy office space – their US offices are a LEED platinum building. In terms of social impact, they reject some investment opportunities if they could lead to small poor countries being forced to pay settlement fees, and they also make charitable contributions to law-related charities that campaign for more fairness in the UK and US legal systems, support objective research on social issues, and support a diverse set of stakeholders, to consider alternative solutions to social policy problems. Finally Burford launched a $50M Equity Fund, earmarked to support women litigators, and women-owned firms pursuing litigation, by providing alterative fee arrangements, to help redress the gender imbalance within law.

Risks – possible misjudgements

‘Fair value,’ valuation of assets is a subjective process; they could be overvalued.

The main risk is in the valuation of the assets of Burford Capital – 85% of the assets on the balance sheet ($1.43B of total $1.67B) are described as ‘level 3 assets.’ These are valued semi-annually by management, prior to the financial reporting period. Initially assets are added at cost to the balance sheet, and their value is only changed when there is a development, e.g. an offer of settlement, etc. The net change in fair value is reported as earnings, and in the last three years, has comprised between 57% and 65% of reported earnings. There is of course a significant amount of judgement required, in order to make these estimates. Given Burford’s summary of historical fair value results, for concluded investment in their recently released briefing report, historically speaking their fair value increases are conservative. The risk is that the quality of the judgements made by management deteriorates over time, and they overstate the value of their litigation investments – or that as the company expands and the current people who scrutinise it are forced to delegate some of their work, that they do not properly train and oversee the new people making these determinations. Currently, the fair value estimates and documentary evidence underlying these are presented to the independent auditors, and also to the board, which is entirely composed of non-executive directors. They are also all reviewed by the chief investment officer, Jonathan Molot who is also a 4.3% shareholder and so has a personal incentive to ensure the ongoing health of the company. Another related possible misjudgement is that of unrealised gains – this is equivalent to the total increase in fair value over the cost of making the investments. In 2018, unrealised gains were 39% of the total asset value, vs 22% in 2014. This increase is due to the period of strong growth in investments, and the typical weighed average two year lag between investment and recovery. This also means that Burford’s assets are 61% the cost of making the investment, and 39% the potential returns that have not yet been realised. In the past, e.g. the years 2009-2013, almost all of the fair value increases have been realised, except one case in 2010 where there is $107M of unrealised gains. (However, Burford has made profits for all these years, including 2010 solely based on realised gains). The risk is that the quality of investments might deteriorate, so that future fair value increases do not translate into realised gains. Burford is also changing the type of investments it makes over time – fewer of the core litigation finance, and more complex strategies and asset recovery type investments. Therefore, there is also a risk that they will not be able to value these investments, as well as they have been able to value the core litigation finance investments in the past.

Burford also reports on its concluded investments, how they were valued over time before realisation. Two years prior to realisation, they recognise fair value gains as 12% of the concluded (realised) value, and one year before they recognise fair value gains as 33% of the concluded (realised) value, e.g. if the conclusion is a $100M profit, two years before it is counted as a $12M fair value gain in the earnings, 1 year before it is counted as a $33-$12 = $21M fair value gain in the earnings, and in the year of conclusion, when $100M is received, it is counted as a $67M realised gain. The CFO stated in the capital markets webcast, that they use the most conservative accounting they are allowed to under the fair value IRFS rules, and this is borne out by these figures. This has been discussed in more detail earlier in the report as well, in the quality section.

A key part of the investment thesis is the continued ability of the company to grow, which rests on assumptions that the market is sufficiently large to allow this. At the moment, there is a clear trend towards litigation finance in the legal industry, but if this were to change, or if the industry were to become commoditised, this would present a problem. Burford describes that the current competitors are not competing aggressively on price. As the market grows, it is conceivable that a low-cost operator might enter and erode the margins. There are a number of reasons that this is difficult, e.g., Burford’s newest competitor is six years old, so the question must be asked: if this is going to happen, why has it not happened already? Possible reasons include the significant barriers to entry, i.e. cases require large commitments of money for periods of years, the investment time is uncertain and the return on individual cases is variable – all of these are features of an illiquid market. This makes it difficult for many large investors to enter this market. Due to the lumpy nature of returns, permanent capital is necessary, and returns are volatile, which is unattractive for many investors.

Another risk is that returns decrease – due to the nature of the cases Burford takes on, most of their profit is made from a few profitable cases. This means that their earnings may be volatile. For the total period 2012-2018, the coefficient of variation in their earnings was 52%, and for the period 2014-2018 it was 31%, showing that how much their earnings would decrease with a one standard deviation move down.

Conclusions

Illiquid stocks are often discounted relative to their intrinsic value by markets. This may be because investors cannot know when the market will revalue them close to the intrinsic value of their assets, and also because they may be infrequently valued/hard to value. In the case of Burford, the stock is not illiquid, but the assets it owns are, and also hard to value – their valuation depends to a large extent on subjective judgements of management. However, Burford has a track record of selecting litigation investments carefully, then realising their value over a number of years, being consistently profitable, and delivering a good return to shareholders. They are also the market leader, have good growth prospects, and several other advantages relative to their competitors.

Appraisal

Business value & fair multiple

Burford is very complex to appraise, and there is a significant element of judgement in how the appraisal should be conducted. Therefore, several different methodologies are demonstrated and the results compared. First, some assumptions which are common for all appraisals:

- No new equity/debt is issued. Due to the controversy surrounding the Muddy Waters short reports, Burford may find it more difficult than previously, to raise capital, so this assumption has been made as a worst scenario in this regard. Since only 8% of profit has been paid out as dividends in 2017 and 2018, it is assumed for simplicity’s sake that all profits are reinvested in the company.

- Given Burford’s slightly negative effective tax rate, no taxes are assumed to be payable or deducted from earnings, or tax credits added to them.

- Data source is the 2018 summary of each of Burford’s investments, covering the period 2009-2018, available from their website.

Appraisal methodology A: Cash return on capital employed

Figures for this appraisal were obtained from a document on Burford’s website listing every individual investment in their portfolio. The return on capital employed for the period 2009-2016 for Burford is calculated as follows: the cumulative cash profits of $349M on concluded investments, less cumulative total expenses of $131M (a 38% expense ratio), gives a profit of $218M after all capital deployed was repaid. The total capital invested into the business during this period, was $207M shareholders equity from shares issued, plus $131M of long term debt, gives $338M. Therefore, the total return on capital employed from 2009-2016 is $218M/$338M = 64%, and the annualised return on capital employed is 7%, for concluded investments – however this excludes the $220M invested at the end of the 2016 in ongoing investments. If this pays back in the weighed average of 1.8 years payback period for Burford’s investments at the same rate as the concluded investments, it would yield an additional 7%*1.8 = $88.2M, plus the original capital back of $220M, gives a total of $308M, minus expenses of 38%*$88M = $33M, gives $275M extra.

The cash return on capital employed is then $275M from the expected cash profits and return of capital, from ongoing investments, plus the cash profits from concluded investments of $217M, for a total of $492M profit on an investment of $338M, for 145% profit in the period 2009-2016, or 14% annualised. This avoids considering fair value, since a rate of return is calculated from the actual cash profits obtained, and then applied to ongoing investments to give a final rate of return on capital employed. Given that this rate of return excludes the original capital, and is net of expenses and taxes, it can be considered a ‘steady state,’ rate of return which the company could achieve without growth in its capital base. Therefore, these cash profits are available to either pay out to shareholders, or else reinvest in growth, or else repay long term debt.

Applying this same 14% annualised rate of return to 2018: the 2018 total asset value per share is $7.48, and the share price is $10, so the shares are priced at 10/7.48 = 1.33x total assets (investments and debt). Therefore, for a shareholder the cash return would be 14%/1.33 = 10.5% in a steady state, assuming that the current asset base is maintained, and no debt is repaid. This approach avoids using the ‘fair value,’ valuations provided by management. Excluding debt, net assets per share are $5.54, so shares are priced at 10/5.54 = 1.8 x net assets. 14%/1.8 = 8% cash return without leverage. This assumes no re-rating of the stock’s price : earnings ratio, currently ~5.2x.

This approach also excludes any growth from additional capital invested, e.g. from Burford’s fund management business.

Appraisal methodology B: Cash & fair value return on equity, without debt repayment.

The business may be valued by considering the total assets of Burford, and the likely returns on them, assuming a steady state where all returns are reinvested without additional capital being deployed. Using total assets assumes that debt is not increased or decreased over time, and no further debt/equity is raised. It can also be assumed that Burford’s tax rate is ~0%. At year end 2018, net assets are $1.2B.

Assuming that cash earnings in 2018 represent the conclusion of investments made in 2016, (since weighed average duration from investment to realisation is ~2 years) and taking the total assets in 2016 of $560M, the cash return on invested capital is 31% in 2018. Doing the same procedure for one year prior, it is 38%. If this is done for the past 7 years then an average 21% cash return on invested capital is obtained, two years after the capital is invested. Taking the more conservative number of 21%, in 2017, the total assets were about $1B, so a 21% return on this would give about $210M in realised cash earnings at year end 2019. If the fair value increase is 60% of earnings, then gross profit would be $525M. After subtracting 20% for operating expenses and interest payments, net profit would be $420M. There are 219M outstanding shares, so net profit/share would be 420/219 = $1.91. At the current share price of ~$10.00, this is a price:earnings ratio of 5.2x, compared with a historical average of about 15x for the FTSE-100 on the London Stock Exchange (LSE). Furthermore, Burford’s earnings have almost no tax, so this should add a further 25% to this ratio for a fair comparison with other stocks. Therefore a fair value would be (15/5.2)*1.25 = 3.6 x current price. Note that due to the two year lag between investment and return, the profits in 2020 and 2021 would be expected to be higher than in 2018, due to the large investments made in 2018 and 2019.

Another way to value Burford might be to consider what it might be worth in five years, without any additional debt/equity capital being added to the business: i.e. solely on growth of reinvested capital. This assumes that the price/earnings multiple does not change. Total assets in 2017 of $1.1B would be compounded at 21%/year to $4.7B in 2024. If earnings in year five (2024) are calculated from net assets in year 3 (2022) of $3.1B, at 21% this would be: $777M. If fair value represents 60% of earnings, then total earnings are ($777M/40)*100 = $1.9B. After subtracting 20% for operating expenses, net profit would be $1.5B, or 1500/219 = $7.10/share. If earnings today are $1.91/share, this would be 7.10/1.91 = 3.75x today’s value, for a compound rate of return over five years of 30%. However, the debt ($694M) would have stayed constant in this scenario so would be significantly smaller as a percentage of assets. It also assumes that the business continues to be valued on its current multiple of 5.23x earnings.

If the business multiple is re-rated to a P/E ratio of 10.5 (double current ratio) and growth occurs as predicted, then the business would be worth the re-rating (2x) and growth (3.75x) = 7.5x what it is priced at now, for a compound annual rate of return of 50%. This assumes that no additional debt capital is raised, so the business would also be significantly de-levered, i.e. debt to EBITDA ratio would decline from ~1.8x to ~0.5x.

Margin of safety:

If Burford was re-rated to be valued at 2/3 of the average FTSE-100 company, i.e. P/E ratio 10, the share price would be $10*(10/5.2) = $19.23, and then taking into account the 0% tax rate, it would be $19.23*(1+25%) = $24.03/share. Therefore margin of safety is: (24.03-10)/24.03 = 58%. This assumes no growth – but Burford has been growing strongly. Therefore, if it grows at 8% annually over the next five years – the most conservative scenario, which involves paying off all debt, and no new capital added, a final share price of $14.90 is to be expected, which if it were re-rated to P/E = 10, would be $28.65, for an annualised return of 23% over five years.

Disclosure: the author owns shares in Burford Capital at time of writing (October 2019).

About the author:

Dr Stephen Gamble enjoys investing, analysing complex problems, writing in depth about stocks, learning about business models, and finding out how industries work. He is also a PhD qualified chemist, who is currently working for a multinational company. He specialises in mapping intellectual property, identifying and developing new technologies and prototypes for respiratory protection products, and fault-finding and improving the stability and quality control of product testing and manufacturing processes. Prior to this, he did R&D in the fields of energy storage and developing new ceramic materials for fuel cells running on biogas.