Bonal (BONL): An Extremely Tiny, Extremely Illiquid Stock that Earns a Lot But Doesn’t Grow at All

Bonal isn’t worth my time. It might be worth your time. It depends on the size of your brokerage account and the extent of your patience.

So, why isn’t Bonal worth my time?

I manage accounts that invest in “overlooked” stocks. Bonal is certainly an overlooked stock. It has a market cap under $3 million and a float under $1 million (insiders own the rest of the company). It often trades no shares in a given day. When it does trade, the amounts bought and sold are sometimes in the hundreds of dollars – not the thousands of dollars – for the entire day. It’s also a “dark” stock. It doesn’t file with the SEC. However, it does provide annual reports for the years 2014 through 2018 on the investor relations page of its website. In the past, the stock has also been written up by value investing blogs. Most notable is the write-up by OTC Adventures (the author of that blog runs Alluvial Capital – sort of another “overlooked stock” fund). That post was written back in 2013. So, it includes financial data from 2008-2013. I strongly suggest you read OTC Adventure’s post on Bonal:

Bonal International: Boring Products and Amazing Margins – BONL

The company has also gotten some coverage in a local newspaper. For example, I’ve read articles discussing Bonal’s attempt to sell itself at a below market price. Shareholders rejected this. So, the stock isn’t a complete enigma. You have write-ups like OTC Adventures, you have some old press coverage, and you have annual reports (complete with letters to shareholders) on the company’s investor relations page. At the right price, it’s definitely an analyze-able and presumably invest-able stock.

But, not for me. Because I run managed accounts focused on overlooked stocks, I try never to eliminate a stock simply because it’s very, very small or trades almost no shares on most days. Even stocks that appear to have zero volume are sometimes investable. In my personal experience, I can point to cases where I bought up to 10,000 shares of a stock in a single trade that had a history of trading less than 500 shares on average. And that’s not a one-off fluke. It’s happened to me more than once. So, if the shares are out there – your best bet is to bid for the stock you like best regardless of what the past volume of that stock has been. Often, it may be easier to get into – and even out of a stock – in a few big trades than it appears on the surface. This is due in part to people trading much smaller amounts of the stock than you – and a few other bigger, or simply more concentrated investors – will want.

However, in the case of Bonal – there simply aren’t enough shares held by non-insiders to make it worth my while. The accounts I manage are not big. But, the investment strategy I practice is not one where you go out looking for 1% positions. It’s the kind of strategy where you always want to put 10% or more of the portfolio into any stock you buy. Sometimes, because of illiquidity – or the price moving up on you – the position size you end up with might be far short of 10%. But, to start bidding for something – you have to believe it’s possible to put 10% into this stock. Here, because of the extraordinarily small float, it’s just not possible. Even if everyone but the controlling family was willing to sell me shares – this would still end up being a smaller position than I want.

So, for me Bonal is a pass. But, those are trading concerns that some readers won’t have. Since I did look at the stock – I’m going to go ahead and write it up here without worrying about the fact that it’s “un-investable” for the accounts I manage. It might not be un-investable for your personal account. Maybe because your account is smaller. But, also maybe because you like to be much more diversified than I do. If you don’t mind single-digit percentage position sizes – maybe, Bonal is investable for you.

What jumped out to me about Bonal?

Two things. One, the company’s size and the fact it was often profitable. This is unusual. There are very, very few companies with sales of just a couple million dollars that manage to eke out a profit. Yes, there are some private companies – often, more like sole proprietor type businesses – that are consistently profitable on such a small level of sales. But, it’s extremely unusual to find a public company turning a profit at such low sales levels. This has important implications. It means the company must have strong product-level economics – gross profitability has to be amazing here – to allow anything to exceed the SG&A line. It also means that if the company can ever increase its sales by a few million dollars – the bottom line, the dividends paid, etc. are likely to absolutely explode.

Let’s talk “economies of scale”. The economies of scale gained by going from $2 million of sales to $10 million of sales are greater than the economies of scale gained by going from $2 billion of sales to $10 billion of sales. Investors underestimate this. We’re all used to using ratios, percentages, etc. to analyze the stocks we look at. This puts them on equal footing. It makes it appear that a group of 100 different wineries making 1,000 different wines has as good a chance of improving its operating margins as a company making 1 type of wine at a single vineyard. That’s wrong. The single vineyard has a much, much greater chance of expanding operating margins on even small increases in sales, because true fixed costs are a much greater percentage of the company’s current cost base and what I’ll call “semi-fixed costs” are also big. Semi-fixed costs are things that if the company quadrupled in size would be considered a “variable” cost because you would have to scale them up at the same rate. But, there is no scaling up of the cost – or very little scaling up of the cost – at small incremental sales gains till you hit a certain level of utilization. Basically, you might have a vineyard that could do $5 million in sales, but it is now doing just $2 million in sales. This doesn’t mean you need to more than double assets to get to $5 million in sales. It means you are operating inefficiently at 40% utilization of your current capacity. This is very, very common for very, very tiny companies. Everything about them from the premises they rent, to the sales team that markets their product, to the CEO’s time may be underutilized. The further down the income statement you go – the truer this is. Every company – even a “dark” company – has some “corporate costs” that eat up a lot of profit. It needs a CEO, it needs a board, and it needs an auditor. And every company – no matter how small – needs a location to use. Often, the location being used can handle more volume than a couple million in sales, production, etc. So, the administration of a very small public company and certain other general costs – as well as some costs that might end up in the “gross costs” line – have a ton of operating leverage built into them. Often, if sales go from $2.5 million to $1.25 million – the company goes from solidly profitable to being on the verge of bankruptcy. While a sales increase from $2.5 million to $5 million would make earnings explode.

Is that the case here with Bonal?

Well, the way to analyze that is to focus in on gross profitability. We’ll start with gross margins. For financial reporting purposes – which is the only thing we, as potential investors, are given a clear view of – gross profitability is a sort of stand-in for basic, variable profitability. A company with very, very low gross margins combined with very, very low sales turns (Sales / Assets) should always be incapable of earnings high returns on capital no matter how big it gets. There are some exceptions to this. A big brewery fully utilized probably has much lower unit costs than a small brewery mostly underutilized does. A production line being used intermittently to produce orders on a case-by-case basis might have super high gross costs compared to the same line being run 24/7 on stable demand. But, as investors, it’s very hard to see those things. Managers may understand the cost accounting and technical situation well enough to know that something with bad gross profitability today could actually achieve good gross profitability on 10 or 100 times the volume. But, we as outsider investors can rarely know this. What we can know is the financial accounting. We can know the gross profitability.

By the way, the reverse argument is easier to prove. Sometimes a small business with bad gross profitability might have a case to be made it can become a huge business with good gross profitability. But, the opposite is almost never true. Why would a company with high gross profitability on low volume ever become a company with low gross profitability on high volume? The only cases I can think of are very special ones like intentionally undersupplied high status or collectible products. Yes. If you are selling a bottle of wine for $150 – it’s unlikely you could increase production ten times and still maintain the $150 sales price, because the extreme rarity of the product on the low volumes you now produce is causing the perception of scarcity, high quality, a niche label, etc. that couldn’t be maintained if you produced more bottles and marketed them more widely. The scarce and hidden nature of the product may help gross margins. But, that’s just one example of the very, very few special cases where high gross profitability wouldn’t lead to higher and higher operating profitability when a small business scales up. In the vast majority of cases, a small business with gross margins that make early investors salivate will – if it ever grows – become a big business with operating margins that will make later investors bid up the share price.

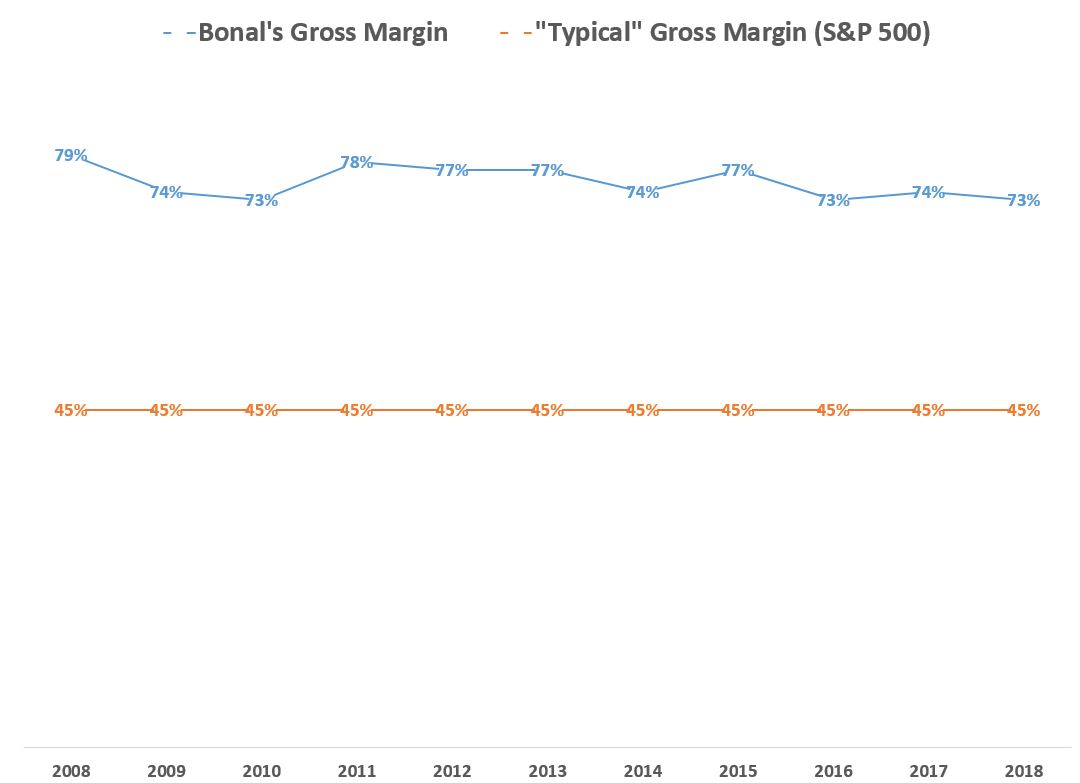

So, let’s take a look at Bonal’s gross margins.

Manufacturers often have lower gross margins than what I’ve used as a “typical” gross margin above. However, keep in mind that gross margins alone don’t matter much to a manufacturer. What matters is profitability. And profitability is always the product of margins AND turns. So, you need to look at both Sales/Assets and Profit/Sales to figure out the number you care most about: profit/assets.

Still, there can’t be a lot of price competition in a business that looks like this…

Gross Margins: 2008-2018

2008: 79%

2009: 74%

2010: 73%

2011: 78%

2012: 77%

2013: 77%

2014: 74%

2015: 77%

2016: 74%

2017: 73%

2018: 74%

The very low change in gross margins during the financial crisis, suggests that Bonal’s profitability isn’t constrained by how much it can charge (Gross Profit/Sales) – it’s more likely the company is constrained by a lack of orders. Orders – rather than prices – probably drop most in a bad year. You can judge orders somewhat – I haven’t done this here for you – by using the pre-markup figure of COGS/Assets. That’s “cost of goods sold” – NOT sales – divided by assets. So, it is turns on a cost rather than sales price basis. Why do that? A huge markup interferes with understanding the relationship between volume demanded and the willingness of a customer to pay a high price. If you look at gross margins and “cost NOT sales” turns, I think you’ll see that Bonal is unconstrained in terms of how much it can charge for what it makes – but, is quite constrained in terms of how much of what it makes it can actually sell at any price. Basically, this is a small niche that allows for a big price mark-up.

That’s an 11-year period. Luckily, it also includes the “bust” years of 2009-2010 (when the U.S. – and much of the rest of the world – was coming out of the 2008 financial crisis). Without knowing much about Bonal’s industry – about all I know is it sells to metalworking businesses – I’d say that period from 2008-2018 is a good test of what gross margins would like look under just about any economic circumstances. The company sells its products at more than a 70 cent per dollar gross profit and less than an 80 cent per dollar gross profit. Gross margins are 70-80%. To put this in perspective, 70 to 80% gross margins are equivalent to a 230% to 400% mark-up. In other words, if a widget costs the company $1 to produce – it’s turning around and pricing that widget at $3.30 to $5.

Of course, that’s misleading if sales volume in this line of business is so small that asset “turns” (Sales/Assets) are insufficient to earn an acceptable return on capital. Is that true here?

Because Bonal holds excess cash that is small in absolute terms – like $1 million – but gigantic in relation to the size of this firm (which does about $2 million a year in sales) I’ll base “turns” on stockholder’s equity less cash. This is a proxy for the amount of money owners have tied up in the business’s actual operations rather than just sitting idle in a corporate bank account.

Sales / Equity Less Cash

2013: 6x

2014: 6x

2015: 5x

2016: 4x

2017: 3x

2018: 4x

This translates into excellent cash returns on starting equity excluding cash:

2014: 28%

2015: 110%

2016: 7%

2017: 2%

2018: 23%

And merely “average-ish” cash returns on starting equity including cash:

2014: 8%

2015: 27%

2016: 7%

2017: 2%

2018: 23%

The above is somewhat unfair to BONL – as it’s likely that anyplace the company put its roughly $1 million in cash earned essentially zero interest in the period 2014-2018. If interest rates were several percentage points higher during that period and the company kept the same dividend policy in place – it might inch ever so much closer to a perfectly solid cash return on total starting equity (including idle cash) of more like 15%. The corporate tax rate cut in the U.S. can’t hurt either. So, while the record is for a very lumpy 13% cash return on starting book value – I could be persuaded to say the company is set up (even with idle cash) to generate more like a 15% after-tax cash return on its stated book value per share.

What is book value per share?

It’s 89 cents per share. So, at a stock price of 89 cents per share, Bonal would be a good buy…if and only if the company can deliver 10%+ cash returns on book value – that’d be equivalent to about 14 cents a share in annual cash earnings – at its current sales volume and would have much higher returns if sales grew at all, if it could re-invest a lot in its operating business, etc.

Unfortunately, the stock last traded at $1.40. That’s 1.57 times book value. Paying that kind of premium over book value would – if the company never disgorges its excess cash – bring down your total return in the stock to a less acceptable level. You don’t want to take any unusual risks – much less huge liquidity risk, the risk of owning a “dark” stock, etc. – to make less than 10% a year. You probably only want to take those kind of risks when you see a path to 15% a year type returns. Or, maybe when you have a lot of faith – like with a company reinvesting in its own growth – that 10%+ annual returns can be sustained for a particularly long holding period. Especially given today’s generally high stock prices, low bond yields, etc. – some might argue that buying into a solid, predictable stock at just a 10% expected annual return is the right decision. But, there are more solid, more predictable businesses than Bonal out there. Here, we have what amounts to a “silent partner” type investment – it’d be incredibly illiquid once you built a sizeable position in this stock – in a small business that promises to return just 10% a year. People buying into small business they don’t control definitely want to make more than 10% a year.

So, is Bonal a pass?

I can’t answer that one yet. Because there’s an easier way to value this stock. It is – perhaps – too aggressive a way of valuing it. But, the approach I used above is probably too conservative. After all, Bonal isn’t really a stock with 89 cents in book value. It’s more like a stock with 56 cents in cash and 33 cents invested in an absolutely amazing business (one that earns 18% to 34% after-tax cash returns on invested capital).

Let’s say the cash is worth the cash. In other words, the 56 cents in cash should be valued at exactly 56 cents. This reduces the stock’s “price” from $1.40 to 84 cents a share. Is Bonal’s operating business worth 84 cents a share?

There’s an easy way to check this. Bonal has paid a dividend every year for the last 13 years. The most recent dividend was 10 cents per share (for a 7% dividend yield on the $1.40 last trade price). And we know Bonal has not added debt, run down its cash balance, etc. over time. The operating business seems to be the source of funding for both the excess cash on the company’s balance sheet and the annual dividend paid to shareholders.

The most aggressive way to value Bonal would be to divide it into two buckets. The cash bucket is worth 56 cents per share (because the company has 56 cents per share in cash). The business bucket is worth the present value of 10 cents per share paid in dividends in perpetuity. At an 8% discount rate – basically, what we’d expect the S&P 500 to return if bought now and held forever – a perpetual dividend of 10 cents per share is worth $1.25. This is like saying the “cap rate” is 8%. In reality, I don’t think investors would capitalize a non-contractually obligated payment – this is a dividend paid at the discretion of the board, not the yield on a bond or a bank loan – at anything like 12.5 times. Nonetheless, the company could grow cash earnings. That’s not impossible.

Here we need to move into a bit of a theoretical “investment philosophy” type discussion. Let’s talk risk-adjusted discount rates. Whenever analysts, portfolio managers, CFOs, etc. talk about a company’s “cost of capital” or do a DCF or something – they talk about discount rates as if they should be used to capture the “risk” in a cash flow. This makes perfect sense for any cash flow with a hard cap on its possible return. For example, if I buy a 30-year investment grade corporate bond that yields 4.8% – I need to be thinking of part of that yield as being the result of the risk I’m taking. Right now, the 30-year U.S. Treasury yields 2.9%. So, here I’d be getting about 1.9% more per year – let’s call it 2% – to take the added risk in the corporate bond. We’ve matched the maturities of these two bonds here. So, we know it’s not reinvestment risk or something I’m taking here. These are also both nominal yields. Neither is inflation adjusted. So, we also know that this isn’t inflation risk I’m taking here. The added 2% a year I’m getting when I buy corporate long-term debt instead of government long-term debt is due to the “business risk” (the corporate credit risk) I’m assuming.

So, naturally, you can apply the same idea to common stocks.

Except you clearly can’t. I mean – you can do the math, and many people do. But, the exercise is flawed. It wouldn’t make sense to apply higher discount risks to “riskier” stocks because the risk of a stock with uncertain future earnings isn’t one-sided. In a stock, my potential dividend isn’t capped. See, as a bondholder, if I don’t know if a company’s earnings will rise by 50% next year or fall by 50% next year – I can take that as a single input in my analysis. The 50% rise doesn’t help me. It might make the bond be perceived as less risky and might give me a nice capital gain if I flip the bond in the next 12 months. But, as long as the bond keeps paying me my interest for these next 30 years and as long as the principal is repaid as scheduled – then, a 50% rise in earnings isn’t relevant to me. Only a 50% decline in earnings is relevant to me. So, a bondholder can afford to think of earnings volatility as being pretty close to the risk of not recouping some of my investment.

Common stocks don’t work that way. Think about it. A basket of micro-cap stocks bought at 15 times earnings certainly will have more earnings volatility than a basket of mega cap stocks bought at 15 times earnings. The price of the micro-cap stock basket will also be more volatile. A micro-cap stock fund is more likely to see a 50% decline in its NAV than a mega cap stock fund.

But, that’s the “trade” return in the two baskets. It’s not the “hold” return. In the case of bonds, we might ask: “Sure, the price of any basket of bonds will move around from year-to-year – but, what if I hold all these bonds till they mature?” That simplifies things from an exercise in predicting what “the crowd” will offer for my bonds in any given year and instead boils down a valuation of any set of bonds into just the question of credit risk. Sure, there’s reinvestment risk and inflation risk and all that – but, we can use things like the U.S. Treasury to benchmark those levels.

We can really say that the 2% I get paid in the corporate bond over the government bond with the same maturity date, is the discount in the price of the corporate bond (that is, the premium in the yield of the corporate bond) to compensate me for this risk. So, it becomes a simple question of a trade-off between a perfectly safe 2.9% a year or a somewhat less safe 4.8% a year. I evaluate that trade-off and I choose the corporate bond or the government bond depending on how much more yield I’m getting for how little risk I’m taking or vice versa.

In other words, a corporate bond is only going to outperform a government bond if I buy it at a higher yield.

Is that true of common stocks?

Of course not. You can make more money in stocks with the same dividend yield, same P/E ratio, etc. as other stocks. How can you do this?

If the “coupon” grows faster in one set of stocks than in the other.

This presents a really big problem for the idea of using a higher discount rate to value small stocks with unstable dividends versus large stocks with stable dividends. What if the odds actually favor the small stocks growing their dividends faster than the big stocks?

More importantly for stock pickers like us – what if you could have more actionable information about the odds in a small stock than a big stock. This isn’t as crazy as it sounds. Starbucks (SBUX) will definitely have less earnings volatility than Bonal. But, Starbucks is also likely to have more information about likely future dividends priced into the stock than Bonal is. Using a higher discount rate for more volatile dividends is equivalent to assuming you have no way of knowing better than the crowd whether the long-term volatility in the stock’s dividend – the trend – will be towards growth or decay.

For example, Bonal paid a 15 cent dividend in 2016, a 4 cent dividend in 2017, and a 10 cent dividend this year. Any of those 3 dividend levels could be the “normal” level to expect over the next many decades.

Because we know Bonal has excess cash and I also know – though I haven’t discussed it with you here – that cap-ex at Bonal is almost always non-existent, we can use EPS as a good proxy for dividend paying power.

Here is the 11-year EPS history at Bonal.

2008: 30 cents

2009: 2 cents

2010: Nil

2011: 29 cents

2012: 19 cents

2013: 13 cents

2014: 8 cents

2015: 25 cents

2016: 12 cents

2017: 3 cents

2018: 16 cents

The 11-year average is 14 cents. The stock last traded at $1.40 a share. So, if Bonal’s future looks like its 11-year past and it pays out all earnings in dividends – you’d expect a 10% dividend yield on today’s stock price (not a 7% yield). By the way, on a free cash flow basis – the expected dividend would be also be exactly 14 cents a share. There is close to zero difference – over an 11-year cumulative record – of any difference between reported earnings and “cash” earnings. So, that’s still a 10% dividend yield on today’s stock price.

So, we have a stock here that – based on its 11-year past record – is probably priced to yield anywhere from 7% to 10% a year. If we use the past 11 years of free cash flow per share – or reported EPS – as our guide, the expected dividend yield would be 10%.

But wait. Bonal’s tax rate has changed. Changes in a company’s tax rate are difficult to perfectly model from a microeconomic perspective. Depending on the bargaining power of the business, the asset intensity, etc. a corporate tax cut can vary from 100% retained by the company’s shareholders all the way down to 0% retained by the company’s shareholders (passed on to customers, suppliers, lenders, employees, etc.). Bonal checks all the boxes from the kind of business that would experience the biggest boost from a corporate tax cut. It has extraordinary pricing power. And it makes minimal capital expenditures.

However, the company’s actual tax rate paid in the past seems quite low. There is some information on certain tax benefits that reduce the rate actually paid. As a result, I would guess that Bonal might pay a bit less in taxes – and, therefore, have more after-tax cash to pay shareholders – but, I’m unwilling to attempt a precise calculation. I can’t see how it would pay more in taxes than before the corporate tax cut. Therefore, I would say that – if Bonal produces the same pre-tax earnings over the next 11 years as it did over the past 11 years – the stock should be capable of yielding more than 10% a year on its last trade price of $1.40 a share. Basically, I’m saying this is a stock that can pay an average dividend of 15 cents a share going forward.

So, taxes aren’t a question worth spending much time thinking about here. The more important question is to judge which way earnings volatility might occur. At Bonal, gross margins are both extraordinarily high and extraordinarily stable. As a result, the volatility in the company’s earnings comes entirely from the physical volume of its output. Basically, it is sales volatility not sales profitability that matters at Bonal. If we knew what the company’s future sales would be – we could know whether this stock is a risky high dividend yield stock – or, a super cheap stock that might pay a lot more out in future dividends than anyone expects.

Unfortunately, the company’s sales are a lot more volatile than its margins.

Sales: 2008-2018

2008: $2.5 million

2009: $1.7 million

2010: $1.8 million

2011: $2.6 million

2012: $2.3 million

2013: $2.5 million

2014: $2.1 million

2015: $2.4 million

2016: $2.1 million

2017: $1.6 million

2018: $2.3 million

For one thing, you can see there is no clear sales growth trend there at all. Luckily, there’s also no noticeable sales decay either. Those are nominal figures. But, inflation has been quite low over the last 11 years. So, it’s impossible to find any trend in either nominal or real sales there. The company looks like it should have about the same “earnings power” – as Ben Graham likes to call it – in 2019 as it did in 2008.

Again, this points to a stock that can be split into two buckets.

The “cash bucket”: $0.56/share

The “dividend bucket”: $0.15/share per year

Now, we could easily estimate what those things should be worth. In theory, cash should be worth cash. So, 56 cents a share. And the average expected dividend should be capitalized at the expected return on the S&P 500 from this point forward. Let’s call that 8% a year. Well, $0.15 divided by 0.08 equals $1.88/share. We sum the two buckets and get $2.44 a share.

Do I really think Bonal is worth $2.44 a share?

It last traded at $1.40 a share. So, that kind of appraisal would put the stock at a 57% price/appraisal value ratio.

I think – without being able to predict how likely it is the company can grow sales – that I would say Bonal is not worth more than $2.44 a share. Let’s call $2.50 a share a hard cap on the upside here. I could imagine that a 100% acquirer with plans to allocate capital differently, better insight into the business than I have, etc. might not lose money acquiring this thing at a price as high as $2.50 a share. I could see someone paying that much for the whole company and being able to look back on the decision and say it wasn’t an error.

Would I pay that price?

No. And, honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if the family was happy to sell out at a much lower price than that. Years ago, they planned – presumably this was the former Chairman’s idea – to sell the company at a fraction of that value (86 cents a share back in 2013). I actually don’t know the history of that offer and the family’s disagreements about it. I assume there was some sort of disagreement within the family on whether or not to take the deal (after all, the deal was rejected). And the new Chairman – while a family member – is not the same Chairman under whom that merger was planned. So, it’s the same controlling family. But, it might not be a good idea to use a rejected offer from 8 years ago as the basis on which to value the company today (especially with a different Chairman).

Because I don’t know anything about the actual background of the attempt to take the company private – all any blog post, comment, newspaper article, etc. I’ve ever seen is using as a source is the company’s own press release – I don’t want to speculate too much on what happened. But, I will say there is some slightly misleading information in the little bit I’ve read where other investors talk about that going private attempt.

One thing always mentioned about this offer is that it must have been a going private transaction where the family tried to force out the non-family minority shareholders (folks like you and me) at a below market price.

You can still find the press releases – they are at OTCMarkets.com under the “BONL” news tab – that include the original letter of intent announcement (where the company claims a majority of shares were held by shareholders who agreed to the deal), the amended letter of intent (which amends the original deal from an offer to buy a majority of the company from selling shareholders – named as mostly family members and family trusts – to an offer to buy the ENTIRE company), and finally the acceptance of that merger by the board (sort of – I’ll get to the sort of in a second).

This last part is important. In the press release announcing a merger – so, this would force the outside shareholders to sell if a majority supported the deal (unlike the original offer, which presumably was just an offer to buy the family’s stake in Bonal) – some other events occurred:

“Separately, Thomas E. Hebel and Paul Y. Hebel have resigned from the board of directors of Bonal International, Inc. The company’s board of directors has also relieved Thomas E. Hebel from his duties as acting Interim President. Mr. Hebel remains an employee of the company, serving as the Vice-President of Marketing. Mr. A. George Hebel III, past president and chief executive officer and current chairman of the board of directors, has been appointed Interim President, effective immediately.”

Note the use of the word “separately” and not “unrelated”. Two family members resigned when the merger was agreed to. And the board relieved one “Thomas E. Hebel” from a job they had – when accepting the original letter of intent to buy a majority – not all – shares of the company, specifically requested stay on in that position.

Why is this important?

A few things. First, we know Thomas Hebel resigned as a director and left – was “relieved” but quite possibly after he resigned as a director (which is kind of like firing someone after they quit) – as interim President. Two, A. George Hebel III is the one who replaced him. Well, “A. George Hebel” died the next year. And he was replaced by “Thomas E. Hebel”. George Hebel was Chairman from 1992 to 2010. It looks like he attempted to sell the company in 2012 through 2013. Then, he died in 2014. Meanwhile –Thomas E. Hebel resigned during the attempt to sell the company and then took over in 2014 (after his George died). Thomas E. Hebel is the Chairman who writes all of the annual letters from 2014-2018 you can read on the company’s website. We have no reason to believe that the current Chairman (Thomas E. Hebel) supported the idea of selling the company, forcing out non-family shareholders at a below market price, etc. And we have some evidence that he didn’t support the idea of selling the company (he’s very clearly NOT listed in the original announcement where the majority of shares were to be sold – in fact, all that’s said about him in that press release is that he “has been asked to stay with the company”). We also have very strong evidence he definitely opposed the merger that would sell the entire company: he resigned from the board and was relieved as interim president the same moment the merger was announced. He was re-appointed to the board (as was Paul Hebel) about six months after the merger was rejected. Because he’s not named among the original selling shareholders, is mentioned as being “asked to stay with the company”, then left as both a director and as President of the company at the same time the merger was announced, the merger failed, then he returned to the board after the merger’s failure, and finally he took over the company again from his (I assume) brother – I think it’s misleading to say that the current management of this company tried to push out minority shareholders at a below market price. Actually – as best I can tell – the current management seems to have actively opposed the attempt to sell the company. That’s very different.

Okay. Let’s really get into the weeds of Hebel family speculation here.

Because of the way some people are referred to – I’m not 100% sure that I know the family connections between board members. My assumption – which could be very wrong – is that Gus Hebel was the founder and George, Thomas, and Paul were sons of his. George was Chairman from 1992 to 2010. Then he retired leaving his (my best guess is) brother, Thomas, as President. George then tried to sell the company in 2012. Paul (again, I think, George’s brother) is listed as a seller in the original plan for a buyer to acquire majority control of – but not actually merge with – Bonal. Thomas was never listed as a seller. Then, when the offer changed to a merger – which would include buying out minority shareholders – indications are that George still supported the merger, but that both his (again, I’m guessing) brother Paul and his (guessing again) brother Thomas opposed the deal (since we know they both resigned). Since then: Thomas and Paul rejoined the board. George died. Thomas is the current Chairman & CEO.

I went into all this about separating George from Thomas from Paul for a good reason. We talk about “the Hebel family” wanting to sell the company in 2012 at a terrible deal for outsiders and now “the same Hebel family” running the company in 2019. But, I did just explain that George tried to do the merger and then both Thomas and Paul resigned from the board and the shareholder vote failed.

Today: Bonal lists its board members, their positions with the company, etc. in the back of their annual report. Remember, the two Hebel family members we know resigned the same moment that merger was announced are…

Thomas E. Hebel: Current Chairman, President, and CEO

Paul Y. Hebel: Current Vice Chairman

So, the Chairman & CEO and the Vice Chairman are the two Hebel family members who resigned over that bad merger offer. We don’t know a lot here. But, I think it mischaracterizes the situation to say that the people currently in control of this company tried to swindle outside shareholders. Actually, the two top people on this board resigned in some sort of intra-family dispute over that unfair deal.

With a family controlled, dark stock like this – any sale process of a company is very murky. For example, nothing is said about the merger being voted down except that because the motion failed at the meeting – negotiations with the buyer were terminated. We can know very little for sure without talking to someone connected to the family. So, I don’t want to say that you should or shouldn’t have confidence that the current Chairman is especially shareholder friendly or not.

But, I will say that based on the press releases I read – the idea that the current management tried to force a “take under” on outside shareholders is false. We have no evidence of that. In fact, we have quite a lot of circumstantial evidence against it. And the family member we most clearly do know tried to sell the company is dead. So, we really can’t say there’s a high likelihood of outside shareholders being abused here going forward. The opportunity to abuse outside shareholders is high. There’s no doubt of that. But, that’s true at any dark, family controlled company.

There’s a very high risk of a family controlled, tiny company running things with only the family in mind. You have to accept that if you’re going to buy a stock like this. But, that’s about all I see for sure here.

Okay. So, I think the price at which the family planned to sell the company – at 86 cents plus a 20 to 30 cent dividend (so, $1.06 to $1.16) back in late 2012 – is not especially useful. But, we’ll note it as one indicator of value. In late 2012: there was a deal struck to sell the company at $1.06 to $1.16 a share. You’ll hear some people say it was an 86 cent a share offer. However, that’s incorrect. The company planned to pay a 20 to 30 cent dividend before the sale and then another 86 cents when the deal closed. That adds up to a $1.06 to $1.16 offer in late 2012.

We know what some of the family was willing to sell at – and a buyer was willing to buy at – in 2012.

But, what price would I pay in 2019?

Again, there’s a fairly simple way to answer that question. Let’s assume I want some sort of “compartmented defense” here. In other words, I want a value redundancy where one compartment of my intrinsic value “ship” can flood and yet the stock can stay afloat above the price I paid.

The way to do this is look at cash per share as first thing keeping the stock price afloat and look at the likely dividend per share as the second thing keeping the stock afloat.

Imagine there’s no dividend. Can the stock stay afloat at $0.56/share? Sure. They have that much cash. In most years, the business is profitable on an earnings and free cash flow basis. So, yes. It shouldn’t trade below cash per share. Bonal should stay above 56 cents a share as long as it has more than 56 cents a share in cash.

Now, let’s perform the reverse exercise. Imagine there is a dividend. But, imagine there’s no longer any cash on that balance sheet. It gets blown on a bad acquisition, etc. Of course, it could be used in a way that doesn’t just destroy 56 cents per share in value. In theory, you could buy something money losing. Remember, we’re talking about only $1 million in cash. So, I’m not sure what you could really buy with that. It seems more likely the cash is worth something between 56 cents a share (they pay it all out as a special dividend tomorrow) and zero cents a share (it never earnings interest, is never paid out in dividends – etc. It just sits there forever and ever). I’m comfortable using that range. The worst case scenario is that cash is worth nothing. The best case scenario is that it’s worth 56 cents a share. For valuing the “dividend compartment” alone – let’s assume the cash already on the balance sheet is worth nothing. But, that the company will continue to pay dividends as it has for the last 13 years in a row.

Okay. So, what kind of stock price can be supported by the dividend alone?

Well, at this moment: the highest potentially sustainable dividend yield I know of among U.S. public companies is 9.4% a year. The company that pays that dividend is National CineMedia (NCMI). I’m not going to get into the details of NCMI here except to say it’s a company with a market cap over $1.2 billion and highly leveraged (with debt between 4 and 5 times EBITDA). The company’s EBITDA is very safe (it basically has 18-year contractually guaranteed rights to sell ads on movie screens right before the previews start) – but, the high leverage means the dividends to investors are less secure. Moody’s rates the company’s bonds “non-investment grade”. And the dividends obviously sit behind the bonds. The company’s policy is to literally keep almost no cash on hand (all cash is basically pushed out of the company every single quarter). This is a good comparison in the sense that a completely unleveraged business that has paid dividends for 13 straight years, has not lost meaningful amounts of money in any of those 13 years, has virtually no liabilities, and keeps several years’ worth of dividends on its balance sheet at all times shouldn’t have a higher dividend yield than National CineMedia. That’d be crazy. Bonal’s dividend yield should always be equal to or less than NCMI’s. Never more than.

Okay. So, we said NCMI yields 9.4% right now. For the sake of simplicity, let’s round that up to 10%. And then we can just capitalize Bonal’s likely average future dividend at 10 times. That’s the stock price it is “safe” to pay based on the dividend alone.

I have dividend per share data for Bonal from 2012 through 2018. Here are those dividends.

2012: $0.14

2013: $0.30

2014: $0.05

2015: $0.20

2016: $0.15

2017: $0.04

2018: $0.10

That’s a range of 4 cents to 30 cents per share. The average is 14 cents a share. If you capitalize 14 cents per share at 10 times you get $1.40 a share. That’s the share price level I’d say is supported by the likely future dividend yield alone – assuming no meaningful future earnings growth, no use of the already existing cash pile, etc. In reality, because of the tax cut – you’d have to say the likely future dividend is probably no less than 15 cents per share and the stock price supported by the likely future dividend alone is $1.50 a share.

Because Bonal doesn’t trade frequently – there’s often a bid/ask spread. For example, as I write this…

Last trade = $1.40

Highest Bid = $1.38

Lowest Ask = $1.72

To be sure you get shares right away – you’d need to bid $1.72 a share. Obviously, don’t do that.

In this case, the highest bid is close enough to the last trade that the last trade is a good enough proxy for what you should actually bid. Logically, you’d either bid $1.39 a share (topping the $1.38 a share highest bid) right now – or, you’d put in a bigger order at a much lower bid. It’s possible someone wanting to sell quite a lot of shares might sell them to you below $1.38 a share, because you’d be bidding for a lot more shares than whoever if bidding $1.38. In all honesty, that’s what I usually do in illiquid stocks. I start by making a pretty big volume bid at a lower than “market” price. There’s no reason to believe that the current bid/ask is necessarily indicative of where the stock would sell “on heavy volume”.

You’ve gotten this far. Now, the question is: should you bid for shares of Bonal?

Well, normally, I’d stop my “initial interest post” right here. Later, I’d write a follow-up post where I discuss the business, its durability, its future growth prospects, etc.

We’ve already covered everything that “initially” interested me in Bonal. It’s a dividend payer that – based on past experience – might already be yielding 10% a year for long-term buy and hold shareholders who get in today and average something like a 15 cent dividend over their holding period in the stock. It’s also got more than a third of its market price in cash on the balance sheet. Liabilities are close to nil. And the company’s gross profitability is truly extraordinary.

That’s all I’d need to know that “yes, I’m initially interested” in Bonal.

However, I started this article by telling you I’d probably pass on Bonal simply because there isn’t enough “float” to make buying it for the managed accounts an investment that could possible “move the needle”. Bonal is such a small stock – that we can all get a taste of the “Warren Buffett problem” here. Warren Buffett’s problem – managing a $100 billion+ stock portfolio – is that he can mostly only consider $100 billion+ market cap companies. And you certainly can’t invest meaningful amounts of his portfolio in any sub $10 billion market cap stock. He has to focus on stocks with over $100 billion market caps. And he can’t afford to waste even a second consider stocks below $10 billion (these could never be more than 1% positions for him).

That’s my problem here with Bonal. So, I’m pretty sure this is a stock I will never follow-up on. Despite that, some of you might be diversified enough in your personal accounts for Bonal to be a potential investment. It’d still have to be an incredibly illiquid investment. But, hey, if it’s going to yield 10% while you hold it – you can afford to get in with no idea if you could ever get out. You could just buy this thing and hold it indefinitely. So, it will be worth some readers’ time.

Therefore, I’ll wrap this up with a brief discussion of the business Bonal is in.

Bonal describes itself as:

“…the world’s leading provider of sub-harmonic vibratory metal stress relief technology and the manufacturer of Meta-Lax stress relieving, Black Magic Distort on Control and Pulse Puddle Arc Welding equipment. Headquartered in Royal Oak, Michigan, Bonal also provides a complete variety of consulting, training, program design and metal stress relief services to several industries including: automotive, aerospace, shipbuilding, machine tool, plastic molding and die casting, to mention a few. Bonal’s patented products and services are sold throughout the U.S. and in over 61 foreign countries.”

What does that really mean? We know from other parts of annual reports – which I’m not going to quote here, you can read them yourself (none run more than a few pages) – that Meta-Lax is used in a variety of metalworking applications. The company’s founder and his son (who later went on to run the business) were co-inventors of the technology. The first Meta-Lax patent was in 1971. All I can tell from reading about the technology is that it’s an alternative to the “heat trace method” of stress relief.

What about the way this technology is monetized?

Sales to “machine and fabrication shops” were 50% of last year’s sales. Aerospace was 12%. The company has sold in 60 countries overall. But, it only sold in 12 different countries last year. So, customers are machine shops. Three years ago, repeat customers accounted for 42% of sales. Two years ago, repeat customers accounted for 54% of sales. And, this past year, they accounted for 63% of sales. Given how high gross margins are at Bonal – even this most recent year’s figures are actually a surprisingly low rate of repeat customer purchases. It’s much more common for a business selling spare parts, doing repairs, servicing an existing installed base, etc. to have high gross margins than it is for a company that sells to a lot of brand new customers each year.

The demand for Meta-Lax has to be really, really low. So, what is Meta-Lax?

We know its equipment that is sold to metalworking companies. The equipment’s supposed benefits are to “control machining and welding distortion, improve product quality, and increase service life”.

In a past shareholder letter, the CEO wrote:

“Yet our loyal Bonal customer base, not only ordered more Meta-Lax equipment, they also referred and required their suppliers to use our Meta-Lax technology. Companies that invested in Meta-Lax equipment this year overwhelmingly selected our top model for its capability to graphically certify stress relief results.”

So, we know a lot of the sales are for the company’s top model. And we know the top model is some sort of metalworking equipment that can “graphically certify stress relief results.”

The company’s sales are probably done in pretty large part through trade shows. A letter to shareholders mentions trade shows. And based on my very limited knowledge of private companies that have a just a few million dollars in sales (despite selling globally) of capital equipment – trade shows are a common way of getting on the radar of new customers.

In addition to machining and welding – Bonal mentions customers in the die casting, mining, and motorsports industries. Two customers mentioned by name are TigerCat (forestry equipment) and Bombardier (airplanes).

How much of sales are foreign and how much domestic? I assume most are domestic. Bonal doesn’t break this out each year. However, when they did mention it – they gave a breakdown of 20% to 25% foreign and 75% to 80% U.S. Also, when the company mentions countries they sell to (and, I’m generalizing because they have sold this equipment in 60 countries) – they seem to share certain economic traits with the U.S. manufacturing sector. Basically, they’re Northern European countries and such. Also supporting the “mostly pretty domestic” argument here is that Bonal did say in one annual report that Canada is the company’s biggest source of foreign sales. That suggests a very North American centric business. Globally, Canada’s a pretty big economy. But, if Canada is your second biggest market – you’re probably a very U.S. focused company. And when Bonal talked about trade shows it only mentioned shows in the U.S. and U.K. On the other hand, the equipment’s specs do say it can run on like 5 other languages besides English.

The company mentions – in its 2016 annual report – a specific model. It’s the model 2800. I haven’t found images of that. But, I have seen images of series 2000, 2400, 2700, etc. You can find these by visiting the company’s website or doing text or image Google searches.

For a description of the Meta-Lax technology, you can visit this page of the company’s website:

http://www.bonal.com/tech/tech.html

All I can tell you is that Bonal’s equipment is meant to relieve thermal stress. As you can see on that page, the technology is named as a combination of “metal” and “relaxation”. Since I don’t know anything about welding, etc. – this information isn’t very helpful to me. For example, why is this process so rarely used (if the $2 million a years in Bonal’s sales worldwide are any indication)? Are there very niche applications that find this technology beneficial? A couple times, Bonal mentions aerospace customers and things like that. But, it seems that half of sales are coming for much more general customers (though, I don’t know if those customers are using the equipment for very specific jobs or more generally). Saying that a customer is a “machine shop” isn’t really helpful in knowing the actual way in which that customer is using the Meta-Lax equipment. We know the customers are metalworkers. But, we don’t know how small a part of their overall business is done using anything Bonal sells.

Obviously, Bonal touts its own technology. The argument it makes in favor of Meta-Lax is:

“Meta-Lax continues to achieve the same effectiveness and consistency as heat treat stress relief yet without the expense, time delays, huge energy consumption, and the many other negative side effects that are common with the heat treat method.”

Since I don’t know anything about metalworking – all this really tells me is that Bonal’s sub-harmonic vibration approach is an alternative to the standard heat treat method. But, which is better for what applications? That’s way outside my circle of competence. And it’s dangerous to base any conclusions on what the company that markets the technology is telling you. This would be an area where you might be able to do some scuttlebutt – especially if you know anything about metalworking.

If you look at images of Bonal’s equipment – it seems we’re really talking about different iterations in the same product line. The company said – back in 2015 – that 80% of revenue was from equipment sales. So, you can probably guess that about 80% of the company’s sales are for whatever images you can pull up for “Meta-Lax” equipment (this is the series 2000-whatever stuff I’m talking about).

In Bonal’s 2014 letter to shareholders, there is a little more information about the founding of the company and the creation of its Meta-Lax technology:

“…the founder of Bonal…was the owner of a machine shop. He knew that the metalworking industry needed a low-cost and energy-efficient method of stress relief that was as consistent as the traditional, but expensive, heat-treat stress relief method. Gus made it his mission to fill that need. Gus created the Meta-Lax process and, building on its initial success, continued to improve and perfect the process as Bonal Technologies introduced 14 stress-relief models. In 1988, the U.S. Department of Energy took notice and, following their own research, began to promote Meta-Lax as an energy savings invention, showing that Meta-Lax stress relief was 98% more energy efficient than the traditional heat-treat method. When Bonal became a public company in 1990…Gus became its first chairman of the board.”

So, what’s the conclusion here?

Bonal is basically a one tech and one product line – the equipment based on this tech – company. It’s mostly a domestic company. So, it’s probably tied more than anything else to U.S. machine shops. The technology is an alternative that the company believes is superior to the traditional – and presumably, more commonly used to this day – method.

Is this a good technology that has just been under marketed by the inventor and his family?

Or, is there some reason it will never be widely adopted?

I don’t know the answer to that. It’s entirely possible this is perfectly good technology, equipment, etc. But, this is a really small company. It can’t spend on R&D, marketing, etc. the way a big company does. It’s entirely possible that the marketing done by this company is not as sophisticated at what bigger, public companies do.

So, this may never be a growth story. But, if the technology is solid – which I have no way of knowing one way or the other – then, this company could be solid.

Bonal is a $1.40 a share stock with more than 50 cents a share in cash and the potential to pay more than a 10% dividend yield in the future. The fact that Bonal does not follow a policy of paying the exact same regular dividend each year – but, instead, pays a lot one year and then a little the next as business ebbs and flows cyclically could actually be a huge blessing for long-term investors. If this thing had a history of paying 15 cents a share in dividends for 10 straight years – it’d never be this cheap. Because dividends are lumpy – they’re may be a chance to buy stock in Bonal in low dividend per share year and then hold those shares indefinitely.

Due to the extreme illiquidity here – you have to view any investment in Bonal as being a permanent investment. Whatever shares you are successful in buying should be seen as forming a “permanent position” in the stock. Basically, this stock is so small and so illiquid that you have to take the Warren Buffett approach if you want to invest in this. This is truly a buy and hold forever situation. In some future year – you might get to sell it with a nice capital gain. But, that can’t be part of the investment case for buying it today. This investment has to work as a buy and hold forever stock. With the potential to have a 10% dividend yield on today’s price – the math here works as a buy and hold forever investment.

If Bonal had a bigger supply of “share float” – I’d definitely be 100% sure this is a stock I’d follow up on. And, odds are, it’d be a stock I’d actually buy for the managed accounts.

Because I like more concentrated positions – and this thing is simply too small to “move the needle” for the accounts I manage, I’m undecided about whether to follow up on it or consider buying whatever teensy amount I can get for the managed accounts.

As a result, I’m going to give Bonal an “initial interest level” of just 50%. I’m sure it’s an interesting stock. I’m just not sure it’s worth my time given the miniscule float.

Bonal last reported earnings on February 15th. The company’s sales – over the last 9 months – are down 30%. Earnings are down more like 90%. If you look at Bonal’s long-term history, this kind of thing does happen. Year-to-year variation in sales and earnings is big. So, I’d still focus on the long-term average earnings per share, dividend per share, etc. when looking at this stock. Paying a low price relative to the average EPS, DPS, etc. of the last 10 years or so seems the right approach here. A bad year for earnings might be a good year to buy the stock. I’m not sure if that’s the case this year. But, in the last 12 months, Bonal’s stock price has probably dropped about in line with the sales decline.

Geoff’s Initial Interest: 50%