Games Workshop (GAW): The Wide Moat, Formerly Mismanaged Company Behind “Warhammer 40,000” Has Always Had Great IP And Now Finally Has the Right Strategy

WRITE-UP BY PHILIP HUTCHINSON

Overview

Games Workshop Group plc (“GAW” or “GW”) – which trades in London under the ticker “GAW” – is by far and away the dominant publisher of tabletop wargames and designer, producer and retailer of miniatures used in those wargames. The company itself would describe its business as the design, production and sale of model soldiers that serve the “hobby” of collecting, modelling, painting and gaming with model soldiers. This is strictly true, but does not do justice to the company’s products. This is because the “model soldiers” are based on the belligerents in the company’s two major fantasy settings, Warhammer Age of Sigmar (fantasy) and Warhammer 40,000 (science fiction).

It’s easiest to demonstrate this visually, with a photo of one of the miniatures from Games Workshop’s range:

This miniature is a Primaris Space Marine. Space Marines are GW’s single most iconic creations – armies of elite, genetically engineered superhumans wearing power armour and dedicated to defending humanity in a hostile galaxy filled with forces bent on humanity’s destruction. The full GW model range is simply vast though, which you can get an idea of by visiting the company’s web pages at www.games-workshop.com, www.warhammer-community.com and www.forgeworld.com. The key point here is that GW’s “model soldiers” have much more in common with the kind of thing you’d find in a sci-fi franchise like Star Trek, Star Wars, or Alien, than they do with real life.

This miniature is a Primaris Space Marine. Space Marines are GW’s single most iconic creations – armies of elite, genetically engineered superhumans wearing power armour and dedicated to defending humanity in a hostile galaxy filled with forces bent on humanity’s destruction. The full GW model range is simply vast though, which you can get an idea of by visiting the company’s web pages at www.games-workshop.com, www.warhammer-community.com and www.forgeworld.com. The key point here is that GW’s “model soldiers” have much more in common with the kind of thing you’d find in a sci-fi franchise like Star Trek, Star Wars, or Alien, than they do with real life.

You should understand that if you went and bought the model above (or any of GW’s range), they would come unassembled and unpainted. (The model above was assembled and painted by a member of GW’s design studio.) Assembling and painting the models are key parts of the hobby. The other key part is using those models in tabletop wargames for which GW publishes and maintains rulesets.

GW earns revenue from selling models (such as those above – though its full range is absolutely vast), modelling tools, paints, boxed games, rules books and rules supplements, gaming accessories such as dice and templates, and scenery, all for games set in its two main fantasy settings. Sales are made through GW’s network of company stores, independent stockists, and online. GW also licences its IP to third parties to earn royalty income. The main source of royalty income is for video games set in GW’s fantasy settings. In addition, GW has a publishing arm that earns revenue from publishing novels and other fiction set in the Warhammer and Warhammer 40k universes.

The key thing to understand is that GW services the all-encompassing hobby of collecting, assembling, painting and then wargaming with miniature soldiers. There are no direct quoted peers. This is because GW is by far the biggest company in its industry. It dominates the industry the same way Tandy Leather Factory dominates leathercrafting (arguably more so, as GW is a global business). There are some peer companies out there – companies like Privateer, Battlefront, and Mantic. But they’re much, much smaller than GW and also (this is a crucial difference) unlike GW they do not have a large network of company owned stores. We’ll go into further detail about GW’s business (including its scale relative to competitors) below. But, if you’re unfamiliar with it, think of the company as a bit like a video game publisher but whose games are tangible, rather than digital, and where most of the profit comes not from the sale of the game (which, in GW’s case, is often a boxed set containing rules, dice, other accessories and a starter set of models for two opposing factions) but from additional books, miniatures and accessories that hobbyists use to build armies and expand their collections. Really – the best peer (not competitor, but useful as a comparison to aid understanding) is probably Nintendo. Nintendo’s IP has a very different feel – GW’s is much darker, more violent and more sinister. But GW is selling a closed system of miniature wargames based on proprietary IP, just as Nintendo sells a closed system of video games based on proprietary IP. (In the same vein, an indirect peer might be something like Disney. This is relevant because GW has a large back catalogue, of miniatures, books and games systems.) And, incidentally, the close link between GW and video games publishers is illustrated by the fact that one of the company’s founders, Ian Livingstone, went on to found his own video game publisher which ended up becoming part of EIDOS Interactive (now owned by Square Enix), publisher of videogames such as Tomb Raider.

GW is absolutely dominant in its industry. It’s also one of the oldest companies in the industry. It was founded in 1975 in London and shortly thereafter moved its HQ to Nottingham, England, where it remains to this day. Initially it was a retailer of board games published or produced by other companies – things like backgammon and mancala – and got started down the road to its current business model by becoming a UK distributor for Dungeons and Dragons. In this period the company also started its monthly magazine, White Dwarf (still published today), and gradually started moving towards being a publisher of its own games (and manufacturer of accompanying miniatures) rather than a distributor, as well as starting to establish the first stores in what has become a very significant company owned store network, particularly in its home market in the UK. Eventually, GW transitioned fully to only publishing its own games and selling its own miniatures, set in its two key settings of Warhammer (fantasy) and Warhammer 40,000 (science fiction).

For our analysis, we can split GW’s history into a few different eras:

- 1975 – 1991: the early years in which the company’s strategy gradually shifted towards the closed system

- 1992 – 1994: the first years of the closed system, culminating in going public in 1994

- 1994 – 2004: the “early Kirby era” – fast growth phase

- 2005 – 2016: the “late Kirby era” – losing its way post the Lord of the Rings bubble

- 2017 onwards: the “post Kirby era” – more customer-focused company again on the path of growth?

The first two periods are of marginal interest in assessing the business today. We should really concentrate on the period from 1994 – 2004, the struggles from 2005 – 2016, and the company’s significant recovery in the last two years.

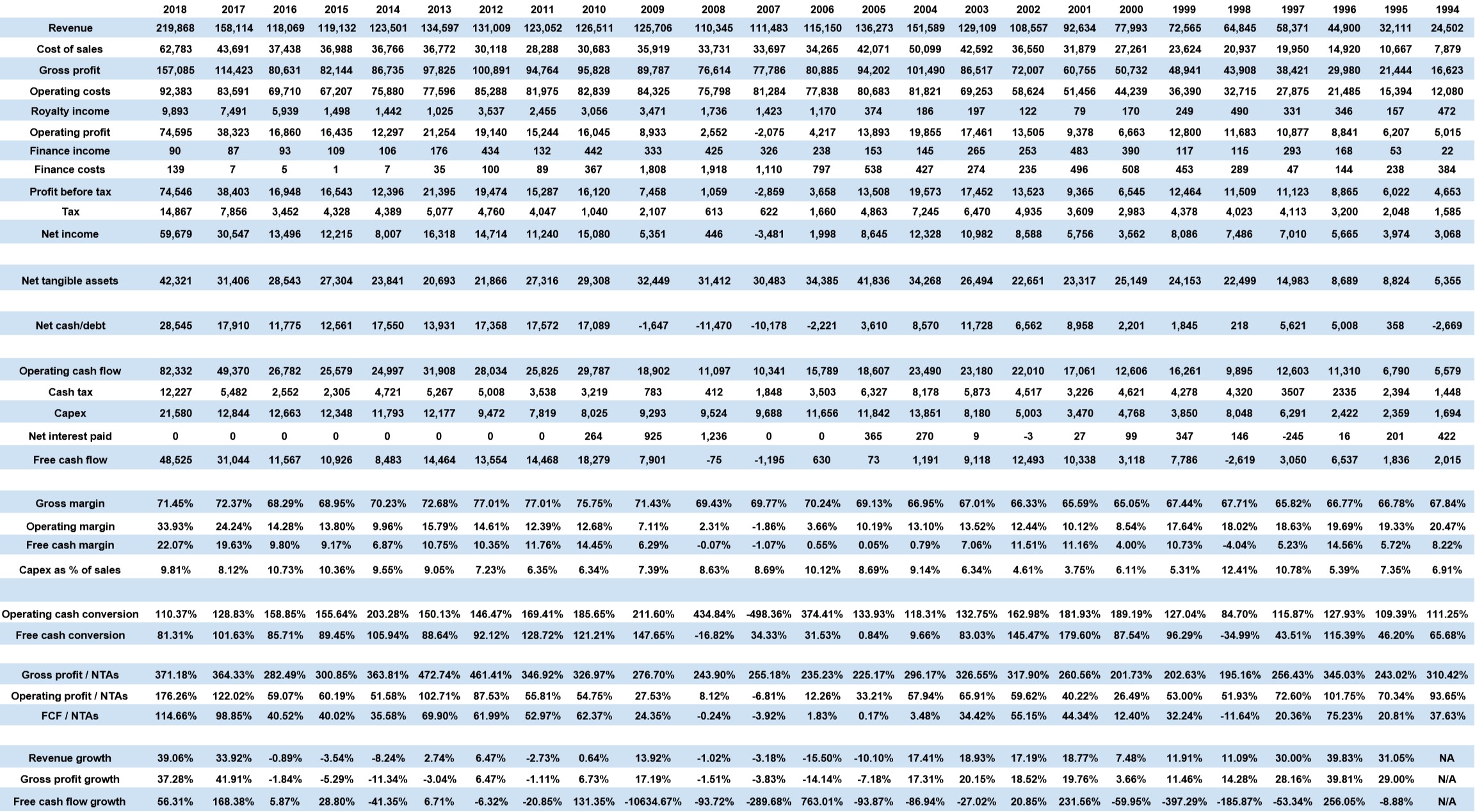

What I’ve termed the early Kirby era is essentially the first half of Tom Kirby’s stewardship of the business. Kirby is a very important figure in GW’s history. He was a key part of the MBO that led to the company going public in 1994. He became a very significant shareholder in the company. And he was chairman and / or CEO for many years. The early Kirby era was one of fast growth. From 1994 to 2004, revenue grew from £24.5m to £151.6m, i.e. a CAGR of just under 20%. And this was profitable growth. GW didn’t routinely disclose same store sales, but this growth came from expansion of the store network in the UK, international expansion, growing the mail order business, and same store sales growth. The later years, from 2001 – 2004, also benefitted from GW producing under licence Lord of the Rings games and miniatures to coincide with the Lord of the Rings film releases.

The late Kirby era, 2005 – 2016, saw the business lose its way. Sales in 2016 were £118m – over 20% below the 2004 peak. The business did remain cash generative, and paid a dividend, in most of those years. But it was clearly struggling. Gross margin remained stable, never dropping below 66%, but operating margins ranged from an operating loss to a high of 15.8%. The period was (unsurprisingly) accompanied by management changes – Kirby stepping down as CEO to become Chairman, and then unexpectedly returning as CEO while remaining Chairman – and changes of operational structure. It was also a period of increasingly narrow product focus, creative entropy and intense frustration among the customer base.

2017 onwards represents the post Kirby era. Tom Kirby has now ceased to have board or managerial input. He remains a significant shareholder, though he has recently sold a lot of shares. The business is now run by long time GW veteran Kevin Rountree. And the upturn in its fortunes has been remarkable. Sales grew by 34% in 2017, and then by another 39% in 2018. Gross margin was over 70% in both years, and operating margin ballooned to previously unheard-of levels, reaching 34% in 2018. This demonstrates the significant latent operational gearing in the business, as sales increased markedly on a relatively fixed cost base, that had in any case been cut during a store rationalisation and cost reduction programme. This financial growth was accompanied by significant creative growth, with a faster pace of new product releases, very significant narrative developments to the two main fictional settings, and releases of new (and remade versions of old) games.

This highlights the key investment question for Games Workshop stock. Is the recent sales growth a temporary flare, similar to the early 2000s Lord of the Rings-induced growth? Or, is it a return to trend as the company re-engages with its customer base following a lost decade? If it’s the former, the stock will do badly from here. And if it’s the latter, it should do ok even at relatively pedestrian growth of say 4 – 5%, and will do really well at anything above that.

Durability

The business of selling miniature wargaming products is a durable one. Miniature wargaming itself (as distinct from highly abstract games like chess, or board games like Monopoly or Settlers of Catan) has a history going back well over 100 years. The miniature wargaming industry, comprised of companies such as GW, Battlefront, Privateer Press and Mantic, is much younger. But even then, the markets for both fantasy and historical wargames and miniatures is several decades old.

Over the last 25 or so years, there have often been questions about whether video games will supplant miniature wargaming, or turn it into an even smaller niche, as potential (and current) customers dedicate their time exclusively to video games. In reality, there appears to be little likelihood of this. That is despite there being numerous games that are squarely within the same niches – in terms of content – as GW’s games. Obvious examples would be games like Halo, World of Warcraft, and Call of Duty.

GW’s customers definitely play video games. Maybe if there weren’t any video games, they’d buy more GW product. But it’s not possible to find any obvious effect on GW from the increasing popularity of video games – either now or in the past. The likely reason is that GW (and miniature wargaming in general) is sufficiently distinct from video gaming that neither is a true substitute for the other. The two categories do compete for the time, attention and money of potential customers. But only in the sense that TV and video also compete for that time, attention and money.

There are aspects of miniature wargaming that video gaming cannot really recreate (and the converse is, of course, also true). First – the tangible nature of the product. This is inherently appealing but also provides an outlet for creativity in imagining, building and then painting miniatures. Miniature wargaming has essentially infinite possibilities even within the bounds of GW’s own settings. Secondly, the game playing experience using physical, tangible models and playing opponents “in the flesh”. This gives an entirely different (not necessarily better or worse) competitive experience. For similar reasons, board games remain popular in the video game era. Third (and this is relevant for Moat and Quality) the existence of a large, distinct community (both gaming and modelling) for competition, peer aid and feedback, discussion, and socialising.

Finally, there is the fact that GW has some really unique IP. This is subjective. But, the Warhammer 40,000 setting, in particular, is one of the richest, most distinctive, recognisable and iconic sci-fi backdrops there is. In a similar way to Star Trek or Star Wars, a huge fictional history has built up over the decades. (And like both of those franchises, the individual quality of each novel, story, piece of artwork, plot, etc, is hugely variable. A lot of it is, frankly, awful. But the best 40k is, in my view, as good as or better than the best Star Trek and Star Wars. And the average quality probably isn’t any worse either.) There’s a good argument that the 40K IP is under-exploited commercially, and that that should change over the medium to long term. So, even if there is a secular downturn in miniature wargaming, it seems to me that GW is well placed – certainly much better placed than its competitors – to survive and find new ways to exploit its IP.

Overall, GW has above average durability.

Moat

GW is one of the widest moat businesses I’ve ever come across. There are multiple aspects of GW’s business that work together to create this moat. But, really, much of it comes down to the fact that GW’s products are addictive. That’s figurative. Obviously they’re not addictive in a medical sense. But they are addictive in the sense that long-time GW customers have very, very deep attachment to the product, aren’t really price sensitive, and will always buy more product if the product is good and the price is not really excessive.

Getting into more detail, there are a number of factors that all operate together to give GW a really, really wide moat. They can be put into two broad categories. First, relative scale. And secondly, immersive IP.

Relative scale

GW’s relative scale is quite extreme. We can’t be certain about it, because GW’s direct competitors aren’t public. But GW had 2018 revenue of £220m. Estimates are hard to come by, but peers such as Privateer have revenues in the $5 – $10m range. Battlefront (which dominates historical – World War II – miniature wargaming) is probably a fair bit bigger than that. It’s a New Zealand company that doesn’t have to disclose its financials. But, I’d estimate it may be three or four times the size of Privateer. So it could be a $40m revenue company. That’s still smaller – a lot smaller – than GW. And this relative scale has two particularly important implications – one for product quality, and one that is a sort of network effect.

First, product quality. Although it is an IP driven company, the bulk of GW’s sales and profits come from the sale of miniatures. Miniatures are manufactured products. So, being the biggest company in the industry by far means that GW can have effective scale in production for a much larger range of models. GW can invest more in design and production per miniature, far deeper into a far bigger range of models. And it can also keep up a higher pace of new releases (because it employs more designers, sculptors, and production staff.) To understand this, it’s helpful to know that miniatures can be made from three main materials – metal, resin and plastic – each of which has different characteristics both from a production and a customer standpoint. While this is subjective, as a generalisation it’s fair to say that, for a customer, plastic is the best material, then resin, and then metal (some would debate the ordering, particularly of the last two). However, the initial investment required to create a plastic mold is high. I’ve seen estimates that for a single frame of plastic miniatures the cost can easily get into six figures. That was some time ago and it seems that the cost has come down in recent years so that it’s more possible for smaller companies to produce miniatures using plastic. But either way – it’s undoubtedly far more expensive in terms of initial investment. On the other hand, once the mold is created, the production cost per miniature is much lower. This is where relative scale becomes very important. GW, by virtue of its vastly greater size relative to competitors, can have a much higher percentage of a much bigger model range made out of plastic. It can make more complicated, large, highly posable models. It can, therefore, have a bigger range of higher average quality that it can produce more cheaply than competitors. This is a dramatic, and quite likely permanent, competitive advantage. (There is a counter argument that the falling cost of production of plastic models means this competitive advantage will erode over time.)

That’s just model production. This relative size advantage also extends to choice, product range and quality from a gaming perspective, and the depth the company can bring to its IP. Those areas are arguably at least as important as model quality.

Then there’s the network effect. Miniature wargaming is a hobby with a worldwide community. But you also need a local community for the hobby to work – because you need people to play games with in person on a regular basis. Well, the worldwide community that collects WAOS and 40K is simply much bigger than that of any of its competitors. So for example, even if I want to collect and play Flames of War (Battlefront’s flagship product), I have to find an opponent to play, and preferably several. It’s quite obvious that, as this is a game that is played in person, the system with the most players is very well placed to win long term. That’s just because it’s the one you’re most likely to actually be able to play regularly. Something similar also applies to the modelling side – the system with the most players, the biggest painting competitions, etc, will attract the most customers. The most popular systems belong to GW. And GW don’t have to have the best product here. There have been times when competitors clearly had better games systems, in terms of ease of playability, balance, logic, etc. Customers complained for years about the flaws in the 40K game rules, yet it is still (I estimate) by far the most popular miniature wargame out of all the games that are played with miniatures that require assembly and painting. The advantages of having the largest player base are basically like being a software company with a large installed base or a network with the most users. It’s really difficult for individual customers to switch to a competitor unless they all do so en masse. And the customer base is a large group of individuals that do not act coherently in an organised manner. So, GW are still on top. And all they have to do is have a system that’s adequate – particularly if (which has not always been the case) they are seen as responsive to player concerns.

Adding to this network effect is GW’s company owned stores. There were 489 company owned stores at the end of the 2018 financial year – of which 144 were in the U.K., 134 in North America, and 148 in continental Europe, with the balance in Australia and Asia. These stores obviously only stock GW product. And they don’t just serve as shops. They have gaming and painting tables set up and host games, painting competitions and other events – i.e. they’re effectively a local wargaming and modelling club, nurturing the local GW community. They also act as marketing and customer acquisition tools, and staff have a big focus on introducing what can seem an arcane, overwhelming hobby to new customers in a friendly, welcoming way. This is a big competitive advantage for GW, as none of its rivals have any sort of company owned store network. This aspect of GW’s moat is unevenly distributed. It’s very strong in the UK, where GW largely built its business by rolling out a nationwide store network. It’s less strong in other jurisdictions where sales through independent stockists are more important.

So, on the relative scale side, GW has a moat based on:

- Higher product quality

- Wider product range

- Bigger customer network

- Large base of company owned stores.

The second part to GW’s moat is customers’ emotional attachment to its products. This is a little more vague and subjective, but no less real or important. It may even be more important than the scale-related aspects of GW’s moat. While this element is relevant to customer acquisition, it’s probably more relevant to customer retention.

The key things to understand here are probably the enormous depth of the company’s IP, and the creative aspect of the hobby. These two things work together very powerfully to create a very deep moat around established customers. The Warhammer 40,000 and (to a lesser extent) WAOS settings now have decades of content – in terms of art, miniatures, rules, novels and other fiction. It’s of very variable quality, obviously. But the settings are no less immersive – and maybe more so – than other well-known science fiction or fantasy settings. It’s this aspect of GW’s business that is similar to a studio such as Disney, and also is an aspect of its business model that is better than a video games publisher, because GW has a longer lived, more durable back catalogue.

To illustrate this depth, let’s look at Warhammer 40,000. The action takes place in the 41st millennium (hence the name). But over recent years, GW has been exploring in depth – through art, novels, models and rules – the fictional history of Warhammer 40,000, going in depth into the events of 10,000 years earlier, a civil war known as the Horus Heresy which set the scene for a long running conflict (dubbed the “long war” by the forces of Horus) between the Imperium of man and the traitors who sided with Horus to try to destroy it. Clearly, that level of depth and richness of background takes years to develop.

And then there’s what customers actually do. That ties into the rich and evocative background in an important way. What they do is spend lots of money, but more importantly lots of time – hours and hours – creating and painting their miniatures, and then using those miniatures in games where they will inevitably, over time, do particularly dramatic things (whether heroic or inept). So, it’s easy to see how customers develop quite personal and emotional attachments to their favoured factions, characters and miniatures. It’s hard not to do so when you’ve put so much time, energy and effort into creating miniatures and imbuing them with personality. Lots of customers would identify as (for example) an Ork player, a Tyranid player, a collector of Space Wolves Space Marines, and so on. GW has a big advantage here over competitors (Battlefront primarily) whose games are historical, rather than fictional – e.g. set in World War II – because the fictional setting means that GW and its customers have greater creative freedom and no historical baggage. That leads to deeper emotional ties.

It’s easy to go online and see evidence of this emotional attachment. Much of the huge amount of online commentary on GW is critical of the company. Some of this criticism is fair, some less so, but nearly all of it is borne of deep attachment – addiction – to the company’s products.

And the result of this is that, although few people in the world are really interested in GW’s products, those who are end up being very valuable customers. GW is not a subscription business, so it doesn’t measure retention rate (at least, not publicly). But the lifetime value of a customer must be very, very high. These customers aren’t monogamous. They will play other miniature wargames – and also video games, board games, and so on. But if GW puts out product that appeals to them, they will buy it. And – while GW does not have unlimited pricing power – a 5, 10, or even 20% price cut by a competitor is unlikely to tempt someone away. It’s not a comparison shopping business at all in that way. After all – if, for example, you want to own a maniple of Battle Titans from the Legio Astorum “Warp Runners” Titan Legion (and I do), then GW is your only possible supplier, and you’ve no choice but to pay the price they ask.

Quality

GW has above average business quality.

The core product economics of the business are excellent – and also stable. The lowest gross margin going back to 1994 is 65%. And the gross margin has generally been in the high 60s or low 70s. This is for a company that produces manufactured product, so this sort of gross margin is exceptional. The company can generally increase prices at or above inflation. It undoubtedly has pricing power.

Operating margins have been more variable. In some years (e.g. 2007) there have been operating losses. But, generally, the business has been profitable or very profitable.

And returns are generally high. In good, or even merely average, years operating profit as a percentage of net tangible assets is high, often over 50%. GW does lease properties, which flatters returns a bit, but not a lot. Clearly, returns are more than adequate.

It is generally cash generative as well. Growth has been self-funded, the company pays out substantial dividends, and it usually has solid cash conversion. Cash flow will pretty much always lag accounting profit at GW, because – as a publishing business – it capitalises some development costs. It’s safer and more realistic to view those capitalised development costs as simply part of the business’s ongoing cost base (still not entirely realistic, as some of those costs are likely to be funding the company’s growth. So, we’re punishing the business a bit by doing this, but probably not a lot). So, free cash flow – averaged out to address year to year variance – is certainly a better yardstick of owner earnings than accounting profit.

The really important question is how sustainable the excellent results (and much better margins) of the last two years really are.

Capital Allocation

GW has simple – if slightly unorthodox – capital allocation.

Capital allocation is 100% dictated by the company’s practice of paying out 100% of “truly surplus cash” (their phrase) as dividends. GW is unlikely to make any acquisitions (to my knowledge it’s only made one in its entire history, and that was tiny). It’s also unlikely to take on any debt. In the past it has bought back shares, but that was a long time ago and there’s no sign of it doing so again. So, it will invest in its business to the extent required – although, even allowing for capitalised development costs, it’s really not asset heavy – and pay out any free cash flow above and beyond its reinvestment needs. That means a variable, unpredictable, but usually substantial dividend.

Growth

Growth is important at GW because, without it, returns in the stock will be middling at best. It’s also hard to judge because the recent (post-2004) record is so variable.

We certainly should not expect growth to continue at the rates of the last two years. Interestingly, though, if we take 2018 sales as our end point and go back to 1994 as our starting point, the long term (24 year) rate of sales growth is 10% per year. So, viewed over the longer term, the company’s growth rate looks very much more sustainable, and it appears plausible that the rapid growth of 2017 and 2018 is simply the company catching up with its long term trend (by doing no more than the basics of re-engaging with its customer base and reinjecting creative zest into the design studio – following a lost decade of a moribund, stagnating outlook and a complete misdiagnosis by Tom Kirby of what makes the business tick).

As noted above, GW clearly has pricing power. It should be able to pass inflation directly through to customers. So, if the company can just grow its customer base by 1 – 2% per year, it should be able to manage a growth rate of 5% a year (say 3% inflation, 2% net customer base growth). And growing the customer base by 2% a year seems a pretty modest goal to me – one that I would be confident of hitting if I were GW’s CEO. First, there’s the possibility that GW should over time be able to achieve sales per capita in big countries (primarily the U.S. and Germany – both countries where it is well established already) that move closer to what it achieves in the UK. It’s unlikely U.S. or German per capita sales will ever reach parity with UK sales, because GW’s UK store base means it’s almost certain to have higher penetration in the UK than in other markets. But the gap should close somewhat. That alone would probably exceed a 1 – 2% growth in the customer base.

And then, GW’s industry should gradually be expandable worldwide over time (this has of course already happened to a significant degree). GW’s products cross national boundaries fairly well. The miniature wargaming community is both local (in terms of regular play) and national / global (in terms of online communities, tournaments, and competitions). So, there should be a modest annual contribution to growth from increased international penetration. Given the very high lifetime value of truly established customers this is potentially a very significant source of long term value.

And more speculatively, there’s the possibility for increased royalty income (and more generally increased income from finding other ways to monetise GW’s IP, outside of the miniature wargame industry). This is inherently difficult to predict. But, as mentioned earlier, GW’s IP is really rich and deep. It’s also underexploited. For example – GW should have been capable of partnering with a video games publisher to produce something like (but better than) World of Warcraft. That was a huge missed opportunity. Licensing revenue is already an important profit contributor. Over time, I’d expect that to grow, possibly significantly, though it’s hard – maybe impossible – to say how consistently or how much. Nonetheless, surprises should be to the upside here rather than the downside.

Overall I think it’s difficult to see growth at GW as likely to be less than nominal GDP. And it could be more – potentially a lot more. Part of my confidence here comes from my view that Tom Kirby got two really important things wrong in the latter half of his time as CEO that the new CEO is not getting wrong.

First, he took something that was true about the company’s business – that all the profit was made from the sale of miniatures rather than rulebooks and boxed games (the boxed games are like starter sets) – and made the mistake of thinking that therefore all the company’s energy should be directed at making increasingly intricate, set piece miniatures, rather than developing the rules, the narrative about the background setting, new games, expansions for the games, or generally engaging with and promoting the gaming side of the hobby. It’s a bit like if Nintendo were to say that they make all their profit from the sale of games, so they stopped concentrating on developing new consoles. Or if Disney said that the big profit from something like Frozen comes from the sale of merchandise. So, let’s concentrate on making more and more intricate merchandise rather than coming up with more new hits. Basically, yes, the profit comes from the sale of miniatures. But what drives customer behaviour (and therefore sales of miniatures) is as much about development of the games and the narrative as it is about creating new and interesting miniatures. Neglecting that was really harmful to the company because it infuriated customers and also led to creative stagnation in the design studio.

Secondly, Kirby had a healthy disdain for management consultants and marketing professionals. That was probably wise. GW has never used traditional advertising. It’s always marketed itself via word of mouth and via its store presence. I think that is a good decision given the nature of the product. Traditional advertising would probably attract the wrong kind of customer and harm the company’s reputation. But he seemed to take this to an extreme and encourage a really disdainful attitude towards customers. Basically, customers were there to have product thrust upon them whether they were interested in it or not. No attempt was made to work out what customers wanted, what they liked or didn’t like, or what they wanted to see the company do next. For a company where the customer base is so deeply attached to the product, this is particularly bizarre.

The new CEO has basically reversed all those practices. So, he’s encouraged the design studio to put out a lot of new innovative content – new games, new miniatures and new narrative developments.

And, the company has built trust and engagement with its customers via social media (Facebook, YouTube, etc) and its own website. We’re not talking anything innovative here, really – just the basics of engaging with your customers and fans using modern media. But this has really turned things around. If you go on any of the fan websites you’ll still find complaints and criticism. That is inevitable in a creative business like this. But it’s very different to what it would have been a few years ago. And just subjectively, the company is now releasing far more products that I would be interested in than it was in the last decade of Kirby’s period in charge.

So, growth is definitely the most speculative bit of the investment case for Games Workshop. But there are still good reasons to think that the company should be able to grow at a reasonable rate.

Misjudgment

The key risk of misjudgement with GW is that the return to growth of the last two years is transient. If that turns out to be the case, buying GW shares will be an expensive mistake. The company has a bigger cost base than its peers (due to its hundreds of company operated stores) and is trading at a price to sales ratio that is high relative to its history (though its price to earnings and price to free cash flow, while high compared to past years, are not so elevated, because the recent growth has led to material margin improvement).

Ultimately, this is a qualitative assessment. If this risk does materialise, there could be a few reasons for it. For example – the company could struggle to recruit new customers in the face of competition from video games, smartphones, and other miniature wargaming competitors. That is a risk that the company has always faced. It’s a real risk, albeit not one that has done any serious damage yet. Or (and more likely in my view), the company could be lulled back into incompetence and abuse of its customers by virtue of its strong position. That is my theory as to what happened from say 2003 onwards. The company was so absurdly disdainful of its customer base, so almost wilfully misguided as to what customers wanted and how its business really worked. Most businesses would have been destroyed by that level of incompetence and it was only the huge emotional ties and customer loyalty of GW’s customer base that let this persist for so long. Other businesses would have been forced to change course earlier or go bust. GW survived – at the cost of a lost decade – but significant long term damage was nonetheless done; long term customers lost forever (an unforgiveable sin given the huge customer lifetime value and difficulty of customer acquisition in this business), and of course the growth of dangerous competitors such as Battlefront.

If GW can grow sales at or above 5% on a consistent basis, the stock will do well. So the risk is largely one of misjudging either growth or competitive position.

There is another risk. Royalty income is currently at a historically high level of sales and is a material contributor to operating profit. I’ve discussed the possibility of growth in royalty and other sources of IP derived income. But it could trend down to lower levels. This is a difficult bit of the business to make predictions about, but if royalty income dropped by 50 – 75%, which is not impossible, then that could easily knock 20% or so off the stock price overnight.

Value

Price to free cash flow (or maybe EV / Sales, assuming a normalised free cash flow margin) is the best way to value GW. It removes the risk of over valuing the company by not accounting for capitalised development costs. Given GW usually has modest net cash, using either EV or market cap is probably fine and unlikely to make much material difference.

The problem is entirely in accounting for a normalised level of free cash flow. The free cash margin has essentially doubled to 20%. If things go well at GW I think there is the potential for this to actually get to 25 – 30%. This is mainly because, as far as I can tell, GW’s manufacturing facilities could accommodate higher volume without material capex – and the costs of the development studio should not be materially greater for sales of £300m than they were when the company’s sales were £150m. Then, any increase in royalty income is pure profit. Together, those factors will tend to increase margin.

I’m certainly not going to count on that, but equally there is no reason to think that, if the current sales volume is maintained, margins will drop. So, I will value GW on the basis of a 20% free cash margin. The average company is probably worth at least 15x earnings, equating to 20x free cash flow. That means GW is worth an EV / Sales multiple of 4.

Sales in 2018 were £220m (it looks likely they will be around £240m in 2019). So the company is worth an EV of £880m.

If you are prepared to use forecasts and estimate that 2019 sales will be £240m then that rises to £960m.

GW has net cash of £28m and a market cap of £1.428 billion. So, an EV of £1.4 billion. So the company is quite expensive right now, at over 5x sales.

But prices change a lot. The shares were trading at around £28 earlier this year.

So, for now, the company is a pass. But if it gets to less than an EV / sales of 4x, I think it would be a buy.