GAP Inc. (GPS): A Market Leader in Apparel Retail Is Spinning Off Underperforming Assets Which Should Drive Shareholder Value, But Income Derived From a Third-Party Credit Card Agreement Overstates The Company’s Earning Power And Makes the Stock Too Risky

Write-Up by Jonathan Danielson

Gap Inc. (GPS) is a company everyone should be familiar with: they’re an apparel retailer that specializes in ‘casual classics’. Meaning, jeans, khakis, polos, button downs, etc. The Company is headquartered in San Francisco and was founded in 1969. Gap Inc. has acquired and launched several brands over the years, but its main ones currently are: Old Navy, Gap Brand, Banana Republic, Intermix, and Athleta. GPS has increasingly become an Old Navy company over the years as consumers have flocked towards value brands and have deserted higher end specialty brands so it wasn’t too terribly surprising when they announced at the end of last quarter their intentions of separating into two companies. Interestingly enough, Old Navy will be the RemainingCo operating as a stand-alone business while Gap Brand, Banana Republic, Athleta, and Intermix will be spun off.

Based on consolidated metrics, GPS appears to be an interesting situation. When I pull the company up on QuickFS.net I see a company that has 10 year averages of:

- Gross margins: 38%

- EBIT margins: 11%

- ROE: 29%

- ROIC: 34%

All for a P/E of 10 and an EV/EBITDA of 6-ish. Not bad for a retailer. In fact, I was expecting much, much worse. If you pull almost any of their peers up and measure them on the same metrics you get an entirely different picture. More specifically, I looked at Guess, American Eagle, and Abercrombie and Fitch. Let’s just say when you pull those company’s financials up it looks like they have been existing in an era where questions are being raised about the viability of the brick and mortar retail business models. So, perhaps there’s an interesting situation here after all. Gap Inc. only grew revenue at a 1.8% CAGR over the past 10 years. However these are consolidated numbers and Old Navy is being spun off, remember? And Old Navy has been growing faster than the rest of Gap. Inc’s brands. Additionally, the “peers” I listed above most likely aren’t peers – not for Old Navy at least. The companies I previously listed are closer to Gap Brand and Banana Republic. The closest peer for Old Navy is probably somewhere in between Ross and H&M. Ross has been able to maintain healthy margins and growth while it appears H&M has struggled of late. Nonetheless, both companies look much healthier than any of the specialty-type brands previously listed.

We might have a compelling thesis on our hands if Old Navy is all that management cracks it up to be. The answer, as typically the case, isn’t so clear as one would hope. After all, GPS is operating in an environment that’s been dubbed the retail apocalypse. We’re living in the age of Amazon, how is your classical brick and mortar retailer churning out 34% returns on capital? Is Old Navy really that good? Well, I have my suspicions that it might not be the case. I’ll walk you through the numbers, show you how great of a business management tells us Old Navy is, and why I think it most likely is not all sunshine and rainbows over there in SF.

Why the Spin?

But first, we have to discuss the reason we’re all here – the Spin-Off. The reason that GPS wants to separate into two distinct entities is very straight forward. That is, Old Navy has become the real company behind the Gap name. In fact, Old Navy now accounts for more total revenue than Gap Brand and has much healthier growth than either Gap Brand or Banana Republic. Banana Republic has comps that have ranged between +2% and -10% since 2014 as the brand has gone from 18% of total sales to closer to 14%. Similarly, Gap Brand has seen comps decline has much as -6% over the same period while shrinking from 40% of total sales in 2014 to less than 33%. Conversely, Old Navy has maintained robust growth has the brand has not seen negative comps since 2014 and has grown from 38% of total sales to approximately 45%.

Additionally, the Company for the first time disclosed segment-specific operating margins at an investor conference hosted by Goldman Sachs in 2016. Management reported operating margins for each brand as:

- Old Navy: 14%

- Athleta: 11%

- Banana Republic: 8%

- Gap Brand: 2%

Which brings us to the consolidated EBIT margins of ~11%. This definitely looks like it confirms the narrative that Gap brand is dead or in the process of a very slow death and Old Navy continues to maintain a healthy financial position.

Aside from Old Navy maintaining healthier comps and achieving robust growth, another reason why this spin makes so much sense is cannibalization. This is a concept I’ve rarely seen talked about in the media, other write-ups, or the company itself. In the same investor day I referenced above, management declared they were pursuing a new strategy: to rationalize their specialty fleet and grow Old Navy, Athleta, and their Factory stores. Their factory stores are essentially off-price value stores of the Gap Brand and Banana Republic brand. This strategy makes sense on the surface because consumers in general have been fleeing specialty stores in favor of value stores – so it makes sense that the factory stores have been outperforming. But as soon as you turn Gap Brand into just another value store then I’m not sure how consumers are supposed to differentiate between Gap and Old Navy. To me, this was management admitting that Gap and Banana are in essence, dead. Which makes all the more sense why the company is spinning them off.

A preliminary valuation of Old Navy makes Gap Inc. appear to offer compelling value. Old Navy did $7.9 billion in total revenue in 2018. So if we take the disclosed operating margins of 14% then we can infer the Old Navy segment did approximately $1.1 billion in operating profit. Ross is probably the most comparable company to Old Navy. They trade at around 15x operating earnings. If we use a very conservative 10x multiple of operating earnings then that would imply Old Navy alone is worth more than the entire current market cap (which is about $9 billion). Is the market really attributing negative value to Gap’s remaining portfolio of brands? Let’s have a closer look.

The Company

Gap was founded by Donald and Doris Fisher in the 60s. Their business model was reselling Levi jeans and aimed at attracting the younger demographic. They were able to grow the store to $2 million by 1970 and eventually stopped selling Levi’s jeans and started making and selling clothes themselves. Gap went on to go public by 1976 and acquired Banana Republic in 1987, launched Old Navy in 1994, and acquired Athleta in 2008.

Gap Inc. is an omni-channel apparel, meaning it derives business from Company-operated stores, franchise stores, and through online sales from its portfolio of 5 brands. Gap Inc. reports over 3,100 Company-operated store locations and 472 franchisee operated stores. GPS operates in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Ireland, Japan, Italy, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Mexico.

Here’s a brief description of each brand:

Old Navy Global. Old Navy was founded in 1994 to serve as a value brand to Gap Inc.’s customers. Since its launch, Old Navy Company-operated stores have expanded into Canada, China, and Mexico, while franchise stores operate in eight other countries. Competing against brands like Fast Retailing, H&M, and Ross, Old Navy focuses on what they call ‘fashion essentials’ for the whole family. By any estimation, this was management attempting to capture customers in the value market. As Old Navy has over 1154 stores and represents 45% of consolidated revenue, it has morphed into Gap Inc.’s flagship brand.

Gap Global. Gap Brand maintains 1,242 company owned stores, and contributed 30% of 2018 consolidated revenue. Gap has been able to grow through the years as it launched the collections: GapKids, babyGap, GapMaternity, GapBody, and GapFit. Gap Global is, quite obviously, the primary legacy brand.

Banana Republic Global. Founded in 1978, Gap acquired the brand in 1983 and changed it into an upscale apparel brand. Banana Republic currently represents ~14% of total revenue and company-operated stores stand at 601. Along with Gap Global, Banana Republic specialty stores are fully matured and have seen, at best, stagnating growth over the previous five years. However, Banana Republic factory stores have seen improvement in traffic and, along with Athleta, appear to be the only bright spots in the newly formed company.

Athleta. Founded in 1998 and acquired by GPS in 2008, Athleta targets the athleisure market by designing versatile performance apparel catered for active women and girls. Growing year over year from 148 store locations to 161 in FY 2018, Athleta appears to be the healthiest brand in the Newco’s portfolio.

Intermix. At 36 stores (down from 38 year-over-year) across the US and Canada, Intermix is a boutique fashion brand delivering on-trend pieces from established designers.

Where’s the Moat?

Gap Inc. certainly appears to be a market leader in the retail industry as I’m sure even the most frugal among us have shopped at one of the company’s stores in the past year. Despite the irrefutable fact that the Company maintains an almost unparalleled brand name, does the company have a moat? What would a moat look like in the retail industry and how would you even go about measuring it?

The larger question we have to tackle first is what a moat exactly is and what it isn’t. I attended an investment conference recently where a gentleman opined that the way Warren Buffett invests is dead. He went on to assert that WEB buys brand names and with the advent of the internet and Amazon, the economic viability of such enterprises are being called into question. I think this question is up for debate as you could make the argument the business (Gap) absolutely possesses a moat. It has a loyal customer base, brand value, real estate infrastructure, and so on.

However, I think such claims (GPS having a moat) are dubious – and here’s why. What does having a moat mean? We all know it means a company with a competitive advantage. And those advantages can manifest in any number of ways, but when you get down to the crux of it – having a moat is supposed to translate into valuable unit economics. It’s the ability for me to make money selling a product or providing a service and yet not have you come in and compete me out of business. Everyone knows the Gap brand. We all shop there. But if the business can’t raise the prices of its products (or lower the prices it pays) and pass on the cost increases to its customers then how valuable is that brand actually? And this is the point the gentleman I referred to earlier missed. That is, Buffett doesn’t buy brand names. He buys companies with attractive underlying economics where he can also see a barrier to competitive entry. He wants companies that make a whole lot of money and who are immune from the natural competitive forces of capitalism. So, yes, Buffett has bought brand names in the past because he viewed them as a potential source of a moat. And if that ceases to be the case he won’t anymore.

The truth is, I don’t think any retailer has a moat. It should be self-evident. Can any apparel retailer really jack up the prices of its products without you noticing? After all, what they sell is a discretionary product by any measure. If Gap is selling a sweater more than Lucky Brand then why would I possibly buy it from Gap? There could be good reasons for why I would. Maybe Gap makes the exact type of sweater I like – we all have our favorite brands. But the fact of the matter is that there is always a check on how much Gap can charge for a specific product. It’s because the retail industry is immensely competitive. And the reason the industry is so competitive is because they offer a commodity. Anyone can sell me a pair of jeans. Therefore, the degree to which Gap, or any retailer, can charge me for their product is capped.

This is amplified now that we’re in the digital age where Amazon is one click-of-the-mouse or one open-of-the-phone away. In addition to these structural headwinds that Gap Inc. faces, they also face the emergence of value brands like Fast Retailing and H&M. Once you start to truly think about the competitive forces GPS has faced, you understand my surprise regarding Gap’s impressive consolidated returns. Obviously, the lousy aspects of the retail industry are a moot point if Gap possesses excellent store and unit economics, right?

Mind the GAP: Earnings from a Third-Party Finance Company Make Operating Returns Suspect

There are a lot of ways we can try to size up this company to ascertain its company-specific economics. One method we could do is break up the company by each brand. This is obviously how management decided to do things, hence the spin off. I think there’s a strong rationale for looking the company this way, as I laid out previously. You could also look at GPS’s same store economics. By this I mean you look at sales per store, sales per square feet, or how comps have been trending. All of which are broken down nicely in the annual report and will tell you a similar story: Gap Brand and Banana are dying and Old Navy seems to be growing pretty decently.

I view Gap differently. Probably different than most. I’m not sure if that’s a great thing in this case, because Old Navy might be a perfectly good retailer that looks to be trading at 10x earnings. But I just find the way management treats a few items to be very disingenuous. You see, there are a few disclosures the company makes in its annual report that I find troubling. Let’s look at one of them –

“Old Navy, Gap, Banana Republic, and Athleta each have a private label credit card program and a co-branded credit card program through which frequent customers receive benefits. Private label and co-branded credit cards are provided by a third-party financing company, with associated revenue sharing arrangements reflected in Gap Inc. operations.”

Okay, that’s interesting – certainly not groundbreaking. They have a retail credit card, so what? If any of you have been to any one of Gap Inc.’s stores recently you know what credit card they’re talking about. The sales associates push it relentlessly. I used to work at a Banana Republic. Pushing the credit card onto customers is the only thing my managers wanted me to do. That’s because it was the only thing that they were judged on, performance-wise. Corporate management says the credit cards are part of the loyalty program and can get customers coming back to the store. All of which makes sense to me. I witness this with people I know all the time – loyalty programs work. Sometimes people I know will go shopping not because they want something but because their coupon or discount is about to expire. All of that is irrelevant to us – at least for now. What is extremely relevant is understanding the economics of the credit card arrangement. Understanding it is pertinent in order to see the company for how I measure them up. Essentially, as the sole owner of the accounts, Synchrony underwrites all credit that is issued under the Credit Card Agreement. In their 10-K, under a section titled “Credit Cards,” GPS writes the following:

“A third-party, Synchrony Financial (“Synchrony”), owns and services our private label credit card and co-branded programs. Our agreement with Synchrony provides for certain payments to be made by Synchrony to us, including a share of revenues from the performance of the credit card portfolios. The income and cash flow that we receive from Synchrony is dependent upon a number of factors, including the level of sales on private label and co-branded accounts, the level of balances carried on the accounts, payment rates on the accounts, finance charge rates and other fees on the accounts, the level of credit losses for the accounts, Synchrony’s ability to extend credit to our customers as well as the cost of customer rewards programs. All of these factors can vary based on changes in federal and state credit card, banking, and commercial protection laws.”

Okay, so Gap Inc. basically acts as the marketer of the credit card. They don’t own anything; they don’t underwrite any credit. Synchrony does all that, and then pays Gap Inc. a percentage of the profits for how that portfolio of credit performs. Additionally, and I think this is important to note, this isn’t a substitute of accounts payable or anything like that. This isn’t revenue GPS would already be getting. They get the revenue from the customer at the point of sale, because Synchrony owns and underwrites the credit. And then on top of that they get “shared revenue” from Synchrony based on how the portfolio performs.

To me, that’s an entirely different source of earnings – I don’t see how we, as analysts of the business, can treat it like anything other than that. It, fundamentally, is a transaction that is economically separate from GPS’ normal course of business. And if taken to its logical conclusion this would mean that Gap Inc. has two separate sources of income: one source of income consists of their returns from their retail operations, while another source of income is from their credit card agreement with Synchrony Financial. Furthermore, I believe in order to fully assess the true economics of Gap Inc. you must separate the sources of income because they are entirely distinct sources of earnings, even though both are reported under consolidated earnings.

What’s also interesting to me is that the fiscal 2017 10-K is the first annual report in which the Company disclosed the amount of income recognized from this agreement. They also did it this year, in the 2018 10-K. But these are the only two years that management decided to disclose the specific amount they earned from Synchrony. Gap has had a co-branded credit card like this since the 1990s.That pretty much tells us that either the percentage of operating income earned from the agreement has become increasingly significant over the past few years, or it has ballooned since 2017 making the company determine it is a material source of income. Either of these scenarios are plausible in my opinion. However, this is one example of why I find the way GPS accounts for this income to be disconcerting. Since Gap Inc. doesn’t disclose the amount of income received from the credit card agreement, I had to go looking at how competitors with similar agreements performed during the Great Financial Crisis. Specifically, I found that the, now bankrupt, Toys R Us recorded the revenue from this agreement has a separate line item and recorded the money received as income. Gap Inc. historically has treated it as a reduction to operating expenses. They made an accounting change this year to record it as revenue. Additionally, the amount of income Toys R Us received from this agreement was miniscule – far less than GPS receives. Yet, they still disclosed the amount they received. Again, nothing groundbreaking – it just strikes this analyst as peculiar.

Okay, we still have two years that Gap Inc. discloses the amount they received from Synchrony. In these two years, they state that $443 million and $412 million, respectively, were received from this revenue sharing agreement in 2018 and 2017. GPS received an additional $174 million in 2017 and $176 million in 2018 in reimbursements of loyalty program discounts. With $1,362 million in operating income and $1,003 million in net income in 2018, income attributable to GPS’s Credit Card Agreement is approximately 45% of operating income and 60% of net income. Now, by any measure, that is a material source of income. When we analyze GPS’s retail operations it becomes abundantly clear that Gap Inc.’s returns from their retail operations are severely overstated.

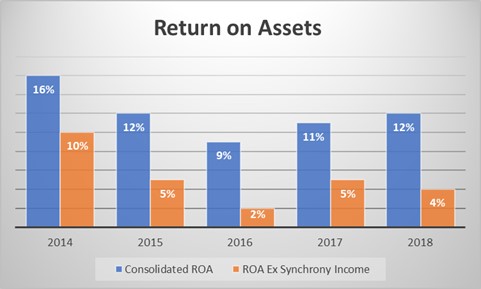

So now the question becomes, well how does GPS’s returns from retail operations perform? Here’s how:

GPS’

GPS’

Consolidated Returns Are Significantly Overstated (Note: FYs 2014-2016 are estimates)

So, things aren’t terrible. At least the retail operations aren’t hemorrhaging cash. ROE is roughly double the above figures. However, the returns are certainly overstated on the financial statements. This also complicates the task at hand because we don’t know what segment is responsible for how much of the income from the credit card agreement. Are the Old Navy margins the 14% management disclosed or are they 6%? Old Navy was about half of revenue in 2018. If we pro rata half of the income from this agreement to the Old Navy segment, then operating margins – for how I think is the best way to measure them – fall to ~8%.

As I’ve pointed out, I do think it is important to note that the agreement with Synchrony is beneficial to the company insofar as the rewards associated with the program prompt customers to return to the store. Even though the program does provide some obvious benefits to the Company, I think it’s likely that the agreement with Synchrony only serves to prop up Gap Inc.’s deteriorating underlying operations. Additionally, I think it is quite likely to be the case that this segment (the Credit Card) of Gap Inc.’s operations only serve to make a cyclical company even more so. During the past recession, consumer credit declined by more than 20% from its highs. What happens to this source of GPS’s income the next time consumer credit tightens? It certainly adds an element of risk. And we aren’t really sure of the exact criteria the company has to meet in order to receive the payouts from Synchrony. These particulars only serve to render Gap Inc.’s operating returns unintelligible, while adding an inordinate amount of risk in investing in the Company.

Further still, I find it to be very disingenuous that the first time GPS discloses any information pertaining to the amount of income attributable to the agreement with Synchrony is tucked under Note 1 to the financial statements titled “Summary of Significant Accounting Policies” (p. 47) and is recorded as a reduction to operating expenses, not as a separate line item of income in the 2017 annual report. The Company did, however, make a change to the 2018 annual report and added the agreement as a separate risk factor. Nonetheless, every other company I’ve looked at accounts for the income from similar agreements as a separate line item on the income statement as income. I haven’t seen any other company record as a reduction to expenses. And I certainly have not seen other companies where income from these types of agreements account for roughly 60% of net income. It’s this type of accounting, and this is just one man’s opinion, that I find to be a huge red flag and makes the company un-investable. Maybe I’m just overly conservative. But, in my mind, not disclosing a source of income that is this material to your consolidated returns on Item 6 of the annual report titled “Selected Financial Data” tells me that Management sees the situation exactly how I do. As the Credit Card program matures, the risk that it serves only as a temporary source of income should become clear. Since the American consumer will only be able to perpetually take on more debt for a finite amount of time, Gap Inc. appears acutely exposed if credit were to tighten yet again.

Valuation

In terms of how much Gap Inc. could potentially be worth, I think it’s only wise to attempt to value Old Navy. The brands being spun off are clearly in secular decline. Of course it’s possible that the Newco shares will face significant enough selling pressure that they become a bargain. Being a value investor at heart, I’m certainly not above buying bad businesses that are oversold, but it is important to note that the spun off company will have spectacularly horrendous economics. Safest thing to do is stay way.

So what about Old Navy? Management is currently projecting Old Navy to be a $10 billion enterprise in the next three to five years. This is completely feasible, in my estimation. The question I have is with margins. As I’ve already previously pointed out, it’s not entirely clear what Old Navy’s operating margins are from the retail operations. I think a bull, bear and base case would look like as follows:

- Bear: 7%

- Base: 10%

- Bull: 14%

So worst case scenario, if Old Navy gets to $10 billion in sales the company will be doing $700 million in EBIT. Gap Inc. trades at a total enterprise value of $9.5 billion. That means, on a worst-case scenario if you bought the stock now you’d be paying 12x operating margins for Old Navy and you’d get the Spinco for free. Certainly not a demanding valuation if you can get comfortable with income from the credit card agreement.