Kroger (NYSE:KR): A Little Too Hard

On 16 June 2017, Amazon announced a $13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods. The announcement then engendered meaningful declines in stock prices of major grocers/supermarkets, not just in the US but also in Europe. Kroger, in particular, dropped as much as 17% that day. This brings its YTD performance to -31% as of 29th June 2017.

Below, we take a brief look at Kroger to see if it is now the right time to consider an investment in it.

Introduction

Founded in 1883, Kroger is now one of the largest retailers in the world, with more than $115 billion in revenue in 2016, serving more than 8.5 million customers every day. As of January 28, 2017, Kroger operated, either directly or through its subsidiaries, 2,796 supermarkets under a variety of local banner names. 2,255 of them have pharmacies and 1,445 have fuel centers. They also offer ClickList™ and Harris Teeter ExpressLane— their personalized, order online, pick up at the store services — at 637 of the supermarkets. Approximately 48% of these supermarkets were operated in Company-owned facilities, including some Company-owned buildings on leased land.

Kroger also operates 784 convenience stores, either directly or through franchisees, 319 fine jewelry stores and an online retailer.

Several things stood out in the above description of Kroger:

- With sales of $ 115 billion, Kroger is the third biggest retail chains in the world. It is also the largest traditional supermarket chain in the US.

- Kroger’s 2,796 supermarkets are operated under a variety of local banner names.

- Fuel is a significant contributor to Kroger’s revenue, generating almost $14 billion in 2016. More than 50% of Kroger’s stores have fuel centers.

- 48% of Kroger’s supermarkets are operated in their own facilities.

We will come back to the above points below.

Durability and Moat

The durability of demand for food and groceries is very good. Most grocers do not experience significant fluctuations in real sales per square foot over time. This is especially true for a general food and grocery retailer like Kroger, whose store size is big enough for them to have room beyond providing traditional grocery to also sell items that are popular. In other words, they have more room to experiment and adapt according to the latest trends.

For example, 10 years ago natural and organic was not a central focus in their stores because it was not a central focus for customers. 5 years ago Kroger made a concerted effort to make natural and organic the “plus a little” part of their product strategy (Kroger wants their most loyal customers to say “At

Kroger, I get the products I want, plus a little”). Today, natural and organic foods are integral to their business, reaching $16 billion in annual sales in

- In fact, this makes Kroger a bigger organic food retailer than Whole Foods.

In terms of moat, supermarkets’ competitive advantage mostly stems from local economies of scale. Kroger uses a 2 to 2.5 mile radius to define its local market for each of its store. This demonstrates the small area of competition for each store.

In general, grocers usually compete on thin margins but can still make good to great returns on invested capital or equity based on high inventory or asset turnover. To attain high asset turnover, you need a big store and well-rounded product offering to attract a large number of regular customers. As a result, the location of each store is important. An area of 2 to 2.5 mile radius usually will not have multiples of such locations. This thus inherently limits the potential competition once you have an established presence in a local area. This also explains why Kroger generally uses local banner names.

For a more detailed discussion on the durability and moat of supermarkets, please read the excellent posts by Geoff here and here.

Debt and Properties

Let’s now talk about something more specific to Kroger.

On an EV/EBIT basis, despite the recent drop in stock price, Kroger is hardly cheap at 11.7x. Part of the reason is the big debt load on its balance. As of May 2017, net debt of Kroger stood at more than USD 13 billion. Against the LTM EBITDA of USD 5.3 billion, that’s a not insignificant net debt to EBITDA ratio of close to 2.5x.

The major reason for its big debt load is the uncommon strategy of running supermarkets at its own facilities. Most supermarkets lease the facilities and have little debt (i.e. favoring off-balance sheet leasing obligation instead of on-balance sheet debt) However, Kroger, as mentioned in the introduction, runs 48% of its supermarkets in its own facilities.

Looking at its balance sheet as of the end of Jan 2017, we find USD 3 billion of land at cost. Buildings, leasehold improvements and construction in progress are USD 11.6 billion, USD 9.3 billion and USD 2 billion respectively. In total, what can be considered as initial investments into supermarket facilities, ex equipment, is around USD 26 billion. Total debt is at USD 13.4 billion. Given the quality of sites of big supermarkets, it should be reasonable to expect those sites to be able to back long-term debt by 100% at market value. In fact, it won’t be surprising if the market value of Kroger’s own facilities exceeds the value of its long-term debt.

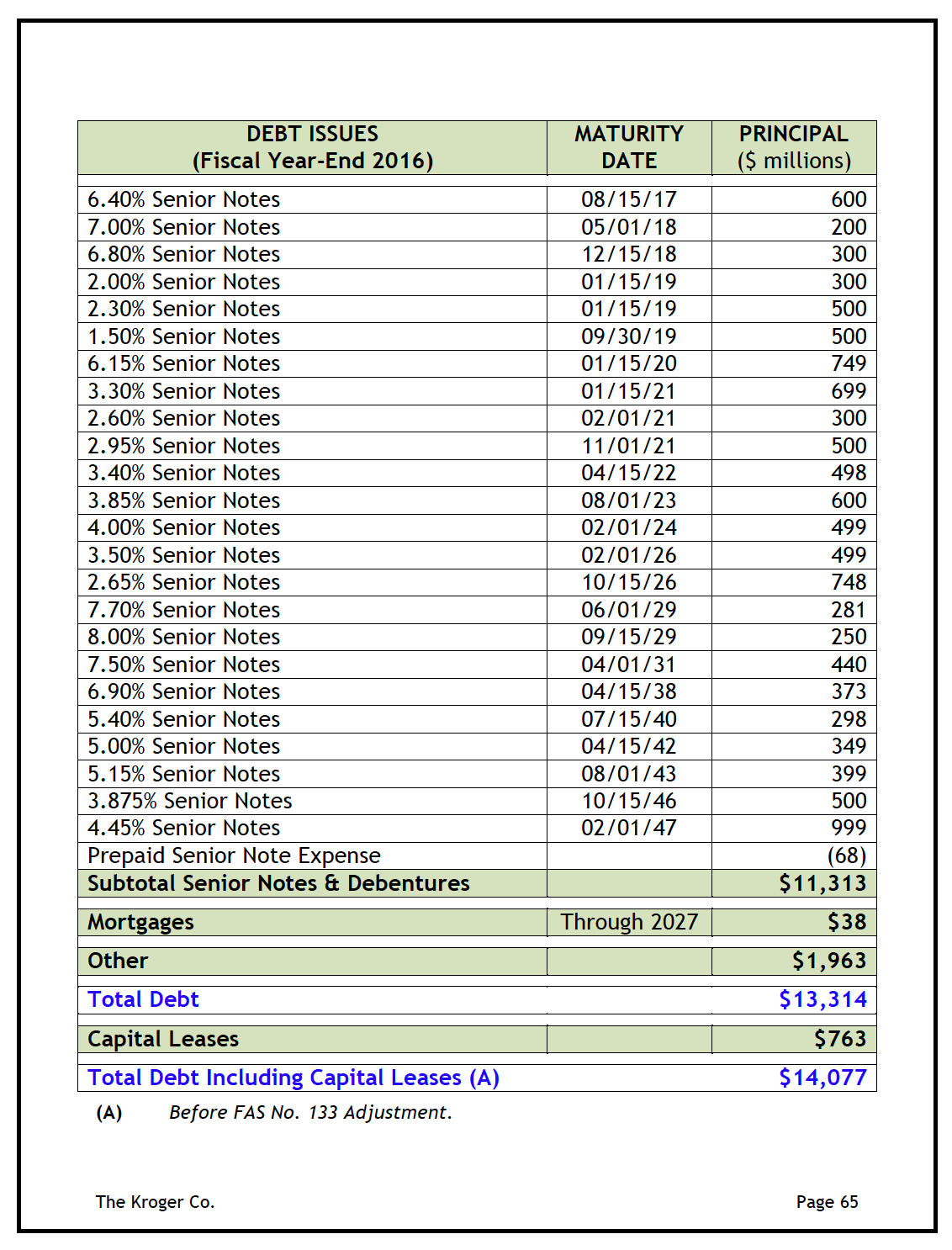

This should also explain why Kroger has been able to borrow such long-term debt at these favorable rates. The following is a detailed breakdown of Kroger’s long-term debt profile by the end of Jan 2017. Out of the USD 13.4 billion, USD 11 billion of that is long term, with favorable and fixed interest rates, ranging from 1% to 8%. Their interest payment divided by debt outstanding in FY 2016 comes out to 4.2%.

The point here is despite the optically high level of debt, for Kroger, this could very well be seen as a plus. The ability to finance a stable business that earns a decent return on capital greatly enhanced shareholders’ return. This is the main reason why Kroger’s ROE has averaged around 25% since 2000.

And if we were to compare Kroger against other grocers that lease all their facilities, we should imagine Kroger using the same strategy for an apple to apple comparison. In this case, we would need to hypothetically double Kroger’s rental expense, while taking away all of USD 13.4 billion in debt.

For the past 4 quarters, rent expense totaled USD 889 million, doubling that gives us USD 1.78 billion. This would give them a trailing 12-month operating profit of $2 billion. Without all the debt, the hypothetical enterprise value will then drop to USD 20.6 billion. The EV/EBIT becomes 10.3x.

LTM interest expense was USD 545 million. Removing interest expense and doubling the rent results in a net decrease of USD 354 million in operating profits. Assuming a 35% tax rate, net income would have been lowered by USD 230 million. As an upshot, their trailing P/E to Kroger would increase from 13.7x to 16.1x.

This demonstrates that borrowing long term has been the right strategy for them, saving them USD 230 million last year in profits.

So, is Kroger Attractive Now?

Moving back to reality, Kroger trades at an actual P/E of 13.7x now. At 13.7x earnings, this gives us an earnings yield of 7.3%.

Since FY 2006, Kroger has been aggressive in distributing cash to shareholders through both dividends and buybacks, with more emphasis on the latter. The average payout, including both dividend and buybacks, is basically 100%. (Here, I adjusted the net income for FY 2009, where a goodwill write-down happened) The reason why they have been able to grow is through leveraging up. From FY 2006 to the end of FY 2016, total debt doubled from USD 7 billion to USD 14 billion. Total debt as a percentage of equity also increased meaningfully from 1.4x to 2.1x. Throughout this same period, EBIT only increased by 50%.

Over the long term, Kroger’s goal is to achieve a net earnings per diluted share growth rate of 8% to 11%, plus a growing dividend. The current dividend yield is 2%. Therefore, if they can attain this lofty goal, the long-term total return of owning Kroger from here can be 10% to 13% p.a.

Whether you believe Kroger can really achieve this goal comes down to your answers to the following key questions:

- Is the competitive landscape going to be similar in the next 20 to 30 years as it has been in the past? i.e. Will someone like Amazon change the food/groceries industry after its acquisition of Whole Foods?

- How fast can Kroger grow going forward?

- This depends on how fast their same store sales can grow

- How fast they can grow their supermarket square footage organically in the future

- And how many acquisition opportunities they can get and at what valuations

- How much leverage can Kroger take safely?

- This then determines the likely total payout ratio (dividend yield and share buyback rate) of Kroger going forward.

Misjudgment

While we discussed briefly the durability and moat of supermarket chains, it doesn’t seem to me we got much wiser in answering the above key questions.

The question of what Amazon can do to your (retail) business always seem to loom large on the horizon these days. Granted, I believe there will always be a market for grocery shopping in physical stores. The enjoyment of going for a supermarket trip just doesn’t seem likely to ever disappear to me. (Unless virtual reality can offer the exact same experience, which even if it happens, should be years down the road). The need to be at your house at certain periods of time will remain inconvenient to most. (Unless delivery can be fully automated. Then delivery can more easily happen at night. This again could take some time).

Moreover, it is not clear how Amazon can achieve a meaningful cost advantage over large supermarket chains in the domain of food. Not only is the composition of products for each customer going to be very different, the difference among products within each purchase basket can also be huge. (i.e. some are longer lasting, while others being perishable) The handling is much more difficult than packaging the usual items Amazon deals with. And the overall purchase per visit is usually low at around USD 60 only.

The current supermarket model is also different from the fulfillment center model of Amazon. If Amazon could find a way to run its supermarkets using, say, only 200 mega stores throughout the country, where each store acts like a fulfillment center, then it’s more likely they can run a tighter operation. Still, that assumes Amazon has found a way to distribute perishables efficiently over a much longer distance, such as 30 miles.

This is not to suggest Amazon has no chance to make a dent in food. What they can do is use the existing Whole Food stores to experiment, gather more customer data, and find a way to offer customers a better shopping experience through technology, either indoor or online supported by in-store pick up.

Kroger, with its location based advantage could certainly catch up with any new trends. While Kroger is unlikely to get totally decimated, it’s not a given they can compete as well as they had in the past should any vastly different shopping experience need to be offered. Even a market share decline in the future could affect the total return of Kroger meaningfully. This brings us to the second question of growth.

Kroger’s ROE has been around 25%. To grow earnings at 8%, that requires them to reinvest only around 32% of earnings. Theoretically, they could then distribute all the rest. At 13.7x earnings, this would be a dividend yield of close to 5%. Adding that to the 8% of earnings growth, total return would be 13%.

The only problem is Kroger has found it difficult to reinvest organically. First, they already have close to 2,800 plus stores in the US. Second, unlike a Walmart or Costco, Kroger is more of a “traditional supermarket”. In areas that they don’t have a presence, such as New Jersey, there already are local players that dominate the market. In FY 2016, Kroger has only increased its store count by 65 basis points on a net basis. In FY 2015, had they not acquired stores, their store count would have decreased.

This suggests their growth in the future will mainly rely on same store sales growth and acquisitions. Management’s top range target for same store sales growth is currently 3.5%. Given their recent performance, it’s clear that goal might be a stretch, especially if this is used as a long-term goal as well. Inflation is not likely to be more than 2% to 3% for the US in the next decade or two. This means if you want to achieve 3.5% same store sales growth, you need to achieve productivity gain in your stores. Acquisitions is even more difficult to predict. What’s certain is their acquisitions, in aggregate, will not generate a 25% return on investments.

What about the reliance on debt? Over the past 12 years, Kroger has decreased its share count by a rate of 3.8% p.a. Let’s assume Kroger keeps paying out 100% of earnings in dividends and share buybacks. Then Kroger should be able to at least keep this up. Through buying back share, EPS could increase by close to 4% a year. Let’s also assume same store sales growth will be 1% for Kroger going forward. The amount of capital they need to invest to push EPS up another 3% per year, will depend on the blended return on investment from internal investments and acquisitions, on a total capital basis. This is almost impossible to estimate. Let’s be generous and say they can achieve a 10% return. Should they fully rely on borrowings to grow that much a year, their total debt will grow to USD 19.1 billion by 2027 and USD 27.5 billion by 2037. EBITDA, growing 4% a year would be USD 7.9 billion by 2027 and USD 11.7 billion by 2037. It turns out under the above assumptions, Kroger will be able to keep their leverage ratio roughly unchanged. However, what’s the likelihood they can really achieve a 10% return on their investments, especially when they need to rely more on acquisitions? At a more reasonable 5% return, total debt would grow to USD 24.8 billion by 2027 and USD 41.7 billion by 2037. The leverage would then be 3.1x and 3.6x respectively.

Conclusion and the Too-Hard Pile

I hope the above illustrates the point that without the ability to grow organically, it’s hard to get comfortable about Kroger’s ability to grow its EPS by 8% a year without more aggressive assumptions such as meaningful increase in leverage.

I am putting Kroger under the Too-Hard Pile for now.