NACCO (NC): A Contract Coal Miner with Stable Inflation Linked Profit Per Ton, a P/E of 10, a Strong Moat, and No Leverage

Overview

NACCO is primarily a services company, in the guise of a coal mining company, deriving all of its revenues from its US operations. It provides the service of managing mines and delivering raw materials – coal and limestone – to several large customers on a cost-plus basis on long term contracts. It has mines in several southern US states, HQ in Texas, and its two largest coal mines by coal volume, are in North Dakota. In the Q1 19 earnings call, it changed its reporting structure, to now report its business in three segments:

- Coal Mining (coal extraction)

- North American Mining (limestone extraction, and one sand/gravel mine just opened)

- Minerals Management (oil and gas royalties)

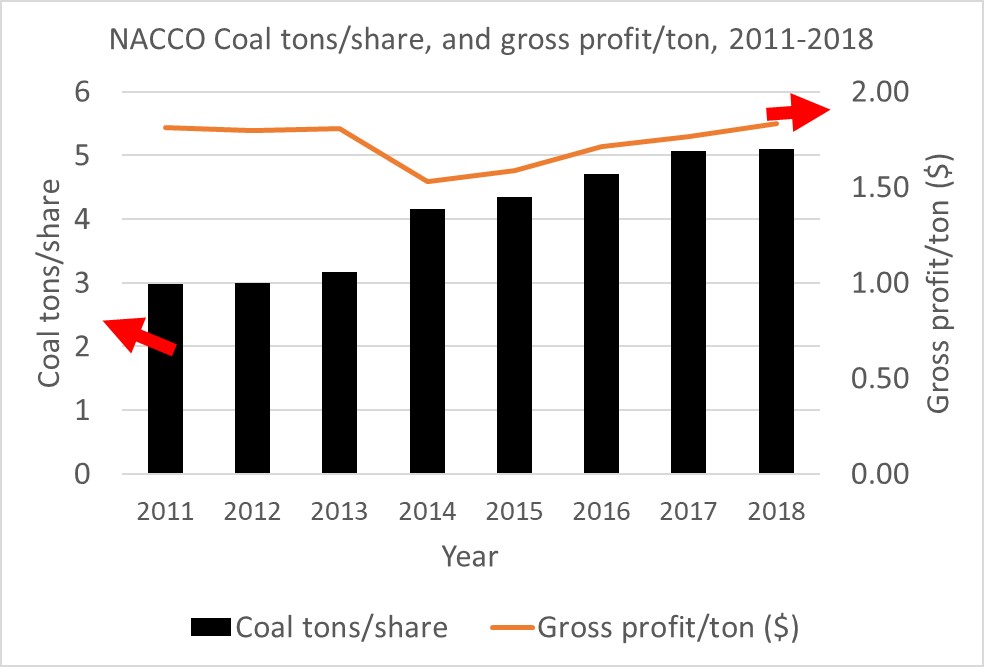

Coal and limestone/limestone are mined in two distinct ways: Consolidated mining means that NACCO owns the mine, pays all the costs, assumes the liability for reclamation, and sells the coal on the open market and so is subject to the coal spot price. There is now only one consolidated coal mine: the Mississippi Lignite Mining Company (MLMC), after the shutdown of various mines under the Centennial Natural Resources subsidiary at the end of 2015. Unconsolidated mining means that NACCO operates the mine, and is paid a fee per tonne of coal/cubic yard of limestone mined, under cost-plus, inflation-linked long term contracts. The customers assume most of the risks and the long-term obligations of operating the mines, paying for equipment, mine reclamation responsibilities, and all other costs. Therefore, NACCO is not exposed to the coal spot price or the price of limestone under these contracts. The gross profit/tonne for these mines is very stable – less than a standard deviation of 6% over the last seven years. Most of NACCO’s profits come from unconsolidated mining, and most of these from coal mining rather than limestone mining. Other coal companies may hedge their exposure to the coal spot price: instead NACCO avoids this risk by selling to the customer for an agreed profit margin. This also reduces the price variations for NACCO’s customers. The image above shows the gross profit/ton of unconsolidated coal over the last seven years, and also the tons of unconsolidated coal mined/share, which has been increasing due to an expansion in unconsolidated coal mining.

In the last seven years, an average 76% of profits came from long term contracts for mining principally coal and limestone (unconsolidated mines), 15% of its profits from royalties for oil/gas extraction on land it leases/owns, and 9% of profits from consolidated coal mines. There are various types of coal: NACCO almost exclusively mines lignite, which is the lowest quality coal, with a low energy density per ton. Therefore, it does not pay to transport it any significant distance, so coal fired power stations tend to be co-located with the lignite mines. This is the case for most of the mines that NACCO operates. Coal is mined exclusively from surface strip mines – this creates large open scars in the landscape that have to be reclaimed after mining has ceased. This might be the target of further future environmental regulations. NACCO’s customers assume this responsibility for reclaiming the unconsolidated coal mines, setting aside money each year for this, which removes significant risk from NACCO. A key factor in the bankruptcy of other coal companies has been the cost of insuring their guarantees that this reclamation would be performed. These companies, e.g. Arch Coal, typically self-guarantee that these liabilities will be covered – a process called ‘self-bonding.’ They are then required to have insurance to back these guarantees. However, as the company’s financial strength reduces, e.g. through debt, the cost of the insurance rises, which puts further pressure on their financial position, and becomes a vicious circle. Several of these companies, e.g. Peabody Coal, have therefore used the Chapter 11 bankruptcy process in the last five years to shed themselves of these liabilities. Self-bonding is particularly a problem if a mine becomes non-cost effective to operate due to the price of coal declining – then the company is left with the mine and the reclamation costs, but without an income stream to compensate for this. Therefore, this insurance can be thought of as additional leverage or risk that coal companies which are exposed to the coal spot price have, beyond that coming from normal financial leverage (debt). NACCO largely avoids this risk, since its customers assume the coal mine reclamation responsibilities – therefore if it loses a contract to operate a coal mine, then it can walk away from the coal mine without further liability beyond writing off its investment in the mine.

For this MLMC consolidated mine, NACCO assumes the risks and long-term obligations of operating and retiring the coal mine, and is exposed to the coal spot price. In 2014 and 2015, NACCO made an operating loss, partly due to the low coal spot price, which hit a multi-year low of $40-$55/ton in this time period, after peaking at $70-$80 in 2011, and also due to one-off costs associated with its closure of the Centennial consolidated coal mines. NACCO’s strategy is to reduce exposure to the coal spot price over time by gradually diversifying away from consolidated coal mining– its 2018 10-K states that, ‘Outright acquisitions of existing coal mines or mining companies with exposure to fluctuating coal commodity markets, or structures that would create significant leverage, are outside the Company’s area of focus,’ i.e. NACCO will not acquire new consolidated mines under the current management strategy.

Royalty profits are more volatile, ranging from 6% of gross profits to 29% of company gross profits in the last seven years, and they make up an average of 15% of the profits in this time period.

There is concentration risk due to large customers: about 75% of NACCO’s profits depend on relatively few large power generation customers, therefore the greatest risk to the profits is the customer deciding to close their coal using plants and terminating the service contract to provide coal. This has occurred, e.g. when the Liberty gasifier station operated by Mississippi Power closed in 2017 and led to the closure of the Liberty mine. However, deliveries commenced only a year earlier, so NACCO only ever delivered a very small amount of coal to the project.

NACCO’s top two customers account for 64% of the tons of coal mined; for coal from Falkirk and Coteau mines respectively, in North Dakota.

The customer of the Coteau (Freedom Mine) is the Dakota Coal Company, which sells the coal to three plants operated by the Basin Electric Power Cooperative, and the customer of Falkirk mine is The Coal Creek power station, operated by Great River Energy. In most cases, the coal mine is located adjacent or near to the power plants, so the coal can be delivered at the lowest possible costs. Great River Energy has a plan showing that coal will remain part of their mix until at least 2030 in the same proportion as 2017 – but their 10 year plan says that any new generation will come from renewables, or other non-fossil fuel sources, so coal demand will not increase in the future from this customer (unless their capacity factor increases, i.e. the percentage of time the coal plant is operational in any given time period). The Basin Electric Power Company asked Coteau Mine to reduce its costs, which it was able to do by increasing use of draglines, thus reducing smaller vehicle movements, and using waste heat to improve the thermal value of the lignite produced by drying it prior to use- the ‘dryfining,’ process. They have a close working relationship to reduce costs. Basin Electric Power company reduced staffing at the coal power plant by 12% in 2018 to save money, and state that although this will reduce baseload availability of their coal plants, this can be compensated for by being part of the Southwest Power Pool, which gives a better ability to buy power on the market if necessary to meet demand. Therefore, the two largest customers have no current plans to close their coal plants. However they both have a stated strategy of reducing their carbon emissions over time, and diversifying into renewables – so the amount of coal purchased may not increase over time from these customers.

The current contracts for the Falkirk mine runs until 2045, and the, ‘Coteau agreement,’ was originally set to expire in 2007, but is renewable for six 5 year periods until 2037 (source: NACCO 1999 10-K), therefore the next renewal date is 2022. The terms of this latter agreement were also changed for reimbursement of actual costs, to reimbursement of a fixed amount per ton for general and administrative costs, when the agreement was restated in 2007. Therefore, this transfer some risk onto NACCO and gives them another incentive to carefully control costs.

DURABILITY

NACCO is durable only as long as demand for the coal it is producing continues, it can continue to replace any mining contracts lost, and it continues with the current strategy of avoiding consolidated coal mining.

Limestone contributes a smaller percentage of profits compared to coal mining. Royalty income from oil and gas produced on its properties fluctuates considerably – 43% variation over the last seven years. Therefore royalty income will not ensure alone the long-term durability of NACCO.

Coal consumption for electricity production has declined in the US significantly in the last decade, halving from 2008-2018, according to the US Annual Energy Outlook report, from the Energy Information Administration. In this period, there have also been about 45 GW of coal generating capacity closures, which have been replaced by oil and gas, solar and wind capacity. In the last four years specifically, the majority of added capacity has been solar and wind. A significant number of further coal power station closures are predicted in the next ten years, but the share of electricity produced from coal is not expected to fall significantly further in the next decade. Furthermore, there are no new coal power stations expected at any point in the future, so in order for NACCO to maintain or grow its coal mining business, it must take market share from other coal producers. NACCO makes up a very small part of the US coal market: 38.5 million tons of the 755 million tons mined in 2018 = 5%. It has taken share from competitors – the Bisti unconsolidated coal mine was an existing mine taken over from another company in 2017, which in 2018 produced 3.4M tons or about 10% of NACCO’s coal production.

The stability of NACCO’s margins on unconsolidated coal mined is very good – less than 6% variation over the last seven years. Margin variation comes from consolidated coal mining, and also from oil and gas royalty variation. NACCO also has an advantage over other coal producers in that it is providing a service to its customers, which is a reliable supply of fuel for power plants, at an agreed price over the cost of production. The advantage is that the customer is getting a more stable price for their coal than if they buy on the open market, which helps the economics of their power station. One customer, Basin Electric Power Co-operative (Coteau Mine) is actively engaged in working with NACCO to lower the cost of production – by optimising the use of draglines to bring coal from the mine to the power station, and reducing coal plant staffing. Due to the nature of the relationship, both NACCO and the customer are incentivised to work together to lower the cost of production – this benefits both the customer (lower cost of fuel), and NACCO (increased likelihood of customer retention, increased customer fuel usage which means higher profits). NACCO comments in its 10-K that the dispatch cost for coal fuel is the main driver of demand for the coal-fired power stations.

NACCO may be compared with another company: Westmoreland Coal which also operated a ‘mine mouth,’ model, where some of its coal production was mined adjacent to customer’s coal power plants. Westmoreland, like NACCO, focused almost exclusively on thermal coal. However, the company suffered from customers closing coal plants: the Conesville (American Electric Power Company) plant which accounted for 11% of their revenue closed in 2017, the San Juan plant which accounted for 36% of their revenue closed half its generating capacity at the end of 2017, and the Colstrip coal power plant which accounts for another 36% of their revenue, notified them in 2017 that they would shut down by the end of 2019. With $1.4 billion in debt from a series of coal mine purchases in the last decade at a time when coal prices were higher, Westmoreland coal could not meet its obligations so it filed chapter 11 bankruptcy in Oct-18. Like NACCO, Westmoreland had cost-plus contracts (Colstrip), but unlike NACCO also had contracts with a mixture of fixed price per ton, plus some variable costs (San Juan). This story highlights the main risk to NACCO – its customers deciding to close their coal plants due to competition from natural gas, renewables, or other factors. However, NACCO has been actively seeking to a) find new contract mining customers and b) diversify away from coal mining to industries with a more certain future, such as limestone mining.

QUALITY

NACCO is fundamentally more stable than its coal mining peers due to the services business model, and is diversifying into activities which should further stabilise its earnings.

NACCO’s return on capital is 23% in 2018, and 17% in 2017, where return on capital is calculated as: operating margin*asset turnover, (where operating margin is EBIT/sales, and asset turnover is sales/assets). Pre-tax return on assets = operating margin times asset turnover: (sales/assets). Before this, the net tangible assets employed in NACoal cannot be easily determined since the account for NACCO include Hamilton Beach Brands, which was spun off in Q3 2017 – NACCO was then a holding company for NACoal and Hamilton Beach Brands, whereas post spinoff it is now essentially almost entirely NACoal, and NAM (North American Mining), which mines limestone.

The EBIT margin stability of NACoal is variable, with a range of 4% to 35% over the last twenty years, with a median and mean of 16%. This excludes one year in the last ten with a negative margin of -8%, which was 2015. This was due to the closure of the consolidated Centennial coal mine mid-year, which reduced revenues significantly in that year, but reduced cost of sales less, so there was a one-off impact to income for that year. Another year with a low EBIT margin was 2016, where the coal price hit a multi-year low, which reduced earnings from the remaining consolidated coal mine, MLMC – this shows the risks of consolidated coal mining. Given that the MLMC mine contributes an average 9% to NACCO’s earnings over the last eight years, if it were to close also, this would not have a great impact on NACCO, beyond perhaps a single year dip in earnings, as happened when Centennial closed.

If the consolidated mining business is removed from the EBITDA figures, then the EBITDA for the unconsolidated mining business varies from a minimum of $45M to a maximum of $65M in the last eight years, showing that most of the variation in earnings comes from the consolidated coal mining operation. The variation coefficient in gross profits for unconsolidated coal is 6% in the last 7 years, whereas for consolidated coal it is 72%, and two of the years made a loss, when coal prices were lower. Royalties also vary significantly, but these are a smaller proportion of the profits – an average of 15% over this period.

NACCO has an advantage over other coal companies which own and operate their coal mines and are subject to spot price fluctuations – due to the cost plus service model of coal mining, it does not need to tie up large amounts of capital in the property, plant and equipment needed to run the coal mines, since the customer pays these costs and provides capital for this. Since it is able to operate with less capital, it is also less likely to need to take on debt, which reduces risk.

NACCO is fundamentally more stable than many of its competitors in the US coal industry, five of which suffered bankruptcy in the last four years:

- Peabody Energy Corp, (largest US miner) filed chapter 11 in Apr-16. Debt $10.1 billion,: (bought McArthur Coal in 2011 for $5.1 billion)

- Arch Coal (2nd largest US miner), filed chapter 11 in Jan-16. Debt: $4.5 billion, (bought International Coal Group for $3.4 billion in 2011)

- Alpha Natural Resources, filed chapter 11 Aug-15. Debt $3 billion, (bought Massey Energy in 2011 for $7.1 billion)

- Walter Energy, filed chapter 11 in Aug-15, Debt $3 billion

- Patriot Coal filed chapter 11 in Jul-12, and again in May-15, Debt $1 billion.

A common theme in these competitors is excessive leverage, in some cases from acquisitions of other coal miners when the coal price reached a peak of ~$75/ton in 2011, and decreased to a low of $40/ton in 2016, due to a combination of factors such as a slowdown in demand on the world market, competition from cheaper natural gas from US fracking, and also the cost of insuring mine reclamation costs, rising as the company’s financial position deteriorates, as previously discussed. NACCO is much more stable, since it is largely unexposed to fluctuations of the coal spot price, carries no debt, and does not assume responsibility for the reclamation of almost any of its coal mines. Furthermore, since the 2017 Hamilton Beach Brands spinoff, it has been aggressively deleveraging by paying off long term debt, so that in 2019 Q1 it has a net cash position of $67 million or $9.50 per share.

MOAT

NACCO provides a stable, long term predictable, lowest cost on the market coal fuel to its customers, and benefits from long term contracts, which give it inflation proofed, cost plus profits.

The average cost per ton of coal for the unconsolidated operations to the customer ranged from $17/ton to $21/ton over 2014-2018, calculated from unconsolidated revenues, divided by tons of unconsolidated coal severed. Note that this cost per ton does not include the long term costs of mine reclamation, and also debts owed from the subsidiaries to the parent company NACCO – but these are completely offset by the property, plant and equipment held by the subsidiaries. Coal spot prices vary across the USA, e.g. the cheapest is the Powder River Basin at $12.40/ton (2019 May spot price). At first glance, NACCO’s coal is not cost competitive with this – however, transport costs are significant, e.g. for the Powder River Basin coal, the average rail transport cost in 2011 was $16/ton, making a total of $28.40 delivered, about 30%-40% higher than NACCO’s price. NACCO’s advantage is clearly that is it situated at the mine mouth, where coal is mined adjacent to the power plants/gasifiers that it is consumed in. With NACCO’s minimal transportation costs, it is almost impossible for a competitor to undercut them. Therefore, from the power plant customer’s point of view: NACCO has four advantages as a supplier over other coal companies: 1) relatively stable fuel price as previously discussed, b) lower delivered cost than any other producer, and c) long term contract which allows a prediction of fuel costs into the future with reasonable accuracy, and d) security of supply. Therefore NACCO’s business model is a ‘win-win,’ for NACCO and its customers.

Customers would be afraid to switch to another coal provider by buying on the open market, even if the price dropped significantly, due to the volatility of the coal spot price, which would lead to their costs being unpredictable. Due to the significant transportation costs of coal, for any given power plant which NACCO has a mine-mouth supply, it effectively has a local monopoly on the supply of coal to this customer. Through the long term contracts established, NACCO also has inflation-linked cost plus increases in price, so its profits will not be eroded over time due to direct competition. The main risk is of substitution, where a fuel source other than coal is used to generate electricity.

CAPITAL ALLOCATION

NACCO’s capital allocation strategy is firstly to pursue value for shareholders by spinning off lower margin businesses, e.g. Hamilton Beach Brands in 2017, secondly to use earnings to deleverage the company so it is now in a net cash position with minimal debt, thirdly to return a minority fraction of its cash to shareholders by share buybacks, fourthly to pay dividends, and finally to retain the rest of the earnings.

Firstly, the Hamilton Beach Brands spin-off in 2017 has seen the valuation of NACCO increase from $22 per share before the spin-off to $50/share in June 2019. Hamilton Beach Brands designs and sells small electric and speciality houseware appliances, and in 2017 recorded a net income of $26M, at a net margin of 3.6%. A one-time cash dividend of $35M was also paid to NACCO prior to the spin-off.

Secondly, earnings have been used to deleverage NACCO by paying down long-term debt – since 2015 going from a net debt position of $-98M, to a net cash position of $79M in 2018. The bulk of earnings in 2017 and 2018 were used to reduce long-term debt and revolving credit agreements. The outstanding amount of these at year end 2018 is $11M.

Thirdly, capital is being returned to shareholders through an ongoing $25M share buyback programme, announced in February 2018. To date (end Q1 2019), it has repurchased 114,000 shares for an average price of $32, costing a total $3.9M.

Fourthly, NACCO has paid out just 13% ($4.6M) and 22% ($6.7M) of its net earnings as dividends in 2018 and 2017 respectively, indicating that the management sees more value in having cash on hand rather than dividends – it may be saving cash to purchase other mining contracts from other distressed coal companies, or to expand its contract mining operations for limestone (North American Mining NAM segment).

Finally, NACCO continues to accumulate retained earnings – it is not clear what management intends to do with these earnings. Given that long term debt should be fully paid off in 2019, they may make a statement as to the future strategy here.

NACCO’s founding families together control 49% of the shares, and 82% of the voting power, since they hold 35% of the class A stock which has 1 vote per share, and 98% of the class B shares, which have 10 votes per share The share repurchase programme will not increase the family control over the company significantly since they already have control, but will gradually increase the fraction of NACCO’s earnings paid out to them.

The management’s comments on their capital allocation strategy are that it is continuing to seek out expansion of its management fee model to existing coal mines, but opportunities are likely to be limited. Acquisitions of existing coal mines/mining companies are ruled out of their strategy, together with taking on any kind of debt. Expansion of royalty income is not capital intensive, so capital cannot be deployed in this way. Therefore, since the bulk of the debt is paid off, NACCO is left with two main choices: continue to increase cash balances, or else repurchase shares. Since the company is controlled by family votes, it is unlikely to significantly change its strategy, since if the family was not content with the strategy they could easily replace the board. One of the Rankin family is currently serving on the board.

VALUE

The three year average EV/EBIT multiple for NACCO of 9.5x, conceals the improvement in the multiple over the last three years – at the end of 2018, NACCO was trading at a multiple of just 5.5x, with NTA of $252M (total assets-intangibles-total liabilities), where total liabilities are $127 M. This can be compared to its competitors Peabody, Whitehaven and Alliance Resource Partners. Peabody suffered a bankruptcy in this time period, Whitehaven has a NTA of $2.5 bn, with total liabilities of just under $1 bn, and Alliance Resource Partners has a NTA (total assets-goodwill-total liabilities) of $1 bn, where total liabilities are $1.2 bn. Therefore, NACCO is most conservatively capitalised, except for Whitehaven which has a slightly lower debt:NTA ratio. The 5.5x EV/EBIT ratio for NACCO is much lower than NACCO’s 15 year average EBIT/EV ratio of 14x – however this includes a negative EBIT in 2015 – the year that the Centennial Mines closed. Even when this is excluded, there is still a 60% variation in EV/EBIT since 2011. Compared to Whitehaven Coal, the P/E ratio for NACCO at the end of 2018 was 7.2x, and for Whitehaven it was 7.6. The share price of Whitehaven tracks the spot price of Australian coal fairly well, because Whitehaven is a consolidated coal miner, so is exposed to the fluctuations in the coal spot price, unlike NACCO which is mostly not. In 2016, Whitehaven’s EV/EBIT was 91x, because the spot price of coal was low in 2016 so its earnings were low. Its 2018 production price was $43 /tonne, and thermal coal spot price in 2016 actually dropped below this for a while in 2016 (thermal coal makes up 80% of Whitehaven’s sales).

NACCO has a slightly lower effective tax rate than the current US corporate tax rate of 21% – the 2018 effective tax rate is 17.5% – primarily due to allowances due to depletion of their coal reserves. NACCO’s normal EBIT is increasing over the last three years. Taking the average $22.5 M from 2016-2018 – subtract the effective 2018 tax rate of 18%, which gives $18.5M, or $2.66 EPS, which on a multiple of 15x earnings, is $39.90/share, plus 2018 net cash of $78.9M or $11.33/share for a total of $51.23. If the 2018 EBIT of $31.1M is taken instead at an 18% tax rate, this gives $25.5M, which is $3.66 EPS, or $55/share, plus 2018 $11.33 net cash gives $66.33/share.

If the full $25M authorised share buyback proceeded at $50/share it would cancel 7.2% of the existing share capital, increasing the per-share price to $52.23/0.93 = $56.16 for the three year EBIT average 15x multiple, and 66.33/0.93 = $71.32 for the 2018 15x EBIT multiple.

It is also possible to see how the market is currently valuing NACCO: $50/share – $11.33 net cash = $38.67 per share, and with 2018 EPS of $3.66, this is a P/E of 10.6x, ($38.67/3.66 = 10.6x), or EV/EBIT of 7.8x. Therefore, NACCO seems to be trading close to other coal mining companies in terms of P/E or EV/EBIT ratios. However, for a number of reasons discussed in sections above, NACCO has much more stable earnings and is less risky than these companies, and so deserves to be re-rated to account for this. NACCO’s EV/owner earnings is comparable to Peabody Coal and Whitehaven Coal, while its EV/EBIT ratio is higher – the main difference is NACCO’s lower capital expenditure, which could be attributed to its capital-light model of unconsolidated mining, where the customer puts up the capital for the equipment used to maintain the mines.

GROWTH

NACCO is rapidly improving its earnings due to gradually increased unconsolidated coal mining, aggressive expansion of contract limestone mining, and increased royalty payments.

NACCO is seeking to grow from: taking over existing coal mining from other companies, generating more royalties for oil and gas extraction, increasing volumes in its limestone/dragline business, and selling a reclamation service for cleaning up disused coal mines.

NACCO is entirely focussed on the US; and the US coal industry is undergoing significant turmoil and change in the last 4 years: five major coal companies have declared bankruptcy – the latest being Cloud Peak Energy, on 10th May 2019. If NACCO can pick up any of the coal mines abandoned/sold by these companies, as they aim to do, then they may be able to grow. It has done this in the last few years: e.g. in 2015 production started at Camino Real, and in 2016 at Coyote Creek, and in 2017, at Bisti – the latter of which was an existing mine, which NACCO took over a contract mining role. By 2018, these three together represent 8.1M tons of coal annually, or 24% of unconsolidated coal production. The average annual increase in unconsolidated coal production since 2011 has been 6%, with growth in every year. Unconsolidated coal tons/share has increased from 2.99 tons/share in 2011 to 5.10 ton/share in 2018. The coal price in 2011 was the highest it has been during this period, showing the strength of NACCO’s business model – even while coal prices are declining, it has been growing. Indeed, as other coal companies declare bankruptcy due to coal price fluctuations and an inability to meet their mine reclamation insurance guarantees (e.g. Cloud Peak Energy), NACCO is able to grow.

Royalties for oil and gas extraction are very high margin: 61%-86% in the last five years, and are also growing, particularly in the Ohio Utica shale assets controlled by NACCO, and account for an average of 15% gross profits. NACCO expects these to increase in 2019 but does not offer guidance beyond this.

NACCO’s limestone extraction business is primarily in Florida, and it has expressed aspirations to expand beyond this – in 2019 it started a dragline operation in a sand and gravel quarry. It has added eleven new quarries since 2016, more than doubling the total number operated, and grew the unconsolidated limestone cubic yards delivered from 2000 to 5000 cubic yards from 2017 to 2018. The majority of its business is still consolidated limestone mining, but it is rapidly expanding the unconsolidated mining of limestone.

NACCO also started in the last year, a new business offering mitigation credits for habitat restoration – it remains to be seen how this business will perform. There are a lot of coal mines closing over the US, and the companies are shedding their responsibility to clean them up through bankruptcy – if NACCO can capture some of the environmental cleanup work required for these mines, then it could grow this business.

NACCO continues to diversify its earnings away from coal, and towards more predictable and stable unconsolidated mining service fee-based model. The unconsolidated mining contract fees adjust with inflation, and since their costs are paid by the customer, the effects of inflation are automatically passed on to NACCO’s customers -so their profit margins are protected from erosion by inflation, and their profits are inflation-proofed. This is valuable compared with the other coal companies, which would have higher costs in an inflationary environment, but their prices would be determined by the mineral spot price, so they would not be able to pass inflation along to their customers, as they lack pricing power since they are producing a commodity, where price is determined by supply and demand on world markets, and also mine location, since this determines transport costs to the customers.

The US Energy Information Administration’s 2019 Energy Outlook report predicts that in the next decade, average coal power plant capacity utilisation will increase from 50% to 70%, due to the closure of less efficient power plants, so that those which remain will have a higher demand. This may increase NACCO’s earnings since each customer may demand more coal for each plant, per year.

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

NACCO carries out surface mining, where a shallow, typically horizontal seam of lignite is mined by first removing the rock above, called the overburden, then the lignite is extracted. NACCO’s customers set aside money annually to reclaim the land after mining is complete by backfilling the overburden, and restoring vegetation on top. NACCO also pays for water treatment on water coming from disused mines, through the Bellaire Corporation subsidiary, in accordance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act – this is a continuing liability.

Lignite, or ‘brown coal,’ is formed when peat is compressed, and if it is buried deeper over time, and subjected to geological heat and pressure, it turns into higher quality forms of coal, such as bituminous or anthracite. It consists of 40%-60% water, therefore when it is burned, less energy is obtained per ton than other forms of coal. This means that it is not worth transporting long distances compared with other higher quality forms of coal. The energy obtained per ton of coal, can be increased by drying the coal before use, with waste, low grade heat from the power plant, and this is done at the Coal Creek Power Station in North Dakota, which uses lignite from the Falkirk mine. The customer has trademarked the name ‘Dryfining,’ for this process, which has a double benefit, allowing them to get more heat energy per ton of lignite, and also reducing greenhouse gas emissions per unit of electricity generated.

All coals contain sulfur, and heavy metals, including mercury which are emitted when they are burned, and coal fired power stations also emit nitrogen oxides (NOX). Therefore, flue gas desulphurisation, dry sorbent injection, and a variety of other technologies may be employed to reduce this, together with electrostatic precipitators to reduce particulate matter. The US has various regulations which covers emissions from power plants; some of these are listed in the Energy Information Administration annual report, namely:

- Clean Air Act amendments of 1990 (CAAA 1990) – sulphur dioxide control: acid rain cap and trade program, Phase II deadline in 2000

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx) 2003: NOx budget trading program, which includes most states east of the Mississippi

- Air toxics: Initial compliance of Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) in 2015. All power plants will have to use controls to reduce mercury emissions in the 3-4 year period subsequent to 2015, so they achieve a standard equivalent to the average of the top 12% of best controlled sources.

- Carbon dioxide: emissions controlled by state standards for renewable portfolios or regional caps on CO2.

Reductions in emissions of sulphur dioxide, NOx, mercury and air toxics are all beneficial for human health, preventing a variety of diseases.

The EPA carried out a study to look at the expected impact of the MATS regulations on the coal industry, and project less than 1% of the existing coal capacity to close as a direct result. In the last few years, the clean power plan (CPP) proposed by President Obama in 2015 is slated to be replaced by the Affordable Clean Energy act, proposed by the EPA. This is likely to require a lower level of emissions reduction than the CPP, and to give more flexibility to individual states. However, due to public concern over greenhouse gas emissions, this situation could change in the future to bring in additional controls to limit emissions, cap and trade, and encourage electricity generators to switch away from using coal. There are about 20-30 US coal fired power plants currently planned for closure in the future, and no new ones are planned to be built as of 2019, according to www.carbonbrief.org.

RISKS – POSSIBLE MISJUDGMENTS

One of the biggest areas of possible misjudgement, is whether NACCO will be able to continue to grow their coal business, which still provides the lion’s share of their profits, to be able to replace one of their big customers, if they should decide to switch away from coal as a fuel or synfuels input raw material by shutting down their plants. As discussed in the overview above, NACCO has a concentration risk in that 64% of their unconsolidated coal tons delivered in 2018 are sold to two customers, from the Coteau and Falkirk mines. This in turn is primarily influenced by the economics of using coal as a fuel compared with other technologies, such as natural gas and solar power. NACCO is one of the lowest-cost producers of coal, and the price they charge their customers is relatively stable, which makes it less likely that their customers would close their power plants, relative to other coal plants, who buy their coal on the open market. However, Westmoreland Coal which also operates a mine-mouth arrangement, did see more than one coal power plant shut down, so it is still possible. Although the US Energy Institute Administration (EIA) report predicts a relatively stable future for coal as part of the electricity generation fuel mix, they have been mistaken before when creating forecasts for the future of the coal industry. If NACCO lost their biggest customer Coteau which is 40% of their unconsolidated coal revenue, then they would need about six years of growth at the current average rate of 6% in unconsolidated coal mining, in order to fully recover this.

CONCLUSIONS

NACCO is increasing its earnings, as it increases its unconsolidated coal in tons/share from 3.00 in 2012 to 5.10 in 2018, a rate of growth of 9%/year. This does not translate exactly to EBIT growth, since 2012 was a high year for coal price (consolidated coal), and NACCO has been switching away from this to unconsolidated coal – during this period, EBIT growth was 1.5% annualised. However, the switch away from consolidated coal greatly improves the stability of earnings. Given that this period includes a multi-year low of the coal spot price, where the consolidated coal operation actually lost money, and one of the consolidated coal mines (Centennial) has been shut down, reducing costs without much change in consolidated coal tons produced, an EBIT growth rate of ~5% in the future might be reasonable.

NACCO is chosing to retain most of its earnings- only paying out about 20% in dividends, and is allocating $25M to share buybacks, and to date has used of the to eliminate long term debt. Return on equity is ~20%, therefore NACCO could be summarised as having a 5% growth rate, a 20% return on equity, and a P/E ratio of 10.0x (at a price of $50/share). Therefore, if we take the inverse of the P/E ratio as being 10%, NACCO is able to produce a 10% yield, which will increase with inflation – since its profits are mostly inflation-proofed due to the nature of the contracts.

Since the company is family controlled, there is no driving force to pay out the earnings in dividends, and past history suggests that capital will be allocated to stock buybacks.

Furthermore, NACCO is currently valued (Jun-19) at 7.5x owner earnings, or a P/E of 10.0x, similar to two other large coal companies – Peabody and Whitehaven Coal, however, it should be valued more highly than this, due to the higher stability of its earnings. About 15,000 shares are traded daily on average over the last 90 days, which is 56% of the shares outstanding, per year, so the stock is quite liquid. If it is valued at 15x earnings, the $25M share buyback is completed, and the net cash is taken into account, a valuation of $71.32 for the shares is obtained.

APPRAISAL

Business value & fair multiple: NACCO’s business value is $338 million, owner earnings 3 year average is $22.5M – range from $13M in 2016 to $31M in 2018. A fair multiple is 15x, since NACCO has a strong moat, and inflation-proofed profits. $22.5M * 15 = $338M, and so NACCO’s share value is ~$64, since the business value is $337M, with cash is $79M at year end 2018. This gives an equity value of $416M, and after share buyback there will be 6.46M shares outstanding, for ~$64 per share.

Margin of safety: NACCO’s stock has a 26% margin of safety, at current price of $50/share. The business value is $337M, the enterprise value is $251M, which gives a discount of $86M ($337M-$251M), and a margin of safety of 26% ($86M/$337M).

About the author

Dr Stephen Gamble enjoys investing, analysing and writing in depth about stocks, learning about business models, and finding out how industries work. He is also a PhD qualified chemist, who is currently working for a multinational company. He specialises in mapping intellectual property, identifying and developing new technologies and prototypes for respiratory protection products, and improving manufacturing processes. Prior to this, he did R&D in the fields of energy storage and developing new ceramic materials for fuel cells running on biogas.