Value Trading – Does It Ever Make Sense?

Article by DAVE ROTTMAN

I would like to discuss and elicit feedback from our community on the topic of value trading. What I mean by value trading is the purchase and sale of stocks in a shorter time frame than traditional long-term investing, where the buy and sell decisions are driven by the exact same fundamental analysis, margin of safety standards, and owner’s mentality that traditional long-term value investors utilize. In other words, I would like to discuss the idea of a business-oriented investment strategy coupled with the willingness for a short investment holding period in certain situations.

Theory

To start, I will simplify the investment landscape by categorizing all stocks into two buckets: slow growers and compounders. Slow growers are businesses where the intrinsic value does not grow especially rapidly, and compounders are businesses where the intrinsic value does grow rapidly. All things equal, purchased at an equivalent price to value (P/V) ratio, compounders should outperform slow growers over long holding periods. This makes intuitive sense, because a large portion of the return in investing in slow growers is the narrowing of the P/V gap, whereas the large portion of the return in investing in compounders is the value itself actually increasing. This is what Charlie Munger is getting at when he said:

“Over the long term it’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business that underlies it earns. If a business earns 6% on capital over forty years, you’re not going to make much different than 6% return, even if you buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital, you’ll end up with one hell of a return long term, even if you pay an expensive looking price.”

With that in mind, all things equal it makes sense that an investor would prefer the P/V gap to close as quickly as possible for slow growers more so than for compounders. Further, an investor who is open value trading would be more likely to trim or sell investment in slow growers rather than compounders, because with compounders there is a higher risk of selling too early, not getting back in, and missing out on the value creation that occurs for years to come.

This brings me to the practical considerations of value trading. If, as value investors, we buy businesses whose shares are available at large discounts to intrinsic value, and those shares subsequently rise quickly in price, should we hold onto those shares until the gap narrows further, or should we consider selling (at least some of the investment) and reallocating the capital to other attractive businesses with a larger price-value gap, assuming we can find such businesses? Do long-term buy and hold investors at times hurt their returns by simply holding stocks that bounce up and down, with the P/V gap narrowing and widening over time, even as the value may march steadily upwards?

I suggest that in some situation we should be willing to sell our investments in a short time period – even as short as a few weeks or months – if the P/V gap materially closes, and assuming we have other investment options that are equally qualitatively attractive that are available at a wider P/V gap. I believe this sentiment is somewhat reflected by the following quote from Warren Buffett’s 1961 partnership letter:

“Over the years our timing of purchases has been considerably better than our timing of sales. We do not go into these generals with the idea of getting the last nickel, but are usually quite content selling out at some intermediate level between our purchase price and what we regard as fair value to a private owner.”

Implicit in Buffett’s quote is that he had other opportunities that were more attractive than those he was selling. So, even if he bought a given stock at a P/V of 60, if it went up to 80, he only had 25% upside left, whereas if saw another stock at 60, that stock had upside of 67%.

Similarly, if we bought a stock at 50% of value, and it increased to 75% after one year, we are sitting on a 50% gain. If we were hoping to sell it at 100% after 5 years, that would be a respectable 15% annualized return. But, from 75%, we are only looking at a 7.5% annualized return going forward over the next 4 years. Does it make sense to hold in this situation, if there is something else trading cheaper? Would we dampen our returns by holding in this situation and not taking advantage of upside volatility?

This speaks to the idea that, as investors, we should be invested in those companies that we understand, meet our qualitative standards, and offer the largest discount to intrinsic value. Taken to the aggregate, our portfolios should be positioned similarly, and it may make sense for us to reallocate some, if not all, of our capital to those businesses whose shares are available at the cheapest price.

A Case Study and the Implications

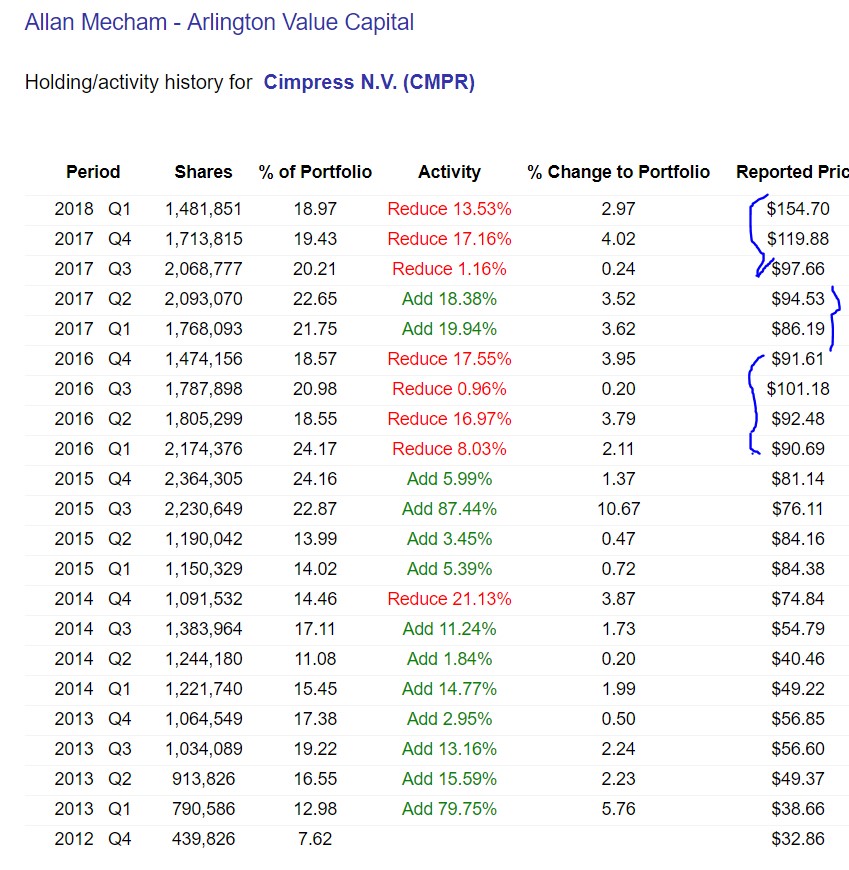

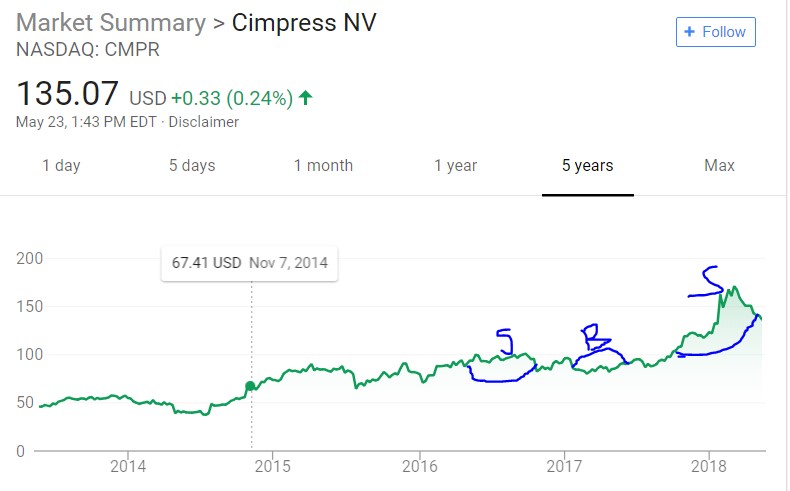

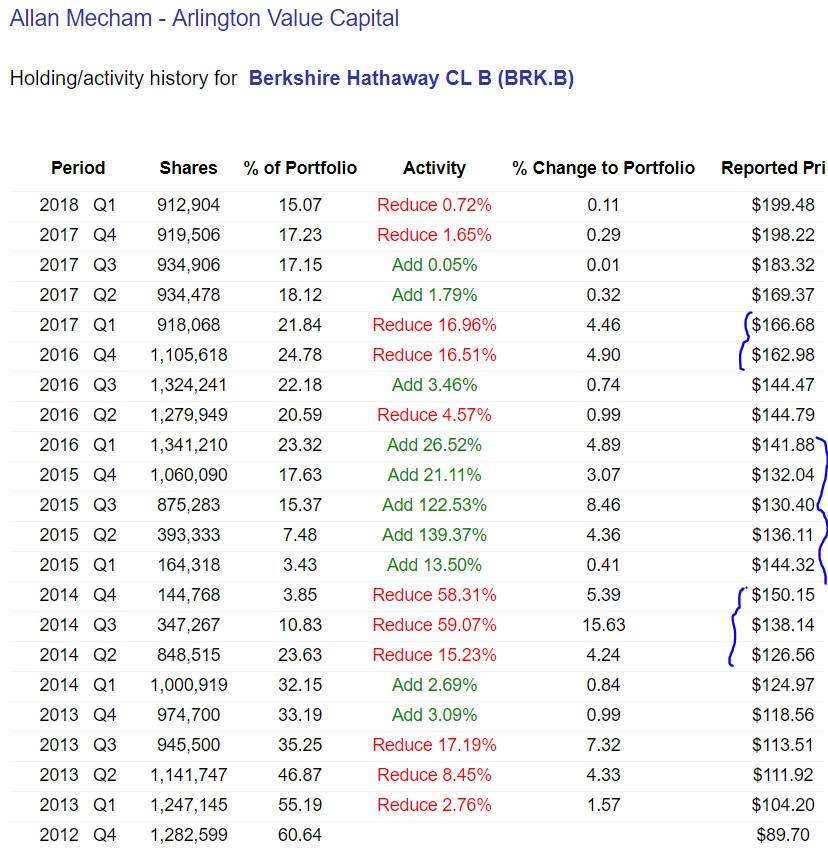

One of the reasons this topic came to my mind is because Allan Mecham’s returns have confused some investors because his portfolio returns have outperformed his biggest holdings. How is this possible? Well, there are a few reasons why, but I believe one of the reasons may be due to the fact that he strategically trims and adds to his biggest positions as the stock prices rise and fall. This is perhaps most clear in his Berkshire and Cimpress investments over the last 5-10 years. Here are snapshots of his investment activity in Dataroma of these two investments:

Cimpress:

Berkshire:

Regarding Berkshire, if we go back and check the price to book ratio, a proxy for value, we see that Mecham has added heavily to the positions when that ratio was at its lowest (<1.35) and trimmed the position as it increased (~1.45-1.65).

As of now, these buys and sells have added value. It is important to note that these have been long-term holdings for Mecham. He is not selling 100% of the position when it runs up, but he is presumably reallocating it to other securities that he perceives as cheaper. He is staying in these businesses for long periods of time, but he is reducing or increasing the position size based off the extent of the P/V gap. This, I believe, has allowed him to outperform the underlying security’s results over annual and multi-year periods. Investors frequently see their investments’ quoted prices at year-end lower than prices they reached earlier in the year. Mecham, it seems, is sometimes able to take the long-term owner’s mentality while also taking advantage of short-term volatility to outperform what a simple buy and hold investor would be able to do.

Further, I believe that Mecham is extremely skilled at rebalancing his portfolio to put the most weight on those securities trading at the largest gap to their intrinsic value. Andrew has mentioned that Mecham has owned several of the same companies many times over the years. This is true, and you could make an argument that an investor could make a career out of owning just a few securities by taking advantage of the extreme price volatility in the markets, focusing strictly on those investments he or she understands very well and buying them when the price is much lower than value, and selling when price approaches value. You could do this over and over again, and if you are accurate in your assessment of value, and the market periodically offers these companies at prices well below value, you could do quite well. This strategy, in its extreme version, would be one of following a group of well-understood securities, buying them, and then taking advantage of the differences in the magnitude of the P/V gaps of various companies’ stocks over periods of time, with reallocations to those companies whose P/V gaps widened away from those companies whose P/V gaps narrowed. Someone practicing this approach would opportunistically rebalance with the goal of maintaining a portfolio with the lowest P/V gap, and if skillful at doing so could outperform the price of the actual stocks during the holding period.

Challenges

While I believe what I have said above makes sense, I think the actual implementation of this approach is not easy. This is because there are real challenges with this strategy.

First, you have to be able to value businesses with some precision to determine the P/V gap. As we all know, business valuation is not a precise art, so even a 15% difference in the P/V gap could easily be incorrect due to misjudgment, miscalculation, etc. This could lead you to sell an investment and move it to another investment that is actually at a higher P/V value gap or worse qualitatively, leading to worse results.

The second major issue is finding securities in businesses that you adequately understand, are satisfied with the qualitative characteristics, and whose shares are cheap enough. This is one the biggest challenges in my opinion, as I simply do not believe I can at all times find an endless supply of companies I would be willing to invest in at cheap prices, and there is no reason to sell a stock at a discount to value unless you have something else cheaper to buy.

Third, this strategy is much more effective in the shelter of a retirement account. In a taxable account, the strategy would have to generate enough outsized return to overcome the tax drag. For individual investors with meaningful capital in retirement accounts, this is more realistic.

Finally, there is a risk of an investor losing their long-term orientation with this strategy. This is a real challenge to the strategy, because what I am proposing is for an investor to straddle both approaches: be willing to buy and hold long-term when it makes sense, but also be willing to take advantage of extreme upwards price volatility in certain situations. It could be difficult psychologically to dance back and forth between the two approaches. I see two specific risks related to losing a long-term orientation. First, the integrity of business valuation is built on long-term perspective, and losing that may lead one to incorrect valuations built on short-term factors. Second, even an investor fully executing a value trading strategy should be willing to hold for the long term when the P/V gap continues to stay wide. A short-term oriented investor may get frustrated and sell instead of maintaining their edge of a long-term perspective.

Examples

I would like to ground this discussion in five personal examples to bring it to life. As I am discussing the topic of value trading, I will focus my discussion on at what price did I buy a stock, what did I think it was worth when I bought it, how much it went up and how quickly, when/if I sold and how much I thought it was worth when I sold it, what would have worked better, and the implications. I will share a few situations where I was successful with shorter-term investing and a few situations where I would have been better served implementing value trading. I will not go into the actual fundamental research I did on these businesses in order to keep this discussion on the topic of value trading.

MSC Industrial (MSM)

I bought MSM in November 2015 at $60 per share. At the time, I valued the business at $110 (P/V of 55%). I considered MSM a relatively slow growing business with a decent dividend payout that offered a strong return for long-term investors at $60 per share. After less than half a year, the price had climbed to $75. Then, it stayed flat for a good portion of 2016. In October 2016, around the election time, the stock began a rapid ascent, hitting $105 in February 2017. As time went on, I began to appreciate MSM’s business more and more, and adjusted my valuation to $130. However, at $105 it was now trading at a P/V of 81%. More importantly, I came across another stock I thought was even cheaper, AutoNation. Therefore, I sold 75% of my investment in MSM at $104 – I got very lucky and caught it near the top. Shortly after this, MSM reported results and the market was disappointed with sales growth and margins. MSM dropped from $105 all the way down to $67 in mid-2017. I bought more shares throughout the year, but was a little quick in getting back in. My average basis was $80 on this second set of purchases. Finally, in December 2017, I sold all of my remaining shares in MSM at around $90, or 70% of value, to reallocate to a cheaper stock. On the first purchase, my weighted-average return was 70% over a weighted-average holding period of 1.5 years. On the second purchase, my weighted-average return was 14% over a weighted-average holding period of 6 months.

Overall, my experience with MSM was formative in my appreciation for the potential benefits of value trading, as I earned very strong returns that vastly outstripped the returns I would have gained by simply buying and holding this slow-grower that is still trading around my final sales price half a year ago. I could have a bit more a bit more disciplined on buying into MSM as it fell in 2017 (my first purchase was at $95 and my last was at $67), so discipline is one takeaway in buying back into a stock you have sold – if it was that low to begin with, it can get there again. But, the big picture for me was continuing to hold MSM at $104 or even $90 was extremely unlikely to generate above-average returns going forward, so it made sense to reallocate to a cheaper stock that I liked just as much.

AutoNation (AN)

I first bought AN in February around $48 per share and then continued to add to it as the year went on as the stock fell to a low of $39, ending up with an average basis of $44. At the time, I valued the business around $70 (P/V of 63% on average basis). Since my purchase, I have not changed my assessment of the business or its future much, but since then it has become a bit more valuable on a per-share basis due to a large stock buyback in late 2017. In late 2017, the stock began to climb rapidly, reaching $52 per share at the end of the year, and briefly hitting $62 in February 2007. Since then, it fell all the way to $42 briefly, I bought more shares, and now it is back to $46.

I have not sold any shares, but in retrospect I think I should have sold them in the high $50s or low $60s. At $60 per share, AN was around 80% of value, and I certainly had other companies I liked at much lower P/V ratios. AN was still somewhat cheap at 80% of value, but its upside was limited compared to other businesses I liked, especially considering it is a slow grower whose value is not rapidly compounding. So, I am roughly back to where I started, and although I am not concerned about my investment in AN, I would have been better served selling some or all of it around $60.

Berkshire Hathaway (BRKB)

I bought BRKB in May 2016 at $162 per share, or 1.36 times book value. Without spending a lot of time on why, I thought 1.35x book represented about 85% of value. This is not a large margin of safety, but for a business that I feel is so strong, I made an exception to my normal quantitative margin of safety requirements. As 2017 progressed, BRK’s book value steadily marched forward at expected rates, but its price vastly outpaced its book value growth. In December 2017, I sold BRK for $196, which was a 21% return over a 7 month holding period. At the time of sale, the business was trading at a price to book ratio of 1.57, approximately my estimate of intrinsic value.

This experience with BRKB was also foundational in my understanding that value trading may have some potential. It was clear to me that at $196 BRKB offered investors decent long-term returns, but certainly not as high as other stocks I was looking at. Further, while I gained 21% in 7 months, there was absolutely no way that would continue for any length of time, and in fact my compound annual growth rate was sure to go down the longer I held it. Better to reallocate the capital to a stock that had better prospective returns.

Monro (MNRO)

I first bought MNRO in August 2017 at $44 per share. I valued MNRO at $72, so the P/V was 61%. Not even two months later, it hit $57, a P/V or 79%. A month later, the stock was down to $47, and I doubled my position. Two months later, it hit $64 per share, or 89% of value. A month later, it was at $50. In my estimation, nothing of significance had happened with the business that justified the erratic price movements. In March, I sold 100% of my investment around $53.50 (P/V of 74%), for a 16% return over a weighted-average holding period of 5 months. I sold it because there were several other stocks that I liked that were trading at lower P/V ratios, including NACCO industries (NC), which I rolled the proceeds into.

While I am not unhappy with my return in MNRO, it could have been much higher if I had sold it earlier, and on both the occasions where the stock increased sharply – October and January – I gave it a lot of thought. MNRO is a great business that is growing at a decent clip, but I knew that at $57-64 it did not offer the same attractive return it did around $45. But, I held it because the P/V gap was still somewhat wide. I suppose I was afraid to leave more return on the table, but honestly, since MNRO is not a rapid grower, it was unlikely that I was going to miss out on a huge return at $64. Everything is always clearer in retrospect, but I honestly think at 89% of value I knew that there were more attractive opportunities available. Unfortunately, I dragged my feet and realized a significantly smaller return than I otherwise could have.

NACCO Industries (NC)

I bought NC at the end of March at $33.75 when it very briefly touched on the levels Geoff bought it at. I value NC at $70, so this represents a P/V of 48%. I should mention that although my quantitative valuation indicated a huge margin of safety, it is very difficult to assess how long NC’s customers’ power plants will continue to operate, so I had less faith in my valuation than I generally do. However, it was undeniably cheap.

Three weeks lately, the stock hit $39.15 and I sold it for a 16% return over three weeks. This sale was at 56% of value. This was a very unusual investment for me for several reasons: it was the shortest investment I ever made, I sold it at a deep discount to value, and I liked the business a lot with the sole exception of coal-fired power plant closure risk. Ultimately, though, I found a stock that I was better able to wrap my head around that was trading at a deeper discount to value. Interestingly, NC has fallen almost back to the level I bought it at. If I were to buy it again, which I may, and it goes up to $39 again, I would have a 35% return, instead of a 16% return, and this would be amplified even more the higher it goes. So, I would be able to outperform the year-over-year stock performance by being willing to sell it and then rebuy it cheaper later. It is obvious the risk is that the stock never falls back, and you miss out on the gain. But that is why if you sell a stock in this situation, it should only be to reinvest it in something cheaper. I am not an advocate at all of selling a stock to “lock in” profits and then sitting on cash. But I am an advocate of reallocating capital to cheaper stocks. So, at least in this case, over this time period, the idea of value trading seems to have added extra return.

Somewhat of a side note, my experience with NC is a great example to me of the validity of Geoff’s conviction to focus on overlooked stocks. NC’s stock price has fluctuated a huge amount since the spinoff: $32 to $42 to $36 to $47 to $36 to $42 to $33 to $40 and back to $34 now. In my assessment, nothing interesting has happened with the underlying business. In my opinion, the analysts on the conference calls have asked somewhat misinformed questions and you see a stock whose price movement (volatile) is very disconnected to fundamentals (static). This creates a situation ripe for fundamental value investors – either short or long-term – to profit from the situation.

Finally, my experience with the capital that was first in MNRO and then in NC illustrates a positive outcome of a value-trading practice of holding stocks with the lowest P/V ratio. Had I left my money in MNRO, I would be sitting on a satisfactory 17% gain on my $46 basis. However, by reallocating to NC, and then selling NC, I was able to realize a 35% gain, plus a few more % of unrealized gain on what I moved proceeds from the NC sale to. While this approach is highly unlikely to add that much return on average, even a few extra percentage points annually adds up to staggering differences over a lifetime.

Conclusion

In summary, I want to make it clear that I do not think value trading is an optimal strategy for all people at all times with all of a portfolio. I’m not advocating short-term trading – the merits of long-term investing have been thoroughly discussed and are legitimate, but being opportunistic with rapid upward price volatility makes sense too, for certain investors in certain circumstances. And for investors who find themselves not optimally sticking to their intended buy and hold strategies, I think it makes sense to at least have a rational and systematic approach to shorter-term investments.

My current approach is a hybrid between long-term buy and hold and opportunistic value trading, especially for stocks of companies that are slow growers. So far this strategy has added to my returns, but I do not have a sufficiently long testing period to say whether it will over the long-term with complete confidence.

So, after considering the above, I would like to open this topic up to discussion with our community. Do you think “value trading” ever makes sense, not necessarily as a general strategy but at least situationally? In what situations? Have you had experience successfully doing this? Have you had failures doing this? What do you think are the biggest issues with value trading? Do you have other comments and remarks?