GrafTech: Contracted Cash Flows Covering 60% of the Market Cap

Recent events with increase demand for lithium-ion batteries from EVs, the steel and the graphite electrode industry, have put this company in a position to be able to sell 65% of their 5-year cumulative capacity on take-or-pay contracts, thus almost guaranteeing the company a fixed source of free cash flow 5 years into the future. I believe the supply and demand imbalance will probably we present fro the next 5 years. This report will look into why that may be the case.

GE’s are an industry consumable used to conduct electricity in a furnace, generating an electric arc (a lot of heat) to melt scrap metal to the point where it is a liquid. UHP GE are made of >95% needle coke, whereas ladle electrodes, which are used in BOF’s, are made up of 20-30% needle coke. Ladle electrodes are of lesser quality because they only need to maintain the scrap metal in a liquid, as opposed to UHP GE which actually need to melt the metal. Furthermore, UHP GE takes around 6 months to produce, despite being used up in a single 8-10hr shift. Most EAF’s use 3 electrodes.

Graphite is used because it is the only material that has the chemical properties to handle a current consistently at temperatures needed to produce steel in an EAF – thus there it cannot be replaced by another product. Even at today’s prices GE only accounts for 1-5% of the production cost of steel. This bodes well for GrafTech as customers will be far more concerned with the (1) quality of the product and (2) security of supply, rather than price. Lower quality products lead to higher rates of breakage, more production downtime and thus increases production costs.

Worldwide capacity for GE is about 850,000 MT per year. Demand for steel is

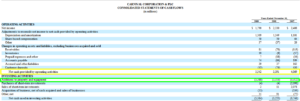

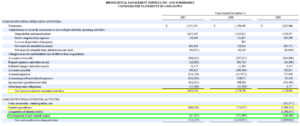

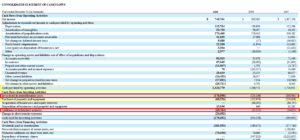

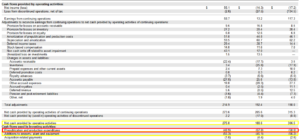

These are both publishers. And like most publishers they include a line called “prepublication and production expenditures” or “investment in prepublication cost”. Despite the fact that these expenses aren’t called “capital expenditures”, you absolutely must deduct them from operating cash flow to get your free cash flow number. In fact, these are really cash operating expenses.

These are both publishers. And like most publishers they include a line called “prepublication and production expenditures” or “investment in prepublication cost”. Despite the fact that these expenses aren’t called “capital expenditures”, you absolutely must deduct them from operating cash flow to get your free cash flow number. In fact, these are really cash operating expenses.