Time Is the Cheat Code to Wealth Generation

Here’s an inspiring story I heard the other day.

Last week, I spoke with an investor who recently inherited an investment account from their uncle. The uncle worked as a fireman, lived below his means, and invested in stocks and bonds his whole adult life. The value of the inherited investment account is $5 million.

Hearing this story brought a smile to my face. It reminded me of the remarkable story of Ronald Read, the janitor that amassed an $8 million net worth from, as Wikipedia explains, investing in dividend-producing stocks, avoiding the stocks of companies he did not understand, living frugally, and being a buy-and-hold investor in a diversified portfolio of stocks with a heavy concentration in blue chip companies.

When competing in an industry where keeping things simple isn’t sexy and outsourcing your thinking to others is the norm, it’s inspiring to hear success stories about common-sense approaches that led to extreme wealth creation for what most would consider ordinary people. (Side note: I don’t think these investors are ordinary. I think they are extraordinary.)

The investing strategies of the uncle and Ronald may have been different, but there was a similarity that nobody wants to hear.

Time.

The uncle lived to be 94 years old, and Ronald lived to be 93 years old.

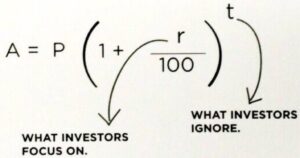

The picture below undoubtedly represents the most critical formula in finance.

Time is the cheat code to wealth creation.

Everybody knows it, but nobody wants to talk about it.

Why?

Because nobody wants to get rich slowly.

Take any amount of capital and grow it by any growth rate over 60-70 years and you’ll see the true power of compounding. Even market-type returns spit out eye-popping numbers.

Geoff and I talk about Warren Buffett on pretty much every podcast. Something we don’t mention much is that the essential ingredient to his secret sauce is time. Buffett would still be incredibly wealthy today even if he only earned market returns from the day he started investing when he was 11 years old.

Whenever I tell stories about the uncle or Ronald, someone always asks something like, “What’s the point in living below your means to invest if you’re never going to enjoy your money?”

While I understand the sentiment, it’s important to remember that these gentlemen had the independence to decide how they wanted to live their lives and what they wanted to do with their wealth. They had true freedom; and common sense got them there.

I love hearing these stories because it’s a good reminder to not miss the forest for the trees.

Keep things simple; find a strategy that makes sense to you and stick with it. Avoid anything that causes any short-term dopamine hits.

Control what you can control (i.e., your emotions, your burn rate), and avoid situations that could force you to start from “go” again, etc.

Benefit from time being on your side. Time, above all else, is the most powerful force in wealth creation.…

Read more