Why Do You Sometimes Price a Stock Off of Its Free Cash Flow Yield Plus Growth Rate Instead of Just Using its P/E Ratio?

Someone sent Geoff this email:

Written by: Vetle Forsland

Introduction

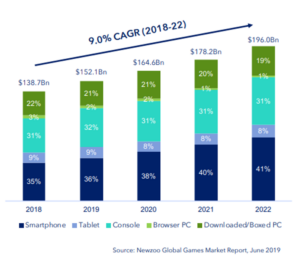

The video game industry is a large and rapidly growing market with revenues projected to reach nearly $200 billion this year, a consistent growth rate in the high single-digits, and over 2.3 billion gamers across the globe. As video games have developed in graphics, gameplay and story, while moving most of the gaming experience online, it has silently become the largest entertainment industry on the planet. According to IDG Consulting, by 2020, the video games industry will bring in more revenue globally than the music business, movie ticket sales and home entertainment combined, after an impressive 26 percent revenue jump from just two years ago. This write-up is centered around Keywords Studios (LSE:KWS), a niche leader set to benefit from all the major developments within this rapidly growing industry.

The Video Game Industry

Major video game releases put Hollywood to shame. While Avengers: Infinity War brought in $640 million globally during its opening weekend, Red Dead Redemption 2, released the same year, generated over $725 million in worldwide sales during its first three days.

The industry has gone through a big change over the past decade plus. First and foremost, the rise of online gaming, streaming and Esports turned video games from a relatively isolated experience into mass entertainment for everyone to enjoy.

For instance, the 2019 League of Legends World Championship drew 200 million viewers in 2019, more than twice that of the Super Bowl. Major players like Amazon (through its Twitch acquisition), Facebook (Oculus), Snap and Nike are entering the industry. Further, the casual mobile gaming market practically didn’t exist in the 2000s, but generated $38 billion in revenues in 2016, versus $6 billion for the console market, bringing gaming to everyone’s parents and even grandparents. Additionally, in its early history, video games were mostly a single-player activity – but the consoles of the early 2010s made online gaming the main form of gameplay, and together with streaming, turned the industry into something undeniably social.

In the years ahead, the video game market is expected to grow at a strong, consistent CAGR of 9 percent from 2019-2023. This increase is driven by the continued development of higher definition- and complexity games, next-gen consoles coming out in late 2020, and new ways of playing video games – like AR, VR, video game streaming, subscription models – as well as more sophisticated mobile games. It is in this market that Keywords Studios operates, without direct exposure to the successes or failures of individual game titles.

Keywords operates in a niche within the video game market that has grown, and will continue to grow, even faster than the overall industry – specifically the outsourced video game services “industry”, a niche set to continue to expand.

Why?

First of all, the video game industry is trending more and more towards outsourcing important tasks to third-parties, as video game developers experience increased complexity, volume and speed of content generation within competing …

Read moreFor this week’s post, I decided to talk to the camera. Be sure to watch if you haven’t here.…

Read moreTo Focused Compounding Members,

I hope everyone had a great holiday! Let me start by saying I am not one for New Year’s resolutions. I genuinely believe you should start today instead of tomorrow – and that an arbitrary date should not dictate when you should work to become the better version of yourself.

That said, one of the things I wanted Geoff and myself to do before the new year was to write down 5 goals that we would be proud of if we accomplish by this time next year. We had professional and personal goals. I decided on 5 because this was right out of Warren Buffett’s 5/25 strategy for focus. You can learn about that below from James Clear’s blog post below. (Hopefully James won’t mind me stealing his story if I link to his great book, Atomic Habits: https://www.amazon.com/Atomic-Habits-Proven-Build-Break/dp/0735211299/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1578004386&sr=8-1

/

https://jamesclear.com/buffett-focus

“The Story of Mike Flint

Mike Flint was Buffett’s personal airplane pilot for 10 years. (Flint has also flown four US Presidents, so I think we can safely say he is good at his job.) According to Flint, he was talking about his career priorities with Buffett when his boss asked the pilot to go through a 3-step exercise.

Here’s how it works…

STEP 1: Buffett started by asking Flint to write down his top 25 career goals. So, Flint took some time and wrote them down. (Note: you could also complete this exercise with goals for a shorter timeline. For example, write down the top 25 things you want to accomplish this week.)

STEP 2: Then, Buffett asked Flint to review his list and circle his top 5 goals. Again, Flint took some time, made his way through the list, and eventually decided on his 5 most important goals.

Note: If you’re following along at home, pause right now and do these first two steps before moving on to Step 3.

STEP 3: At this point, Flint had two lists. The 5 items he had circled were List A and the 20 items he had not circled were List B.

Flint confirmed that he would start working on his top 5 goals right away. And that’s when Buffett asked him about the second list, “And what about the ones you didn’t circle?”

Flint replied, “Well, the top 5 are my primary focus, but the other 20 come in a close second. They are still important so I’ll work on those intermittently as I see fit. They are not as urgent, but I still plan to give them a dedicated effort.”

To which Buffett replied, “No. You’ve got it wrong, Mike. Everything you didn’t circle just became your Avoid-At-All-Cost list. No matter what, these things get no attention from you until you’ve succeeded with your top 5.”

/

One of my goals for 2020 is to write a lot more. To quantify this, I’m committing to one post a …

Read moreHere’s an interesting article from BusinessWeek about how members of Congress do best when picking stocks from their own districts. While cynics will jump to the conclusion these representatives must be trading on inside knowledge gleaned from lobbyists, or just outright favoring local companies, I have to say I have a better record investing in New Jersey companies.

I was born and raised in New Jersey. I still live and work here. I know the place. And I do best when investing in New Jersey companies. At least half my best long-term investments were in New Jersey companies. It’s a small sample. But it’s a significant stat.

Also, I remember reading a paper in an academic journal, I’m going to say it was published sometime in the 1960s, that looked at brokerage accounts and found the two strongest predictors of good performance in any trade were the distance of the corporate headquarters from the investor’s home and the length of time the stock was held. The shorter the trade, the worse investors did. The closer the headquarters, the better investors did.

The combination of a local business held for a long time was often the investor’s best performing trade. That’s true for me. And it seems to be true for our elected representatives too.

It’s also how Phil Fisher got started investing.

Generally, it’s not a bad idea to read up on all the public companies in your home state. It might come in handy one day.

While I’m sure some folks will jump to the corruption angle, I totally disagree. There hasn’t been enough study of how familiarity affects investment performance. In my experience, familiarity turns otherwise mediocre traders into long-term value investors. Locals and insiders who otherwise aren’t value investors suddenly become very Buffett like when the business is down the street or they’re in the board room.

I’ve got a story about how being on the inside makes you a better investor.

I know a guy who used to work at Goldman Sachs (GS). Near the end of his career, he’d left Goldman and gone to work as the treasurer of a public company. It was a utility. Very easy to understand. Eventually the stock got cheap. And the dividend yield was obscene.

Now, this guy isn’t normally a good investor. He’s not terrible. He’s just not good. Not a real stock picker. Not going to dig into the 10-K of some obscure company. And definitely not a contrarian. He’ll buy some blue chips and some investment grade bonds. But he’s no value investor. And he’s no risk taker.

Day after day he sees the stock trading so low. He knows the dividend is covered. I should point out, that’s not because he’s the treasurer. This was a public company. It was a utility. Anyone could see the dividend was covered. Dividend coverage isn’t hard to calculate for a utility. Any outsider looking at the company knew the dividend was covered.

But

06/07/2012

For understanding a business rather than a corporate structure – EV/EBITDA is probably my favorite price ratio.

Why EV/EBITDA Is the Worst Price Ratio Except For All the Others

Obviously, you need to consider all other factors like how much of EBITDA actually becomes free cash flow, etc.

But I do not think reported net income is that useful. And free cash flow is complicated. At a mature business it will tell you everything you need to know. At a fast growing company, it will not tell you much of anything.

As for the idea of maintenance cap-ex – I have never felt I have any special insights into what that number is apart from what is shown in actual capital spending and depreciation expense.

When looking at something like:

I definitely do take note of the fact they trade around 8x EBITDA – and I think that is not where a really good business should trade. It’s where a run of the mill business should trade.

I guess you could get that from the P/E ratio. But when you look at very low P/E stocks – like very low P/B stocks – you’re often looking at stocks with unusually high leverage. And this distorts the P/E situation.

Which Ratio You Use Matters Most When It Disagrees With the P/E Ratio

The P/E ratio also punishes companies that don’t use leverage.

Bloomberg says J&J Snack Foods (JJSF) has a P/E ratio of 21. And an EV/EBITDA ratio of 8. Meanwhile, Campbell Soup (CPB) has a P/E of 13 and EV/EBITDA of 8. One of them has some net cash. The other has some net debt. J&J is run with about as much cash on hand as total liabilities.

They can do that because the founder is still in charge. But if Campbell Soup thinks it can run its business with debt equal to 2 times operating income – then if someone like Campbell Soup buys J&J, aren’t they going to figure they can add another $160 million in debt. And use that $110 million in cash someplace else.

And doesn’t that mean J&J is cheaper to a strategic buyer than its P/E ratio suggests.

That only deals with the “EV” part. What about the EBITDA part? Why not EBIT?

Don’t Assume Accountants See Amortization the Way You Do

The “DA” part of a company’s financial statements is usually the most suspect. It’s the most likely to disguise interesting, odd situations.

Look at Birner Dental Management Services (BDMS). The P/E is 21. Which is interesting because the dividend yield is 5.2%. That means the stock is trading at 19 times its dividend (1/0.052 = 19.23) and 21 times its earnings. In other words, the dividend per share is higher than earnings per share. Is this a one-time thing?

No. The company is always amortizing past acquisitions. So, the EV/EBITDA of 8 is probably

Recommendation: Buy

Burford Capital is complicated to value; and so vulnerable to opportunistic short sellers, but this weakness offers opportunities to long term investors.

Stephen Gamble, writer and analyst, 12th October 2019.

Stephen Gamble, writer and analyst, 12th October 2019.

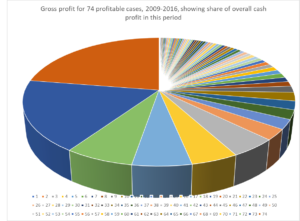

Figure Above: shows how each of 74 concluded matters in period 2009-2016 contributed to profits in this period – 4 matters make up 50% of gross profits, 11 matters make up 75% of gross profits

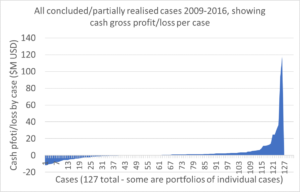

Figure Above: shows gross cash profit/loss for each of the 127 matters concluded/partially realised in period 2009-2016. 58% of cases give a positive return, the rest break even or lose money.

Burford Capital is in litigation finance, a relatively new industry in a growth phase, with complex assets. The recent attack from short sellers give rise to opportunity for longer term investors.

Lawsuits are risky for companies: they have to commit large amounts of capital up front to pay for expensive lawyers, they can take years to settle, and the return on their investment is unknown until the end, and binary: either a large cash windfall, or else a total loss, and they may even face a liability for costs of the other party. Furthermore, once litigation has started, it has to be seen through to the end in order to prevent a total loss of money invested. This often takes multiple appeals, making the total cost difficult/impossible to ascertain at the start. In summary, lawsuits can be difficult to justify to shareholders since the duration, cost and outcome are inherently uncertain. However, they are often desirable in order to protect key business interests – so the companies are left with a difficult choice when considering whether to litigate or not.

It is at this point that companies considering a lawsuit, are increasingly turning to a third party litigation finance company. They can provide capital, to avoid the problems discussed above, and in return, they take a slice of the outcome. Therefore they do not need to spend money at any point in the litigation process, e.g. on lawyers etc. since the litigation finance company will spend its money instead. This changes litigation from an uncertain and risky enterprise into a simple opportunity cost – that they might have made more money, if they had paid the lawyers themselves. It also incentivises companies to pursue litigation that they might otherwise have deemed too risky. For the company, the cost of making ~30% less money in victory or settlement, is much preferable to the risk of committing an unknown amount of money for an unknown duration, where if the commitment is not followed through to the end, all the money invested is lost. Furthermore, in many cases the company still retains some control over the litigation, and can input into the strategy pursued – without having any financial risk. Litigation finance can be crudely characterised as a ‘corporate no win, no fee,’ claims industry.

This industry is a relatively immature one compared to the personal claims one, which …

Read moreOriginally posted at www.Gannononinvesting.com on June 01, 2011

by Geoff Gannon

Someone who reads the blog sent me this email:

Dear Geoff,

in your article “Should you Buy Microsoft?” on GuruFocus, you said, that it makes sense for some investors to use LEAPS instead of the stock.

After thinking long about that, I came to the conclusion, that LEAPS can be viewed as a form of leveraged investment with an insurance against a falling stock price included…So LEAPS would make sense, if you want to leverage your portfolio with relatively low risk.

I’m not endorsing LEAPS.

I think they make sense only in situations where there is a level of catastrophic risk in the underlying stock that is not priced into the option. In general, this means low volatility stocks that nonetheless can fail catastrophically if infrequently.

Like banks.

I would use LEAPS to buy a bank because there is always the risk that a bank will go to zero. In that sense, LEAPS leverage your investment and provide protection – basically an involuntary surrender – where you cut down a huge loss while still betting on a favorable outcome.

The problem with LEAPS is that they aren’t long enough dated. 5-year LEAPS would be good. 10-Year LEAPS would be virtually indistinguishable from a stock in terms of a correct analysis resulting in profit. But 2 years is not long enough for a value investor. If Warren Buffett had bought Washington Post 2-year LEAPS instead of Washington Post stock in the 1970s he would have lost his entire investment. By buying the underlying stock, he had a return of 30% a year compounded over the first 10 years.

I’ve had stocks that didn’t work out for 2 years. But, boy, did they work out over 5 years. I would’ve lost money on the LEAPS.

Any bet that depends on the market recognizing something within 3 years is a bet where a value investor can be completely right in terms of analysis and yet lose everything simply because the clock runs out.

Value investing is largely based on being able to hold a position until the market changes its mind. I’d say it’s very unreliable to assume mean reversion in the market mood on a stock within 3 years.

The exception to this is when you’re diversifying both across a group of separate bets and across a period of time. For example, if you buy one stock a month every month and turn over the portfolio every year (by swapping out one stock each month), you may average an acceptable result because you’re actually making a dozen different bets on a dozen different stocks that depend on prices at a dozen different future moments in time.

That’s not what you’re talking about. You’re talking about making one bet on one stock that will succeed or fail based on whether or not the stock reaches a certain price fast enough.

Personally, I’m not interested in LEAPS.

And I really …

Read more